How did a dancer from South Korea master an ancient Chinese art form that has blossomed anew in modern-day America? It’s a story that can only happen in this land of opportunity.

Jimmy Cha, 41, has danced with Shen Yun Performing Arts, the world’s premier classical Chinese dance company, based in New York, since 2008. His path to performing on the world’s top stages was unexpected, but it has made him appreciate America all the more. It was here that his desire to dance was not only fulfilled, but also led to a greater purpose.

America, Where Dreams Come True

Mr. Cha grew up between South Korea and the United States due to his father’s job in the South Korean air force. Between the ages of 4 and 14, Mr. Cha spent several years living in Ohio and Indiana, where he embraced his mischievous side.

He remembers one particular trick: He would go to the local convenience store with friends and pay for items without getting a bag to carry them. Upon exiting the store, he would glance at police officers nearby, and then sprint away as if he had stolen the goods. When the cops caught up to him, he would then pull out a receipt. “I had very creative ideas to make certain people upset,” he joked.

When he returned to South Korea at age 15, he realized he didn’t fit the mold. There are established hierarchies in social relations that one must respect. For example, “you don’t speak unless you’re spoken to,” he explained. “People don’t really like to go out of the boundaries. There are a lot of unspecified rules that you have to follow.”

He felt pressured to conform to an expected trajectory for societal success. “You need to get into the top high school to get into the top college, and that’s how you get a good job,” he said. He wasn’t interested in pursuing that track.

His father suggested dance as a possible career option. Mr. Cha had already taken up music, as well as sports like gymnastics, swimming, and track and field. Dancing combined the musicality and physicality that he had learned before. He was quickly accepted into an art school and gravitated toward ballet’s systematic training. It became his “obsession,” he said.

Mr. Cha soon won national prizes for ballet. But when he applied to dance companies for performing roles, they rejected him. His height and build did not match the long, lithe physique they were looking for. “A lot of their classical ballet is very heavily Russian-influenced, and Russians care a lot about visual aesthetics,” Mr. Cha said. He felt stuck and thought about quitting dance. Meanwhile, his family pressured him to find another route that would bring him success.

That’s when Mr. Cha decided to move to California to study Eastern medicine. He returned to the United States in 2002, feeling in his gut that a path would open up for him there.

“In America, anyone can be who they want to be. That gave me hope,” he said. During his free time in between studies, he auditioned for dance companies in Southern California. He was hired as a soloist for Anaheim Ballet, and later promoted to principal dancer. Opportunities were lining up. This time, he was determined to see it through: He quit his Eastern medicine program and transferred to Point Park University in Pittsburgh to pursue a bachelor’s degree in dance.

Dancing With Purpose

After graduating from university, Mr. Cha started a master’s degree in dance at New York University. Through acquaintances, Mr. Cha heard about a burgeoning dance company, Shen Yun, that trained dancers in classical Chinese dance—a dance system with millennia of history. It was nearly lost after the Chinese Communist Party took over China and systematically destroyed elements of traditional Chinese culture. Shen Yun’s mission was to revive this lost art form.

Mr. Cha was intrigued after watching a performance in New York. He observed the differences between ballet and classical Chinese dance—akin to the differences between Western and Chinese paintings: “Western painting is very form-oriented. Every angle, every stroke has to be in such a way,” whereas Chinese painting is about expressing a feeling. He wanted to learn this art form that was like an entirely new language to him. He auditioned and joined the performing arts company in 2008.

Mr. Cha learned that classical Chinese dance intricately tells stories through movement. “Because [classical Chinese dance] hasn’t been passed down systematically, it’s always evolving. So, in terms of the level of artistry, it’s always advancing.” There were always new ways to perfect the forms through which his body could express the emotions portrayed in a piece. More importantly, he found a purpose beyond advancing his own career. “Trying to revive anything that was once lost, I think there’s huge value in it,” he said.

Performing with Shen Yun taught him humility. Depending on the piece, dancers play a lead role or a supporting role as a background dancer. “With the smaller roles, you still have to put all your heart into it. It helped me become more well-rounded and more humble,” he said. Performing wasn’t about being in the spotlight, but about achieving excellence no matter his role.

Mr. Cha is now in his 17th year with Shen Yun—with no signs of slowing down. He’s motivated by a desire to serve audiences around the world—”we want better quality every year,” he said—and to set a good example for his two young daughters. He wants to show them the value of hard work and commitment. His parents are proud of seeing what he’s accomplished after seeing him flourish; they take care of his daughters when he’s on tour with the company.

As one of the company’s oldest performers, he also wants to be a positive role model. “Everybody’s watching each other and learning from each other. I want to set a good example in terms of the work environment, to give people some sort of inspiration,” he said.

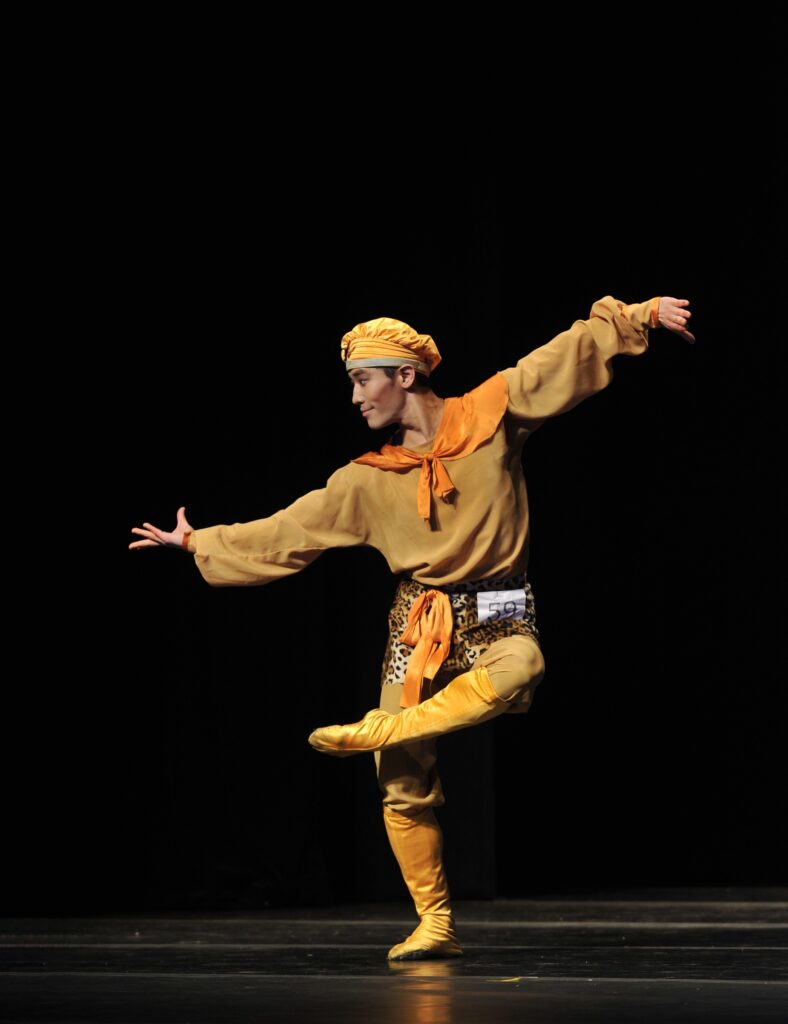

For several seasons, Mr. Cha played the Monkey King, a beloved character from “Journey to the West,” a famous 16th-century Chinese novel. His childhood gymnastics and acrobatics training made him especially well-suited for the fast, agile movements of the sometimes-mischievous character.

He also learned an important lesson from portraying the character, who encounters 81 trials while accompanying a monk on his journey to India to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures. “Only when one looks beyond oneself and maintains a steadfast heart, can one succeed,” Mr. Cha said. And in many ways, Mr. Cha’s own story reveals that he has done just that.