Irreverent Warriors is an organization that was built from the ground up to address suicide. It does not use conventional methods but instead uses laughter, shared suffering, and familiarity to fight suicide. It works with those most vulnerable to suicide: the veteran population. The Irreverent Warriors mission is “to bring veterans together using humor and camaraderie to improve mental health and prevent veteran suicide.”

Suicide is a national crisis. In 2019 alone, there were an estimated 1.38 million attempts and a total of 47,511 suicides, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Unfortunately, suicide affects active military and veterans disproportionately. When separated from the national averages, it turns out that veterans are twice as likely to commit suicide over nonveterans, according to a 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

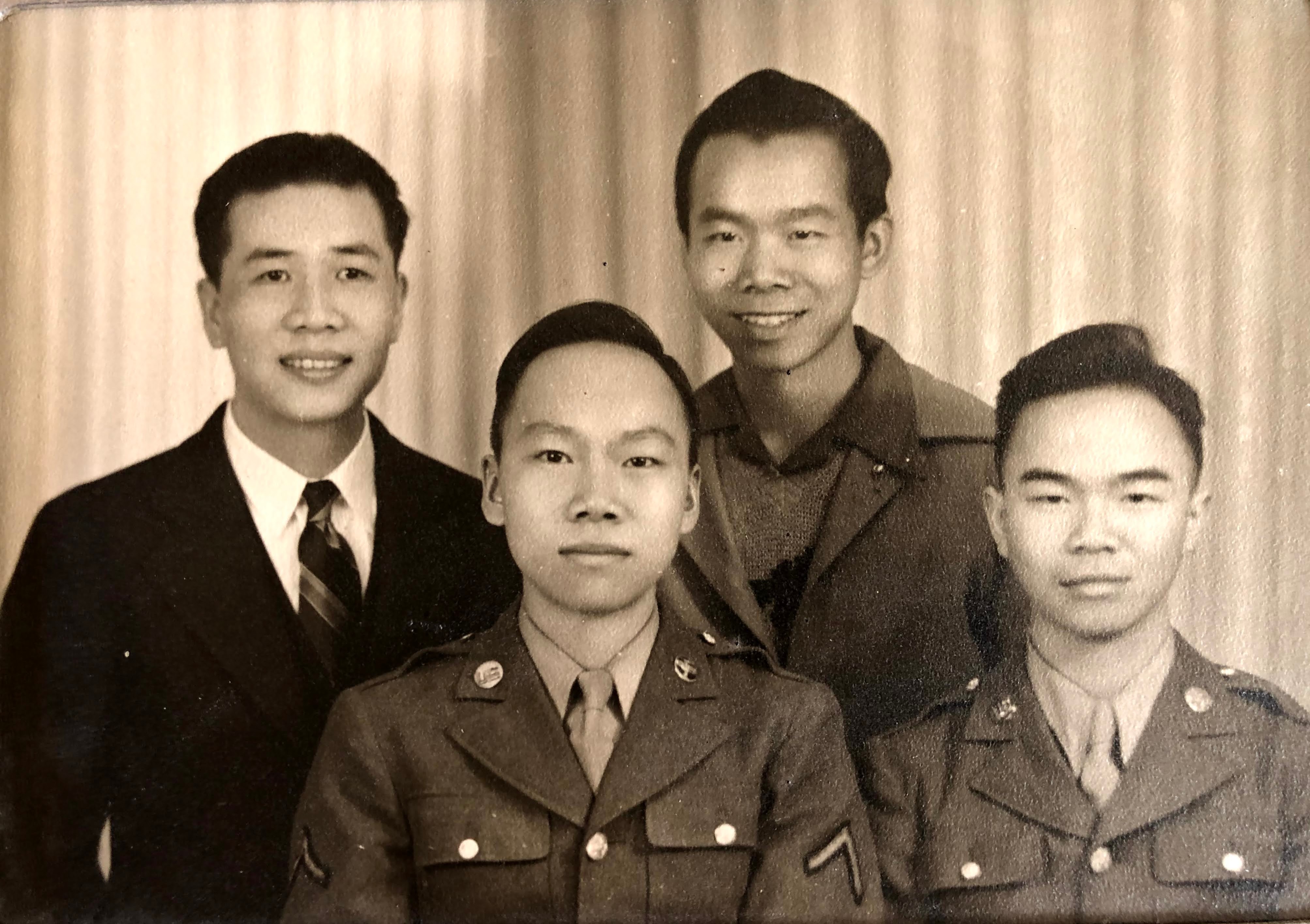

Combat-related deaths of military servicemen since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, total 7,057, according to a new report released by the Pentagon. These numbers include all deaths related to combat operations all over the world.

But this number pales in comparison to the number of military and veteran suicides for the same period. The most recent numbers are estimated at somewhere just over 30,000 suicides for those who served in all the combat operations of the post-9/11 combat theaters. These numbers are just those who have served after the terrorist attacks. The actual total number of veteran suicides between 2005 and 2018 was 89,100, according to a recent Department of Veteran Affairs report.

And these numbers on suicide are not going down. Each year since 2008, the number of veteran suicides has been over 6,300.

Addressing the Crisis From Another Angle

There are no easy solutions to this crisis, but there are some creative programs fighting veteran suicide.

Since 2015, Irreverent Warriors has been hosting events it calls “hikes” that have attracted over 50,000 participants in over 100 cities in 35 states to date.

How does this nonprofit accomplish this? It organizes close to 60 hiking events a year all over the country. These events are designed to accomplish several goals. They get veterans to come out and have an enjoyable experience around other veterans, where they can meet other vets and build a network of people they trust. There are also cookouts and camping trips and other events, but the majority of the events are hikes that are held all over the country and throughout the year.

The organization has a massive network of volunteer coordinators throughout the country. They are tasked with organizing events and building relationships with local businesses and organizations to strengthen the community resources available to veterans at the local level. The national level also works to build partnerships and collaborations that can reach more veterans, with national and local media campaigns to inform veterans of resources for reducing and preventing suicide.

The events are designed to bring together veterans from all eras and from all conflicts in an environment of camaraderie and friendship. Many veterans isolate themselves from society for various reasons and have very few friends. Aside from work, they do not socialize much. These hikes provide opportunities for veterans to get together with others who are like-minded, or who served together during their time in the military. This is also a time when community organizations can speak to veterans about suicide prevention programs and invite veterans to participate in them.

There are always activities that provide information on the local services and programs to prevent suicide. There is also the community itself, which is a supportive and positive one where participants build friendships that can become the emotional support veterans might need when thoughts of suicide occur.

‘Literally Saved My Life’

Jonathan Miller, 51, an Operation Desert Storm era veteran and now a traveling construction worker, got involved with Irreverent Warriors a little over four years ago. “My mental state was a mess,” he said. He was depressed and through Facebook found a local upcoming hike. “I’ve been to close to 40 hikes since that first one.”

“IW has literally saved my life. When I lost my service animal, I spiraled downhill quickly. I’ve made friends that I can trust and open up to, without fear of being looked down on or ridiculed. I’ve had fellow veterans call me when they needed someone just to talk to.”

A Navy chaplain he met through Irreverent Warriors was able to arrange a special visit for him to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was able to say goodbye to a Marine he had served with.

“Through humor and camaraderie, my mental health was improved and prevented this veteran from committing suicide,” said Miller.

Hikes and the Number 22

The hikes themselves encourage conversation, and volunteers build in fun activities while the hike is going on, including during scheduled stops to rest and rehydrate along the way. These hikes can be from 5 to 8 kilometers (about 3 to 5 miles), usually at a relaxed pace. At the end of the hike there is always a small celebration, where old friends and new ones can exchange info or make plans for the day. The hikes are open to all military regardless of when they served, peacetime or wartime, and almost any physical disability can be accommodated.

There is also the occasional signature hike, in which the participants do a 22-kilometer hike (about 14 miles) wearing 22 kilograms (about 49 pounds) of gear in a rucksack and in combat boots. The number 22 is to remind everyone that everyday there are 22 veterans who commit suicide in America.

The hikes usually begin in spring and end in late fall. An untold number of veterans have avoided a dark path and taken the bright path offered by Irreverent Warriors.