One of Thomas Jefferson’s greatest achievements was the Louisiana Purchase, in which the United States acquired 828,800 square miles of the French territory La Louisiane in 1803. Encompassing all or part of 14 current U.S. states, the land included all of present-day Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; parts of Minnesota that were west of the Mississippi River; most of North Dakota; nearly all of South Dakota; northeastern New Mexico; portions of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide; and Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. Today, the land included in the purchase makes up approximately 23 percent of the territory of the United States.

French and Spanish Ownership

At the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, France lost all of its possessions in North America, dashing hopes of a colonial empire. This empire was centered on the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo and its lucrative cash crop of sugar. (“Santo Domingo” is an old name for the island of Hispaniola, where the modern countries Dominican Republic and Haiti are located.)

The French territory called La Louisiane, extending from New Orleans up the Missouri River to modern-day Montana, was intended as a granary for this empire and produced flour, salt, lumber, and food for the sugar islands. By the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Fontainebleau, however, Louisiana west of the Mississippi River was ceded to Spain, while the victorious British received the eastern portion of the huge colony.

When the United States won its independence from Great Britain in 1783, one of its major concerns was having a European power on its western boundary, as well as the need for unrestricted access to the Mississippi River. As American settlers pushed west, they found that the Appalachian Mountains provided a barrier to shipping goods eastward. The easiest way to ship produce was to build a flatboat and float down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to the port of New Orleans, from which goods could be put on ocean-going vessels. The problem with this route was that the Spanish owned both sides of the Mississippi below Natchez.

In 1795, the United States negotiated the Pinckney Treaty with Spain, which provided the right of navigation on the river and the right of deposit of U.S. goods at the port of New Orleans. The treaty was to remain in effect for three years, with the possibility of renewal. By 1802, U.S. farmers, businessmen, trappers, and lumbermen were bringing over $1 million worth of products through New Orleans each year. Spanish officials were becoming concerned as U.S. settlement moved closer to their territory. Spain was eager to divest itself of Louisiana, which was a drain on its financial resources. On October 1, 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of France, concluded the Treaty of San Ildefonso with Spain, which returned Louisiana to French ownership in exchange for a Spanish kingdom in Italy.

Napoleon’s ambitions in Louisiana involved the creation of a new empire centered on the Caribbean sugar trade. By terms of the Treaty of Amiens of 1800, Great Britain returned ownership of the islands of Martinique and Guadaloupe to the French. Napoleon looked upon Louisiana as a depot for these sugar islands, and as a buffer to U.S. settlement. In October of 1801, he sent a large military force to retake the important island of Santo Domingo, lost in a slave revolt in the 1790s.

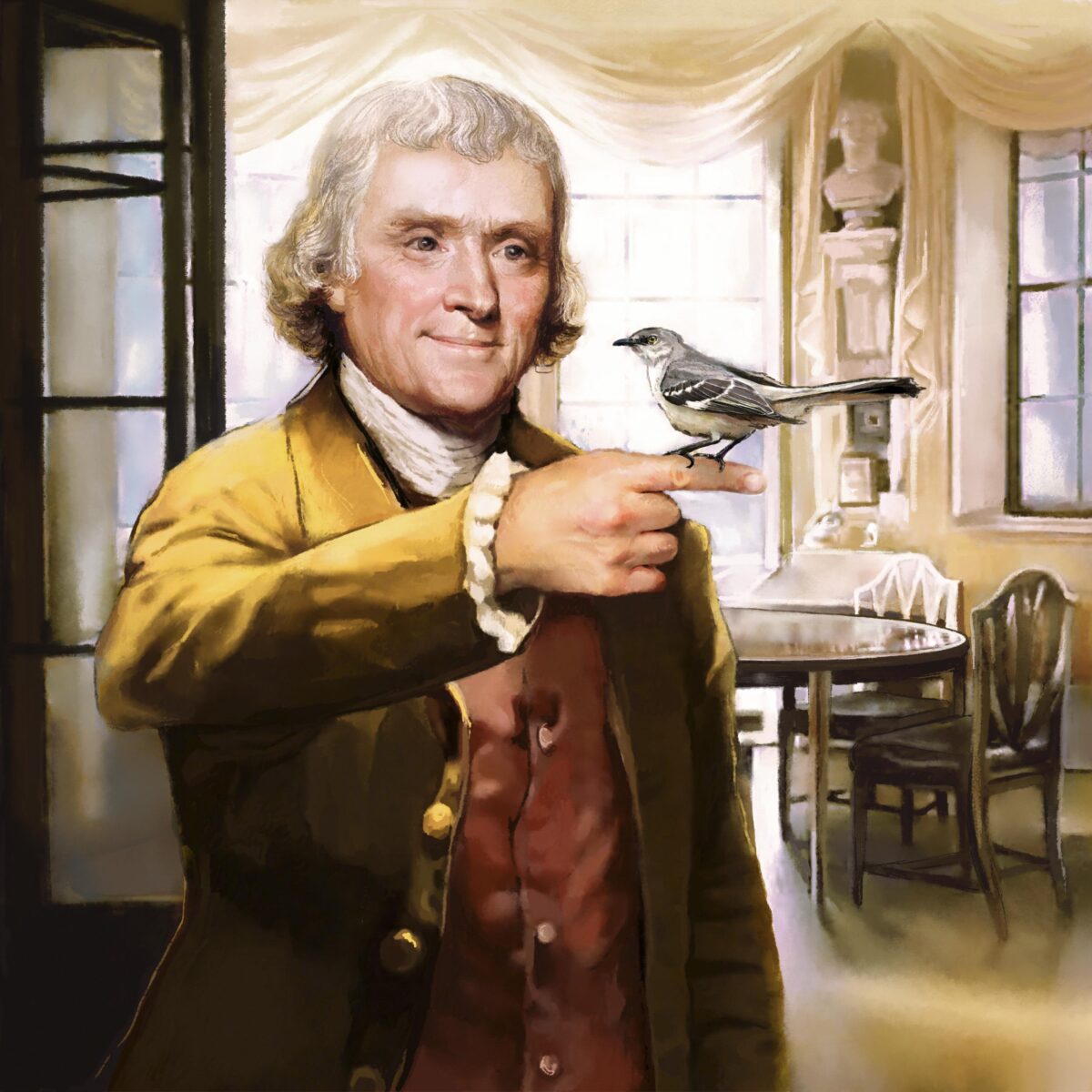

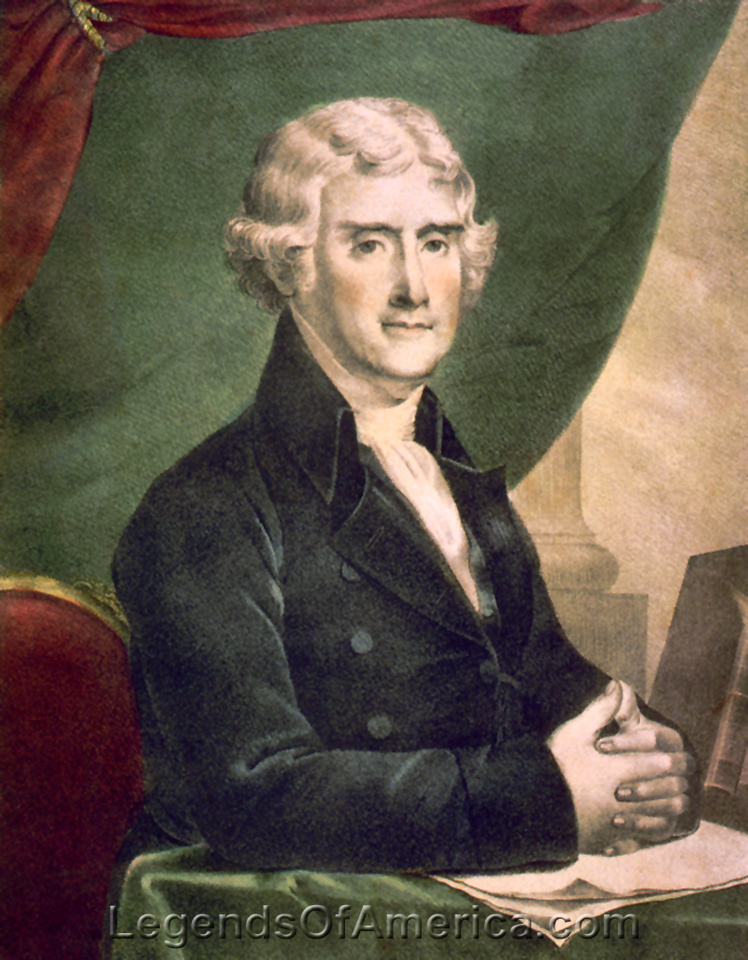

Jefferson’s Plans

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was disturbed by Napoleon’s plans to re-establish French colonies in America. With the possession of New Orleans, Napoleon could close the Mississippi River to U.S. commerce at any time.

Jefferson authorized Robert R. Livingston, U.S. Minister to France, to negotiate for the purchase for up to $2 million of the City of New Orleans, portions of the east bank of the Mississippi River, and free navigation of the river for U.S. commerce.

An official transfer of Louisiana to French ownership had not yet taken place, and Napoleon’s deal with the Spanish was a poorly kept secret on the frontier. On October 18, 1802, however, a strange thing happened. Juan Ventura Moralis, Acting Intendant of Louisiana, made public the intention of Spain to revoke the right of deposit at New Orleans for all cargo from the United States.

The closure of this vital port to the United States caused anger and consternation, and commerce in the west was virtually blockaded. Historians believe that the revocation of the right of deposit was prompted by abuses of the Americans, particularly smuggling, and not by French intrigues, as was believed at the time.

President Jefferson ignored public pressure for war with France, and he appointed James Monroe special envoy to Napoleon to assist in obtaining New Orleans for the United States. Jefferson boosted the authorized expenditure of funds to $10 million.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s plans in the Caribbean were being frustrated by Toussaint L’Ouverture, his army of former slaves, and yellow fever. During 10 months of fierce fighting on Santo Domingo, France lost over 40,000 soldiers. Without Santo Domingo, Napoleon’s colonial ambitions for a French empire were foiled in North America. Louisiana would be useless as a granary without sugar islanders to feed. Napoleon also considered the temper of the United States, where sentiment was growing against France and stronger ties with Great Britain were being considered. Spain’s refusal to sell Florida was the last straw, and Napoleon turned his attention once more to Europe; the sale of the now-useless Louisiana would supply needed funds to wage war there. Napoleon directed his ministers, Talleyrand and Barbé-Marbois, to offer the entire Louisiana territory to the United States—and quickly.

Unexpected Opportunity

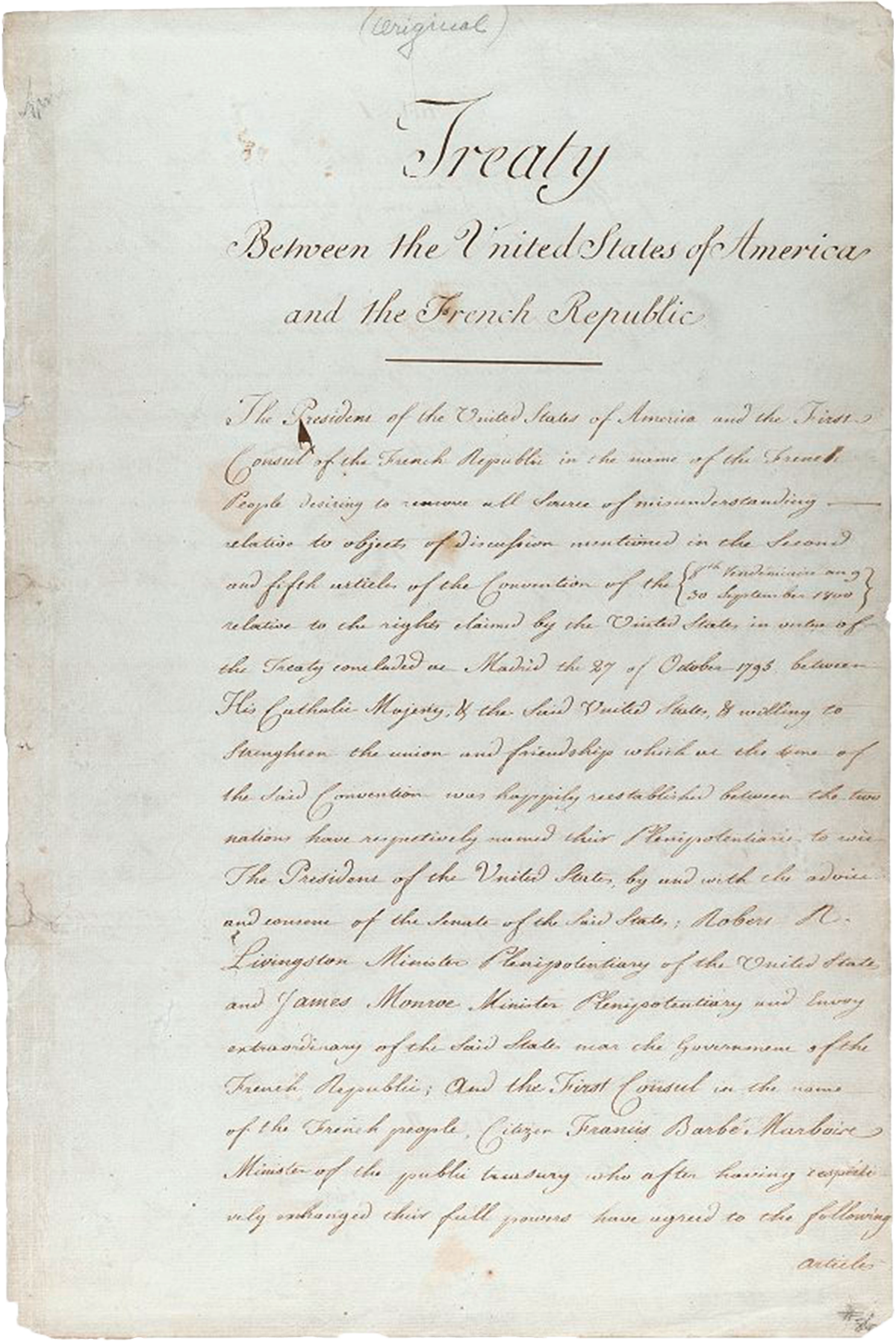

On April 11, 1803, Talleyrand asked Robert Livingston how much the United States was prepared to pay for Louisiana. Livingston was confused, as his instructions only covered the purchase of New Orleans and the immediate area, not the entire Louisiana territory. James Monroe agreed with Livingston that Napoleon might withdraw this offer at any time.

To wait for approval from President Jefferson might take months, so Livingston and Monroe decided to open negotiations immediately. By April 30, they closed a deal for the purchase of the entire 828,000-square-mile Louisiana territory for 60 million Francs (approximately $15 million). Part of this sum was used to forgive debts owed by France to the United States. The payment was made in United States bonds, which Napoleon sold at a discount. As a result, Napoleon received only $8,831,250 in cash for Louisiana.

When news of the purchase reached the United States, President Jefferson was surprised. He had authorized the expenditure of $10 million for a port city, and instead, he received treaties committing the government to spend $15 million on a land package which would double the size of the country.

Jefferson’s political opponents in the Federalist Party argued that the Louisiana purchase was a worthless desert, and that the Constitution did not provide for the acquisition of new land or negotiating treaties without the consent of the Senate. What really worried the opposition was the new states which would inevitably be carved from the Louisiana territory, strengthening Western and Southern interests in Congress and further reducing the influence of New England Federalists in national affairs. President Jefferson was an enthusiastic supporter of westward expansion and held firm in his support for the treaty. Despite Federalist objections, the U.S. Senate ratified the Louisiana treaty on October 20, 1803.

Goodbye France and Spain, Hello United States

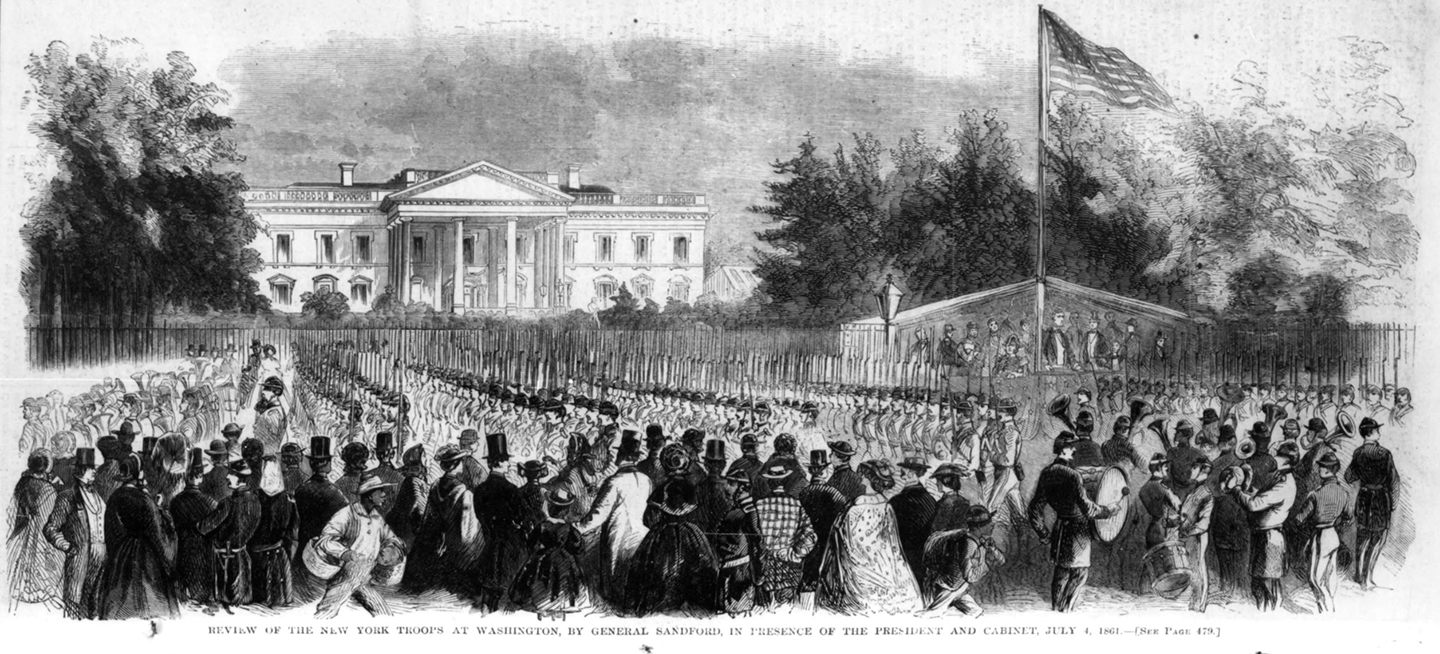

A transfer ceremony was held in New Orleans on November 29, 1803. Since the Louisiana territory had never officially been turned over to the French, the Spanish took down their flag, and the French raised theirs. The following day, General James Wilkinson accepted possession of New Orleans for the United States. A similar ceremony was held in St. Louis on March 9, 1804, when a French tricolor was raised near the river, replacing the Spanish national flag. The following day, Captain Amos Stoddard of the First U.S. Artillery marched his troops into town and ran the stars and stripes up the fort’s flagpole. The Louisiana territory was officially transferred to the United States government, represented by Meriwether Lewis.

The Louisiana Territory, purchased for less than 5 cents an acre, was one of Thomas Jefferson’s greatest contributions to his country. Louisiana doubled the size of the United States literally overnight, without a war or the loss of a single American life, and set a precedent for the purchase of territory. It opened the way for the eventual expansion of the United States across the continent to the Pacific and its consequent rise to the status of world power. International affairs in the Caribbean, and Napoleon’s hunger for cash to support his war efforts, were the background for a glorious achievement of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency: new lands and new opportunities for the nation.

From April Issue, Volume II