Growing up in a Chinese-American community in downtown Sacramento, California, Paul C. Dong rose above adversity. He was the eldest child in a single-mother household and bore adult responsibilities as a youth growing up during the Depression. After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, he inspired Harvey, his eldest son, to believe and achieve no matter the odds.

Currently a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, who has won teaching awards, Harvey faced discrimination when his father bought a home in a predominantly white Sacramento neighborhood during the 1950s. Some neighborhood kids hurled racial slurs at Harvey. He had never before experienced such verbal aggression, and he struggled to figure out that animosity, he said.

It was difficult to process the experience of discriminatory insults from peers, who added the injury of often misidentifying his ethnic background. This experience occurred during the United States’ wars, cold and hot, with China and Korea, and previously with Japan. The elder Dong was there for Harvey in deed and word as he faced adverse social relations.

“My dad urged me to not do anything about it,” Harvey said. “He encouraged me to study harder. His generation had gone through the experience of Chinese Exclusion and segregation,” referring to the law that prohibited all immigration from China until it was repealed in 1943. Despite his dad’s emphasis on pursuing a formal education, Harvey took a rebellious turn, common among youth finding their way in the world. He hung out with peers who lacked a school focus.

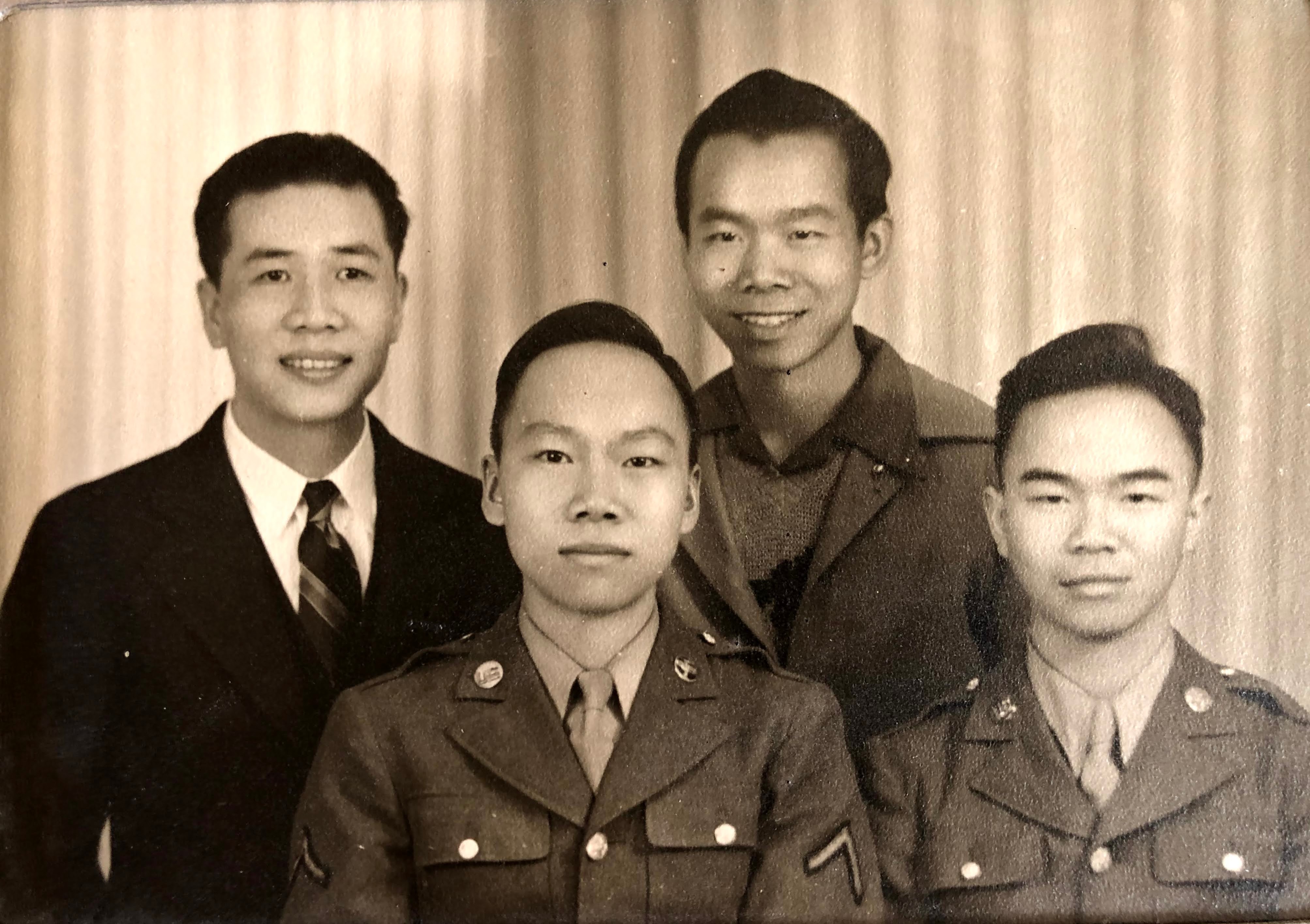

Eventually, though, he enrolled at UC Berkeley during the turbulent 1960s. Harvey even joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program there briefly, following the example of his father and uncles. Their active duty had taken them to the Philippines as the United States fought Japan during World War II. Paul, who turns 100 this year, recently received a Congressional Gold Medal, awarded in recognition of his dedicated service during World War II.

“Dad, after he retired,” Harvey said, “provided his engineering expertise to my construction crew and me. He was super excited about that, helping us to draw up plans to use a pulley system to install heavy beams. He even helped design heat and ventilating systems.”

Harvey drew on his father’s construction expertise in a personal way, too. “I was interested in remodeling our apartment into a handicapped-accessible place for my wife, who uses a wheelchair,” Harvey said. “And he lent his construction design know-how. Later, when I took on a bigger task of building our own house, he enthusiastically helped. So when I went on into construction general contractor work, he was all for it.”

The elder Dong had worked as a mechanical engineer for the state of California for decades before retiring. “As kids, we never really knew what he did as an engineer—just that he was the breadwinner,” Harvey said. His dad’s example of working day in and day out impressed Harvey. “The idea of being a self-made person rubbed off on me,” he said.

The elder Dong took advantage of the GI housing bill to purchase a home directly from a builder; at the time, there were restrictive racial covenants that discriminated against Chinese-Americans and other minorities who sought to buy real estate. “No Realtor would show him properties for sale,” Harvey said, “so Dad bought directly from a fellow veteran and home-builder.”

Harvey took a midlife interest in education, a pursuit that his dad had long supported. To this end, Harvey earned a doctorate at UC Berkeley in 2002, and he began a new career as a lecturer in the school’s Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies Program. His father helped in that undertaking, inspiring Harvey to dig ever deeper into his research and teaching of Asian-American history and issues that concern the Chinese-American community today.

“Dad helped me to translate old Chinese-language newspapers,” Harvey said. “We communicated very well on that.”

The elder Dong had a lifelong love of learning that rubbed off on Harvey. “As a young person, he had secured a study place in the family’s one-bedroom apartment,” Harvey said. “Dad carved a small piece out of a wall to find a quiet spot for his studies. My aunt got a kick out of that, as she thought that Dad had broken the law.”

One thing is certain: Paul was there for Harvey, his country, and his family when it mattered.

“Dad struggled and succeeded,” Harvey said. “He had the idea that his kids could do the same thing, which we did growing up.”

The apples do not fall far from the tree. Like dad, like son.

Seth Sandronsky is a freelance journalist based in Sacramento, California, married to a wonderful woman for the past 37 years. In a previous lifetime, he was a Division II college football player and competitive powerlifter.