The past 20-plus years of mass media reporting on the environment has been dominated by predictions of cataclysmic catastrophe and mayhem, although during my life, I’ve seen a very different story.

Growing up in Eastern Kentucky, deer were few, with no bear, coyotes, turkeys, mountain lions, bald eagles, and certainly no elk. Today, all of these species are present again. Positive things are happening. Wildlife is naturally returning and many species are rebounding with streams cleaner than they’ve been in decades.

How can this be? For years, doomsayers have warned about the end of nature if we didn’t turn the American way of life on its head; they may find it ironic that capitalism funds the successful environmental protections that we do have.

Recently, I took my family to the Salato Wildlife Center in Frankfort, Kentucky. Throughout that gem, you can find the answers of how this can be.

Blight and Restoration

How did the dearth of nature come to be in the first place?

At the turn of the century, the chestnut blight in the eastern part of the country—where strong, rot-resistant chestnut trees that grew since time immemorial fell in mere decades—along with irresponsible clear-cut logging led to ancient forest floors in the mountains to be washed out. The ecology, flora and fauna, and economies tied to chestnuts were devastated. The old-growth forests are now lost except for small pockets such as in Blanton Forest in Harlan County.

At the same time, many wildlife populations crashed due to overhunting and habitat loss. The Great Depression caused remaining species such as deer, rabbits, and squirrels to be hunted for food, with no regard for conservation as people struggled to survive and feed their families. As the Depression ended and most places prospered, much of Appalachia remained impoverished.

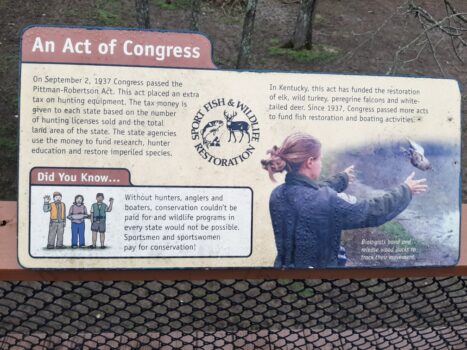

Hunting and fishing licenses are the backbone of conservation and restoration efforts. Hunters funded the successful reestablishment of elk, to the point that we now have regular seasons for hunting.

Bad actors of the past made the Surface Mine Reclamation Act necessary. If you’re unfamiliar with the industry, you may be surprised to learn that reclaiming is part of the regular process, and typically leaves the land better than before it was mined. Why? Because that original land would have washed out about 100 years ago when the chestnut blight ravaged the forest (the restoration of the American chestnut is a subject for another story).

Now, drainage controls are engineered, preventing washout. Native grasses are planted along with nut-bearing trees to promote wildlife. Within a few years, what started out like a scene from “Mad Max Beyond Thunder Dome” is a lush paradise that supports diverse wildlife.

No better example can be found than that of the privately held Appalachian Wildlife Foundation. It’s in the final stages of building a public educational research station, located in Bell County, Kentucky, where the first mountaintop removal mining site in the United States is. People unfamiliar with the reclamation process have no idea it was mined, and the elk couldn’t care less.

Modern-day surface mining is like making sausage: The process is not pretty but the end result is great. The location of the wildlife foundation several decades ago more resembled the surface of Mars or the moon as the top of the mountain was removed of the overburden in order to reach the valuable coal seams below. When coal is too close to the surface, the ground is not stable and it’s not safe to mine underground. To access this coal, the ground above must first be removed.

It is only fitting this wildlife sanctuary was once paraded by those opposed to mining as an example of how awful mining is, because active mining is ugly. This short-sighted view ignored the big picture and the responsible and forward-thinking stewardship by the landowners. When mining was first completed and the reclamation process started, the first few years the land was home to only grasses and low brush and briers taking hold. After a few years and seasons, the soil develops as vegetation decays returning to soil. Per the requirements based on extensive research, the soil is only compacted to certain point to prevent run-off, but not so tight as to prevent trees from easily re-establishing, (early reclamation law required soil be very compacted, inadvertently thwarting vegetation, and thus wildlife returning).

Today most people wouldn’t know Boone’s Ridge was a mine, (with limited active mining still occurring). This is true of most surface mining today, as only contour mining is permitted, where the peak must remain and only the outer edge of a coal seam is mined creating a bench. This bench is filled post-mining and the mountain is returned to its original contours. Once these location are covered with significant hardwood trees, they are indistinguishable from other parts of the hillside not mined to the untrained eye.

Education Works

The many creeks and streams in the region were once clogged with decades of trash and sewage from straight pipes.

Today efforts by private volunteer groups such as PRIDE (Personal Responsibility In a Desirable Environment) remove trash from the streams every April. Over the past decades, septic tanks and new sewage treatment plants have almost ended raw sewage discharge. As a result, fish and aquatic species are flourishing, and even beavers and river otters are returning.

I currently serve on the board of the Kentucky Environmental Education Council, which has played a key part in cultural change for the last several decades by exposing Kentucky students to environmental issues and terms.

Yet another factor changing culture is simply time: The outlaw hardscrabble poacher culture borne of desperate times of the Great Depression has to a large degree died out or become too old and feeble to do much harm. Less fortunate segments of society now have social safety nets and improved infrastructure making it easier to meet basic needs unavailable in the past.

This certainly has helped remove the pressure of necessity to subsist. Most sportsmen today buy licenses and make good faith efforts to follow the seasons, limits, and regulations.

Private corporations can play a role as well, often the ones contributing to funds that make much-needed conservation efforts possible.

Having studied the history of energy and environmental law and being a sportsman myself, I’ve heard much blaming of corporations, industry, and hunters of today for the harms of the past. Education has helped dispel some of these misconceptions. And yes, we do have some real environmental problems in this world; most have root causes traceable to the desperation of poverty, corrupt systems of government, or ignorance of the harm of our actions.

For example, when the Soviet Union collapsed, desperation and anarchy nearly wiped out caviar sturgeon in Russia. Corruption happens, too. Recently, when a mine in Pike County started receiving complaints from surrounding neighbors, it turned out the federal mine inspector was accepting bribes to not enforce the law. Once discovered, it was stopped and the inspector and operator are now in jail. Ignorance of the consequences of actions factors into these environmental problems. Take the example of DDT pesticides; once the harm was discovered, regulations caught up and banned its use.

I saw a wild bald eagle about seven miles from Lexington, Kentucky, just last week. Last summer, a black bear was spotted downtown near a University of Kentucky hospital. These occurrences were unthinkable 30 years ago.

Chris Musgrave is a Kentucky attorney, farmer, and policy professional in energy, environment, agriculture, education, elections, history, and government administration and affairs. He enjoys hunting, fishing, and writing music and articles for fun. He is also a board member of the Kentucky Environmental Education Council and Historic Preservation Review Boards.