When Jingduan Yang was just a boy, his father asked him: “You like to eat meat?”

Yang nodded.

“Well, then,” his father replied flatly, “you’d better learn medicine—or you’re going to go hungry.”

Born in Hefei, Anhui province, in 1962 as the youngest of eight siblings, Yang grew up under the weight of family tradition and the turbulence of a changing China.

His ancestry traces back to renowned Chinese doctors, including a royal physician to the Qing Dynasty emperor. His father, a fourth-generation practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), expected to pass down this legacy to his firstborn son.

However, in Yang’s case, tradition allowed for an exception. With his eldest brother sent for “re-education” in the countryside during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, the duty of upholding the family’s inheritance fell to Yang.

At 13, Yang began shadowing his father, learning the ancient art of Chinese medicine. His father hoped that, at the very least, he could become a “barefoot doctor”—a physician who travels through villages to treat farmers in need, usually carrying a simple toolbox of acupuncture needles and herbs. Most importantly, this way, he could ensure he never went hungry.

In 1977, China reinstated its national college exam system. Yang took the exam and scored high enough to choose his field of study. The opportunities were numerous, but undoubtedly, medicine was his destiny. “I never questioned that,” he said.

Following his father’s advice that “Traditional Chinese medicine is best learned at home” and believing combining it with Western medicine would make him a more capable doctor, Yang enrolled in the prestigious Fourth Military Medical University.

This choice of school, while seemingly straightforward, was discreetly influenced by his family’s troubled political past.

Yang’s father was a former resistance fighter against the Japanese during World War II. Due to his outspoken temperament, he had been targeted by the Chinese Communist Party. As a result, he changed the family name from Tao to Yang to conceal his identity. Now, he urged his children to attend military universities, believing that the trust the communist leadership placed in military graduates would grant a protective veil over the family.

Unbeknownst to young Yang, as he left home for medical school, he embarked upon a journey that would take him from the constraints of communist China to the freedom of the West and from the wisdom of the past to the frontiers of modern medicine.

A Foot in Two Worlds

Once in medical school, Yang found himself straddling two worlds—one rooted in empirical science, the other in millennia-old philosophy. “That’s where the confusion started,” he said.

During summer breaks, he regularly engaged in spirited debates with his father about the discrepancies between the two medical systems.

“In medical school,” he recalled, “we learned blood is produced in the bone marrow. But Chinese medicine says it’s produced by the kidneys—I couldn’t reconcile these two.”

The answer would elude Yang for a decade, the contradiction lingering in his mind. “I couldn’t convince [my father] … and he couldn’t convince me.”

These discussions, at times muddling and frustrating, sowed the seeds for what would become Yang’s lifelong quest: to harmonize the wisdom of the East with the rigor of the West.

By his fourth year, Yang’s exceptional performance earned him a scholarship to study abroad in Sydney. At 21, he was wide-eyed and unaware of the revelations that awaited him.

In Australia, Yang experienced the Western world’s cultural and academic openness. He lived in a seaside cottage under the wing of professor Thomas Stapleton, a stern but warm-hearted mentor. Every morning, the professor made him and his cohort to run along the beach before plunging into the frigid ocean. The training was intensive yet liberating.

Back in China, his curriculum was conventional and rigid—anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry—psychology wasn’t included. In Australia, he had room to breathe, to ask questions, to probe the meaning of life itself.

On one occasion, a fellow medical student asked Yang about the Daoist philosopher Lao Zi. Yang was surprised by his interest, as he had been taught that Lao Zi was a bad person, “feudalist” and “backward.”

“That was embarrassing,” Yang remembered. “It made me aware of the deficit of my own education for my own culture.” But Yang didn’t know better. He had been, in his own words, “brainwashed by communism”—fed a distorted reality.

Academically, his days were filled with discussions of medicine but with an unfamiliar approach.

Once, Stapleton tested Yang with a question about a baby afflicted with diarrhea. Yang confidently listed medical interventions: rehydration, treating infections, and managing symptoms. But Stapleton pressed him further: “What else? What was the mother doing? Where was the father?” This moment taught Yang to think beyond biology and seek other causes—a lesson that would become a cornerstone of his medical philosophy.

“Most doctors focus on fixing symptoms,” Yang reflected, “but we have to dig for the root causes, both direct and indirect.”

Recognizing his passion and aptitude, Stapleton urged him, “You must come to Oxford.”

An Awakening in the West

At Oxford University, as a research fellow in clinical psychopharmacology, Yang made a startling discovery—a group of scientists found that red blood cell formation in the bone marrow was stimulated by a hormone called erythropoietin.

He was stunned to learn this hormone was produced in the kidneys—just as his father had taught.

“I wish he had still been alive when I discovered [this],” Yang said. The discrepancy that long troubled him began to resolve.

Reminiscing on those summer arguments with his father, he recalled how his father also taught him that mood disorders and blood pressure were linked and both could be traced to the liver. At that time, Yang disagreed, “One is a cardiovascular problem, and the other is a problem for the psychiatric department.”

As a fellow, Yang studied how serotonin and dopamine receptors affect mood disorders. While reviewing the scientific literature, he discovered that the majority of the research wasn’t published in a psychological journal, but rather in the journal Hypertension. He realized that blood pressure and mood disorders were both tied to serotonin. Yang then wondered, “Where is serotonin metabolized?” Surprise—in the liver.

“I smiled in my heart,” Yang said. Western medicine, it seemed, was validating ancient Chinese wisdom.

On another occasion, Michael Gilda, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry, took Yang out for lunch and invited him to visit Merton College’s library. There, surrounded by volumes upon volumes of medical botanicals, Yang realized that Western herbal medicine had origins in practices akin to those of Chinese medicine.

These revelations in Oxford marked a turning point for Yang. The two worlds he had straddled began to converge, the wisdom of the past illuminating the path forward.

An Unpredicted Homecoming

Invigorated by his experience abroad, Yang returned to China in 1989, motivated to transform medicine. “I wanted to change China,” he said, brimming with idealism.

However, his homecoming coincided with the Tiananmen Square protests. Many of Yang’s peers marched—yet he chose to keep his head down. He was mindful that as a military officer, he was under tighter scrutiny and could endanger his family and career. He decided to remain on the sidelines, but the anxiety settled in his heart.

Despite the turmoil, his academic career soared rapidly. By 1992, he was the youngest attending physician and assistant professor at the Fourth Military Medical University, poised to lead the neurology and psychiatry departments. Accolades poured in—by all accounts, he was a rising star.

But beneath the veneer of success, he glimpsed a troubling future. He observed that his supervisor, despite his grand achievements, lived in constant fear. The supervisor was very careful about what he said, or even what he thought, constantly self-censoring, said Yang.

Seeing a reflection of his own inevitable path, he thought, “I don’t want to live that life.”

Yang felt the suffocating weight of compromise. He witnessed doctors taking bribes, forming political alliances to secure grants, and navigating the corrupt system. The rigid hierarchy stifled innovation and integrity.

Yang’s mind drifted back to Oxford, where he had tasted true freedom. “I felt I really had human dignity and identity.”

“I wasn’t changing China. China was changing me.”

Yang made up his mind. He would leave for the United States.

His colleagues and family questioned his choice with disapproval, “Why leave when you can be anything you want here?” Yang answered them sternly, “You don’t know what I want—what I want is freedom.”

Facing West and Starting Over

In 1998, Yang landed in snowy Minnesota with a mere $6,000 in his pocket. His medical credentials were worthless in America. Now, with a wife and a young son, he was forced to start anew. Freedom, he learned, came at a cost.

His wife suggested washing dishes at a local restaurant. But fate intervened, granting Yang a teaching position at a community college. There, he taught Westerners about acupuncture and herbal medicine.

It was a transformative period, forcing him to articulate how Eastern and Western medicine could coexist—not to mention in a language not entirely familiar. “I had to bridge the gap. I had to make sense of it myself before I could make sense to them,” he recalled.

Step by step, Yang rebuilt his career. He completed his psychiatry residency at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and a fellowship in integrative medicine at the University of Arizona.

Recognizing a void in Chinese medicine education in the United States, Yang channeled his expertise to co-author a comprehensive TCM textbook for Oxford University Press. He founded the American Institute for Clinical Acupuncture, dedicated to educating and training physicians in clinical acupuncture. If he couldn’t change China, he would bring the best of his heritage to his adopted home.

As his reputation grew, so did invitations to speak at conferences and treat high-profile clients. Yang’s integrative model—a blend of modern science and ancient wisdom—began to take shape.

A New Paradigm

Yang observed the high demand for integrative health solutions that address both mind and body, the former stressed in traditional Chinese medicine and the latter highlighted in Western medicine. This led him to establish his own paradigm, which integrates and balances the two.

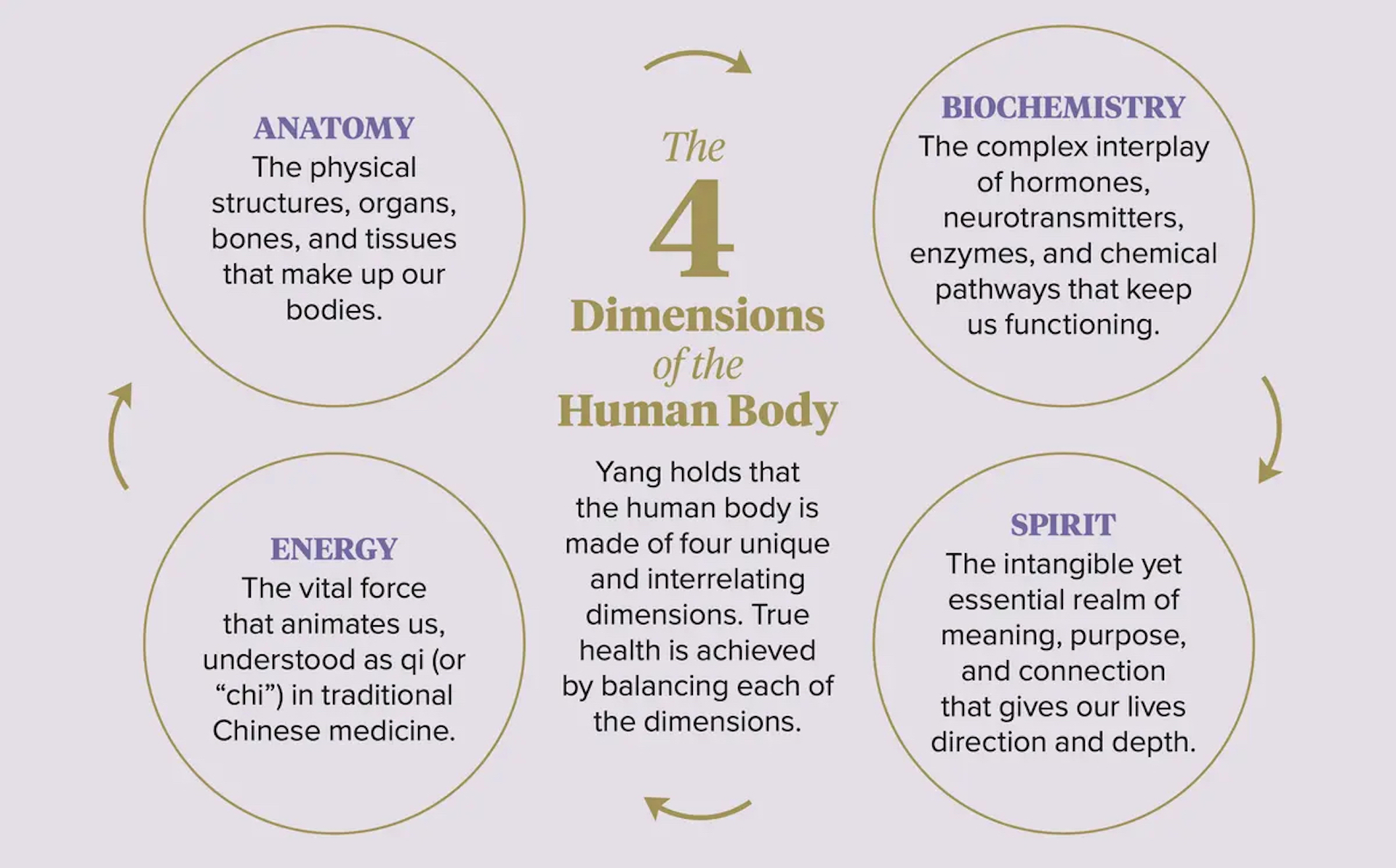

His guiding principle was straightforward. The human body is multi-dimensional, and each dimension must be accounted for in true healing. By his account, these dimensions are anatomy, biochemistry, energy, and spirit.

In Yang’s view, modern medicine often focuses narrowly on anatomy and biochemistry while neglecting the crucial roles of energy and spirit. This imbalance, he believes, lies at the root of many of the chronic illnesses and mental health challenges people face today.

He often brings up the imagery of a car as an example. Even though it has a body structure, oil, water, electrical circuits, and an engine—it still cannot move. It needs a driver to get it going. The same is true for human beings, he suggests, who need the soul, or consciousness, to direct the human body.

“Fundamentally, we are spiritual beings having a human experience,” Yang likes to say. In his practice, he asks patients about their sense of purpose, their relationship to themselves, and their understanding of spirituality and mortality. He sees these questions as inseparable from the pursuit of physical health and well-being.

“We have to define what health really is,” Yang insists. Rather than merely the absence of disease, he sees true health as “the result of physical integrity, biochemical abundance, energetic balance, and spiritual peace.” It’s a lofty ideal, he admits, but one worth striving for.

After years of polishing and practicing his approach, he faces not East nor West but toward the future.

His next goal is to reshape the future of medicine in the United States, and the best way to inspire change is by leading through example.

A New Medical Center

Today, Yang is the CEO of Northern Medical Center in Middletown, New York—a medical center designed to combine ancient and modern wisdom to treat each patient as a whole person. The center brings his vision to life by offering integrative care that blends standard medical treatments, acupuncture, and herbal therapies all under one roof. Currently, it serves more than 1,000 patients a month.

Rather than offering traditional Chinese medicine as an add-on, Northern Medical Center designs its treatments on the anatomy, biochemistry, energy, and spirit model, giving each of the four dimensions the same weight.

Traditional Chinese medicine should not be seen as “complementary” or “alternative” but “essential,” says Yang.

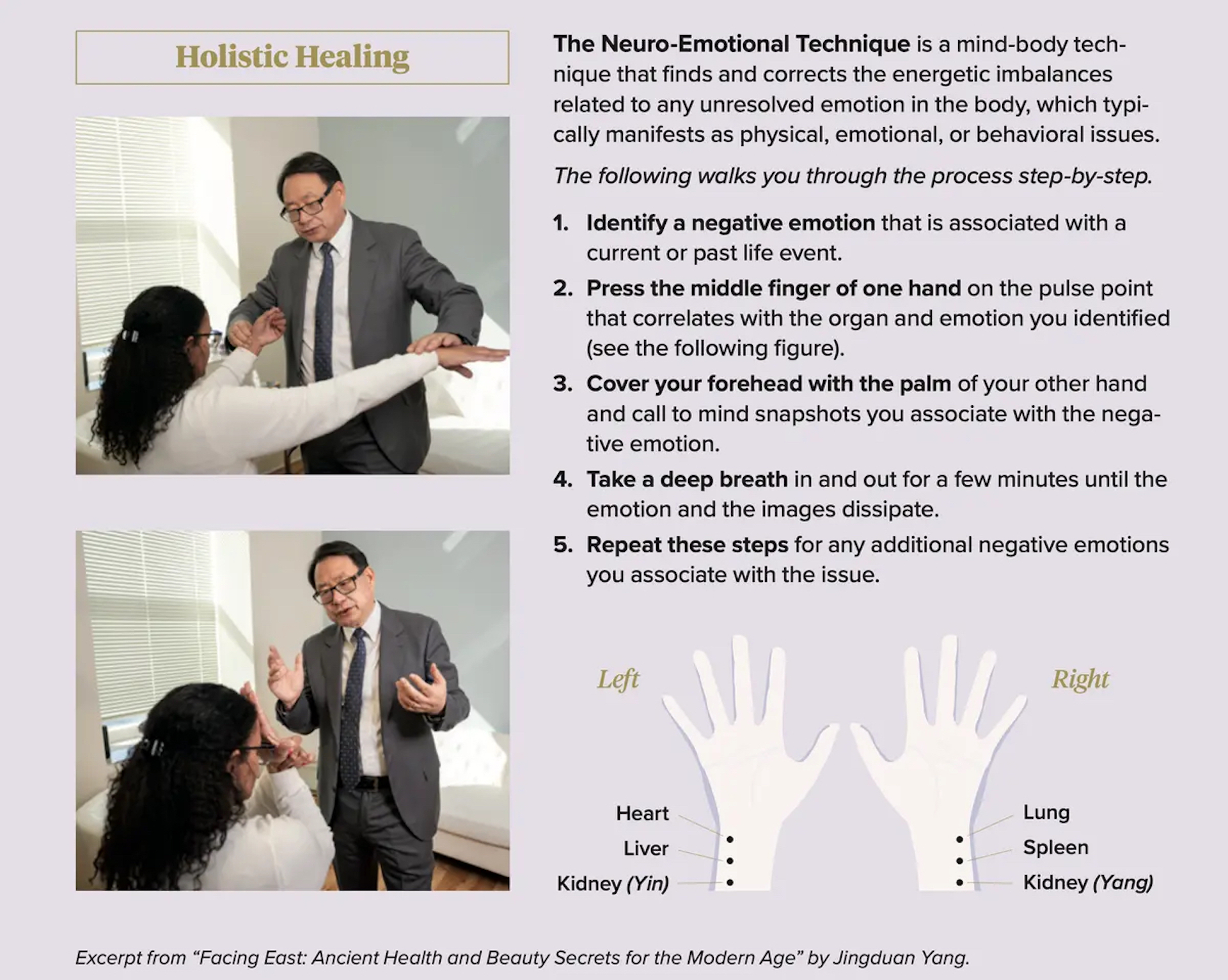

For instance, Yang employs a technique called neuro-emotional technique (NET). While using traditional Chinese medicine’s understanding of energy meridians and emotional blockages, NET introduces a systematic Western approach to identify where unresolved emotions are stored in the body.

The technique can pinpoint energetic blockages and release them. He recalls a patient named Rob, whose smoking habit persisted despite numerous attempts to quit. Using NET, Yang helped Rob discover that his habit was rooted in academic pressure from his father years ago. Once this emotional block was identified and released, he quit smoking and remained tobacco-free.

Another key emphasis of the center is caring for patients with humanity and compassion.

The staff notes that Yang personally spends substantial time with each patient. “They’re more like dialogues than consultations,” said Qinyang Jiang, his medical assistant. Yang wants to understand the context of the patients’ lives, not just their lab numbers.

This focus has led many patients to experience breakthroughs after years of ineffective treatments elsewhere, said Yang. For instance, one veteran with severe PTSD and chronic depression sought care at multiple hospitals to no avail. After receiving integrative treatments, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, acupuncture, and trauma-focused therapy, the patient achieved long-term relief and returned to meaningful daily life.

The Triple Doctor

For Yang, transforming health care begins with reimagining the role of the physician.

“If your doctor is paid only to prescribe medicine, to talk to patients for 15 minutes, and to perform surgeries, they’re not motivated to do anything else,” he said.

“Imagine a system where primary care physicians are paid equally for preventing illness as they are for treating it. That would fundamentally change our approach to health.”

Yang’s vision for this new kind of physician draws from the ancient wisdom of Chinese medicine. He recounts the story of Bian Que, a legendary doctor who, when asked by the emperor if he was the best, replied, “No, I’m not. I only treat sickness. The best doctor is one who can prevent people from getting sick.”

Bian Que went on to say, “The best doctor is one who can heal the nation. The second best heals people. The third merely treats diseases.”

If you look at our American system today, Yang points out, most doctors are dealing with diseases, but not the root cause. Therein lies both the problem and the opportunity.

He wants to educate the next generation of health care leaders to be “triple doctors”—“those who can shape public health policy, treat patients holistically, and address diseases effectively.”

A Vision for a Healthier America

Northern Medical Center is just the beginning. Having spent over four decades studying wide-ranging disciplines across four continents, Yang believes the American health care system needs an overhaul.

Despite a $4.5 trillion budget, the current system prioritizes intervention over prevention and disease over health. Yang believes integrative medicine is the missing piece. Without it, “we’re not going to make America healthy again.”

He believes that, given just 0.0046 percent of the health care budget, he could demonstrate what a health care system looks like, with Northern Medical Center leading as an example.

Yang has a grand plan—to build a local system that demonstrates how integrative health care can cost less, work better, and be replicated globally.

Yang is working to create a model that includes a medical school, hospital, and research institute. In this system, doctors are educated to see patients as whole beings, and health is defined not by the absence of disease but by the presence of balance.

It’s an ambitious vision, but one already taking shape at Northern Medical Center.

“Knowing the type of person he is, Dr. Yang is well-suited to a task like this,” said Robert Backer, a psychologist and former colleague. Yang can galvanize people and inspire them to share in his vision. More people are joining the team, convinced by his ideas and convictions.

Yang’s demeanor is calm and thoughtful, yet shifts when it’s time to get things done—perhaps a remnant of his military training. “He sets a goal and makes it happen,” said his medical assistant.

For Yang, it’s not about personal legacy. “What we do in this lifetime will contribute to the future,” he said. “I want our children and grandchildren to live in a better, healthier, more beautiful world.”

Jingduan Yang is, by his own admission, a dreamer, but he’s not waiting for that world to arrive.

He’s building it.

From May Issue, Volume V