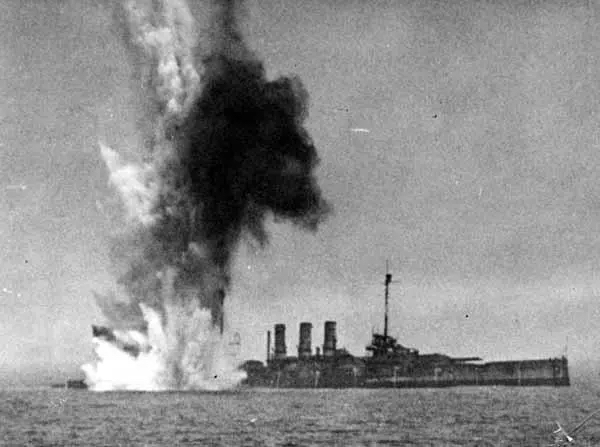

Shortly after noon on July 21, 1921, bombs from American aircraft exploded beside the former German battleship Ostfriesland, already damaged by several previous bombing runs. Within half an hour, the enormous ship began sinking by the stern, rolled over, and soon slipped beneath the waters of the Chesapeake Bay.

Observers on the nearby U.S.S. Henderson could scarcely believe what they’d seen. For the first time in history, aircraft had sunk a battleship. Historian Roger G. Miller relates that some of the naval officers present, perhaps realizing what this event meant for the future of naval warfare, had tears in their eyes.

Meanwhile, in the cockpit of an airplane above the Bay, a vindicated Gen. Billy Mitchell was ecstatic over the results of this experiment, which he himself had devised. His predictions regarding the superiority of aircraft over the battle wagons of the fleet were now visible to all. He was ushering in a new era in naval warfare.

Or so he thought.

The Advocate of Air Power

William “Billy” Mitchell (1879–1936) grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A youth with a keen sense of adventure, he dropped out of college at age 18 and enlisted in the Army during the Spanish–American War. He was assigned to the Philippines, where he was soon commissioned as a lieutenant, in part because of the influence of his father, a former U.S. senator. He later served in Alaska, where he helped construct the Washington–Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System.

Back in the States, he carried out different assignments while becoming increasingly fascinated with aviation, predicting as early as 1906 that it would change warfare forever. In 1916, he took private flying lessons, and with America’s entry into the war in Europe in 1917, he quickly showed himself a daring and resourceful pilot, rising rapidly through the ranks. In 1918, he had charge of over 1,400 American, French, British, and Italian aircraft during the pivotal Battle of Saint-Mihiel. By the war’s end, he had won numerous awards and medals and was the Assistant Chief of Air Service.

Following his return stateside, Mitchell remained active in the upper echelons of the Air Service. To him, it was clear that air power would soon dominate the battlefield, not only on land but on the sea as well, and he pushed hard for an air corps separate from the other branches of military service. In those few years, he also made strenuous efforts to advance aviation as a multi-faceted military tool, helping to develop, for example, bombsights and aerial torpedoes, and he urged his Army pilots to aim at setting speed and endurance records.

The Critic and His Court Martial

Mitchell had few qualms about irritating his superiors. Gen. John H. Pershing’s 1923 efficiency report perfectly captures his flamboyant personality: “This officer is an exceptionally able one, enthusiastic, energetic and full of initiative (but) he is fond of publicity, more or less indiscreet as to speech, and rather difficult to control as a subordinate.”

The mix of these characteristics with his often strident advocacy for a separate air force brought some major pushback from both the Navy and the Army. Two years before his bombing demonstration on the Chesapeake, for example, Mitchell had testified before a congressional committee that the Navy was ignoring the role of airplanes at sea in favor of constructing more ships. Secretary of War Newton Baker and then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt immediately refuted these charges.

With the sinking of the Ostfriesland and other ships from the air, Mitchell would make his point, but his continued hectoring of his military and civilian superiors to do more, to build more planes and to create an independent air force, undoubtedly caused hard feelings and divisions that hurt rather than helped his cause.

In 1925, the Navy’s dirigible Shenandoah crashed as the result of a storm. Following this catastrophe, Mitchell publicly attacked both the Army and the Navy for what he saw as their “incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the national defense by the Navy and War Departments.”

With this pronouncement, he was charged with insubordination and court-martialed. He made the courtroom a platform for his views on aviation, but he was nonetheless found guilty and was suspended from active duty for five years. Rather than serve this sentence, Mitchell resigned from the Army in 1926 and retired to a Virginia farm, where he continued to write and speak about the pressing need for an air force and about the danger of falling behind other countries in aerial strategy and technology, particularly Japan.

The Pearl Harbor Prophet

Because of his court martial, Billy Mitchell is often called a prophet without honor in his own country. In addition to his farsighted take on military aviation, in one regard he also demonstrated his talent as a clairvoyant in a much more specific way.

In 1923, the Army dispatched Mitchell to the Pacific for a year to collect information and gather intelligence. Though he was likely sent on this mission to silence his ongoing criticisms, Mitchell took his assignment seriously and submitted a 323-page report on his return. Years later, this document, which had quite a bit to say about the Japanese military, predicted that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor by air and sea at some point in the future. After listing specific points they would attack on the island of Oahu and on the Philippines, he then wrote:

“Attack will be launched as follows: bombardment, attack to be made on Ford Island [at Pearl Harbor] at 7:30 a.m. … Attack to be made on Clark Field (Philippine Islands) at 10:40 a.m.”

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese initiated such an attack, just as Mitchell predicted. He was off on his timing of these assaults by an hour or less. Moreover, as he had foreseen, the airplane played a crucial role in every Pacific naval battle of the war, from Pearl Harbor to the surrender of Japan.

In 1946, 10 years after his death and one year after the Japanese were defeated, the U.S. Congress awarded William Mitchell a special Congressional Gold Medal. On the back of the medal are these words: “For outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of American military aviation.”

The passionate prophet of air power had at last received his hard-won recognition.

From Nov. Issue, Volume IV