If you ask what education means to people, most will think “school.” If they are jaded, “debt.” But for the first great American family, it was much more than this.

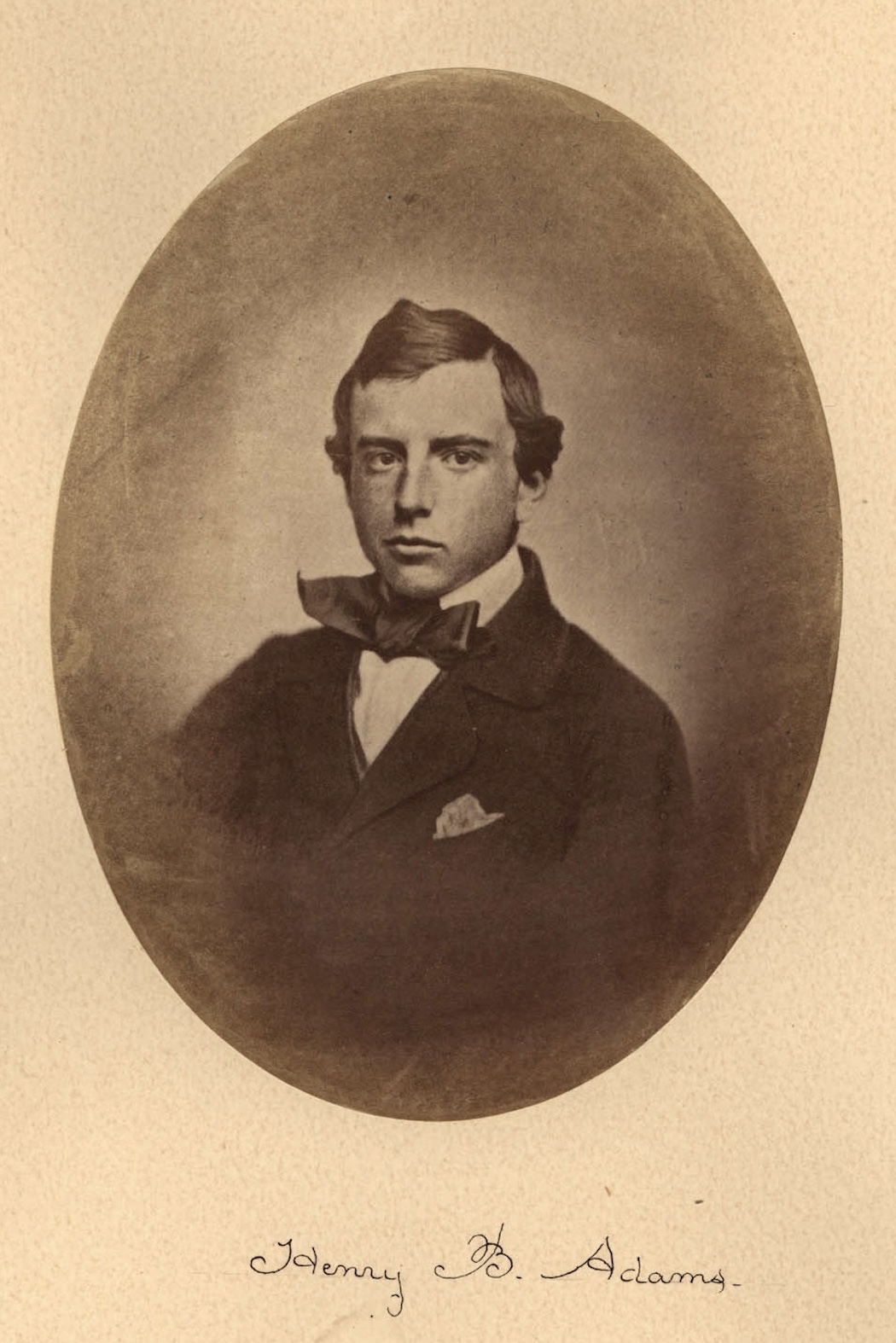

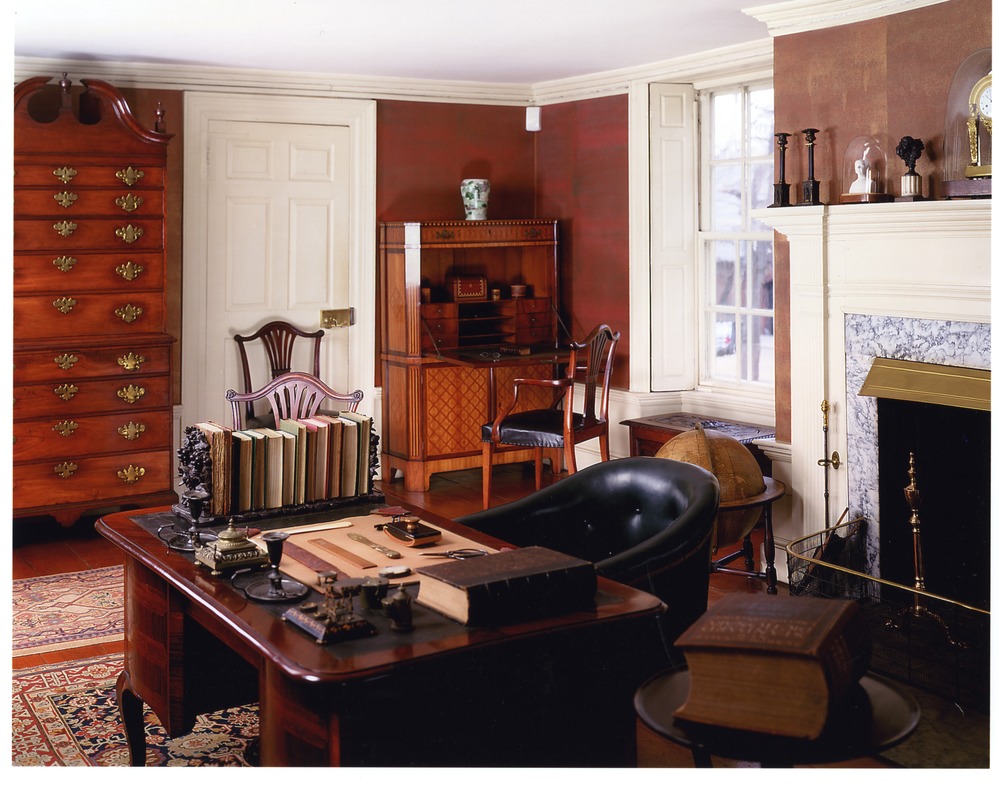

In his autobiography, “The Education of Henry Adams,” the author describes growing up within a celebrated lineage that, by his lifetime, had become a cultural institution. During his childhood, Henry wrote, he would often transition between the Boston home of his father Charles Francis Adams, Lincoln’s future ambassador to England during the Civil War, and the home of his grandfather John Quincy Adams, where he played in the former president’s library. Sitting at his writing table as “a boy of ten or twelve,” he proof-read the collected works of his great-grandfather John Adams that his father was preparing for publication. While practicing Latin grammar, he would listen to distinguished gentlemen, who represented “types of the past,” discuss politics. His education, he reflected, was “an eighteenth-century inheritance” that was “colonial” in atmosphere. While he always revered his forebears and felt they were right about everything, he observed that this learning style did not sufficiently prepare him “for his own time”—a modern age that was increasingly defined by technology, commerce, and empire.

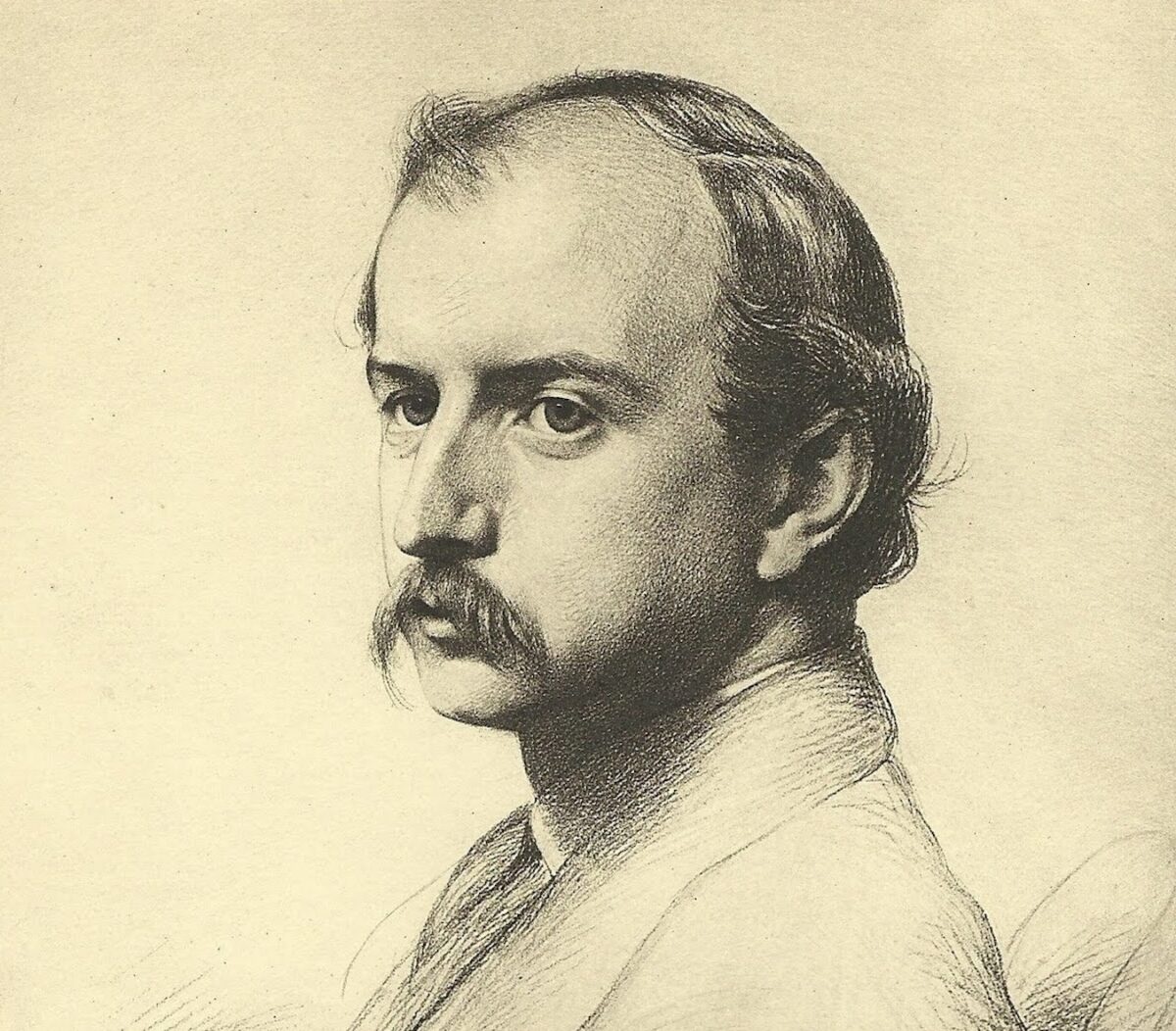

Henry Adams is today considered one of America’s greatest historians. Given this, one would probably conclude that his education served him exceedingly well, even if he hoped to produce history rather than merely record it. The substance of his educational ideals was, when stripped of their luxurious trappings, very similar to that of our second and sixth presidents. Although this was precisely the problem for a young man growing up in a new industrial epoch, there is much to admire about this cultivated reverence for tradition. Values, unlike skill sets, do not become obsolete.

A Father Teaches His Son

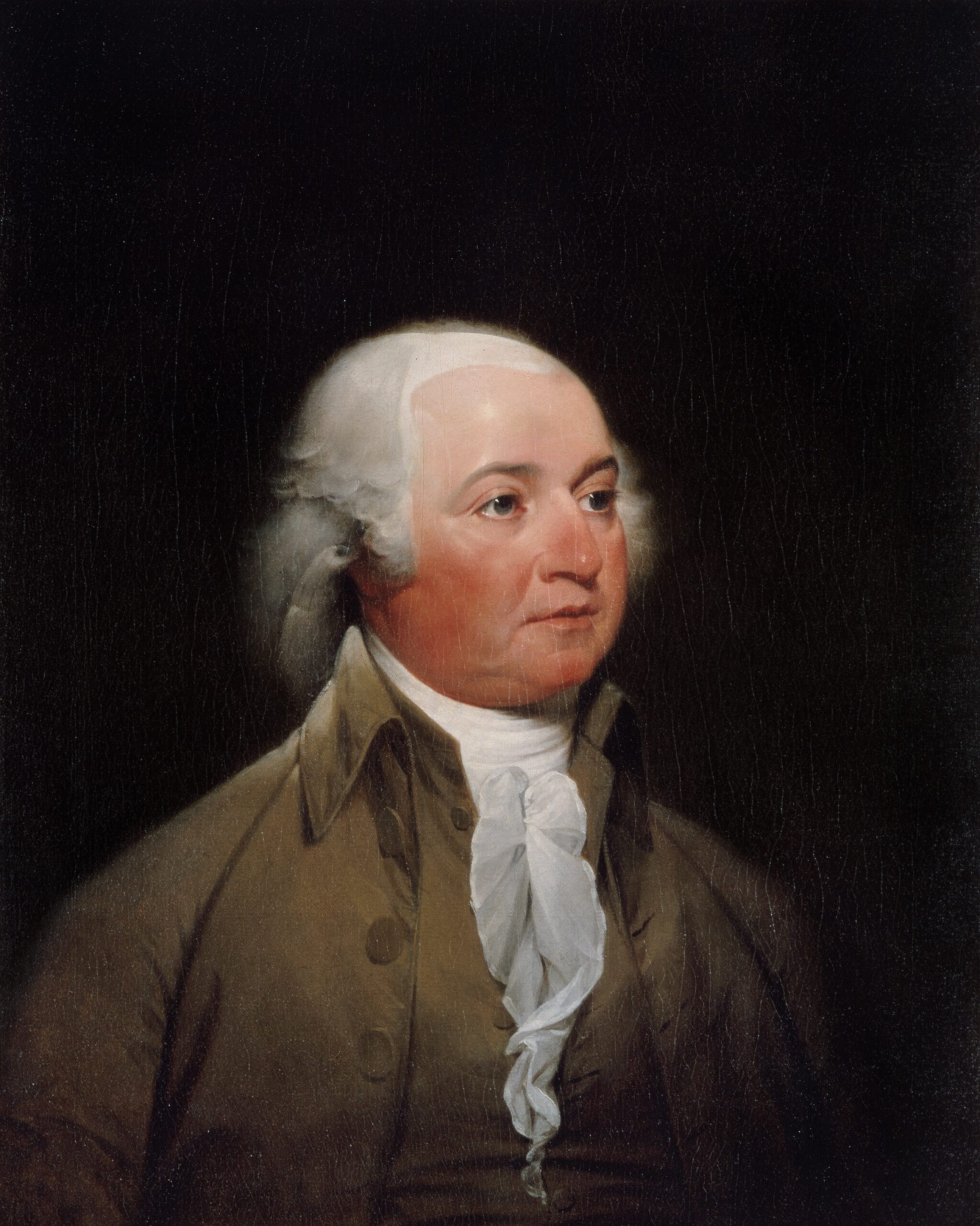

The wealth and privilege Henry Adams experienced was far removed from the boyhood circumstances of his most famous forefather three generations previously. John Adams was born in a simple farmhouse where the family’s only valuable possessions were three silver spoons. The key to his rise was education. Not only of the formal kind, but of character. John took inspiration from his descendants, “a line of virtuous, independent New England farmers.” When he complained of losing interest in his studies due to a churlish teacher at his schoolhouse, his father, a deacon, enrolled him in a private school. Later, the deacon sold 10 acres of land to pay for his son’s college fund.

John admired his father, striving to embody the qualities of sincerity and patriotism he instilled. He called the deacon “the honestest man” he ever knew and passed on these ideals to his own son, John Quincy Adams. While John was in Philadelphia attending the Continental Congress, he instructed young “Johnny” through letters. Writing to Abigail on June 29, 1777, he said, “Let him be sure that he possesses the great virtue of temperance, justice, magnanimity, honor, and generosity, and with these added to his parts, he cannot fail to become a wise and great man.”

In letters to John Quincy during this same year, John advised his son to acquire “a taste for literature and a turn for business” that would allow for both subsistence and entertainment. Reading the historian Thucydides, preferably in the original Greek, would provide him with “the most solid instruction … to act on the stage of life,” whether that part be orator, statesman, or general. While John was away, Abigail constantly upheld her husband to John Quincy as an example of professional achievement and courage. She encouraged him to study the books in his father’s library and forbade him from being in “the company of rude children.”

For the Adamses, books were not just the means to a career, but a key to unlocking the sum of a person’s life. Education encompassed experience, conduct, and social ties. Like his grandson Henry, young John Quincy was sometimes unsure whether he would be able to live up to his ancestors’ example.

A Family Heritage

John instructed John Quincy more directly when taking him along on diplomatic missions in Europe. In Paris, John Quincy began keeping a daily journal at his father’s request, recording “objects that I see and characters that I converse with.” John Quincy observed his father staying up at all hours to assemble diplomatic reports and would later emulate this diligent work ethic.

He then accompanied John to Holland. At the age of 13, he “scored his first diplomatic triumph,” according to biographer Harlow Unger. The precocious young student, dazzling professors with his erudition at the University of Leiden, caught the eye of an important scholar and lawyer named Jean Luzac. John Quincy introduced Luzac to his father, then struggling to convince the Dutch government to give America financial assistance in its costly war with Britain. Luzac was impressed with the Adams family, advocated their cause of independence, and succeeded in securing crucial loans for the desperate young nation.

During this time, John Adams encouraged his son to continue studying the great historians of antiquity: “In Company with Sallust, Cicero, Tacitus and Livy, you will learn Wisdom and Virtue.” He closed his letter by emphasizing the importance of the heart’s authority over the mind: “The end of study is to make you a good man and a useful citizen. This will ever be the sum total of the advice of your affectionate Father.”

John Quincy, ever the obedient son, attended to both the wisdom of the distant past and his family heritage that enshrined it. While following in John’s footsteps as a diplomat, and later president, he would pass these values on to his own children.

The success, achievement, and public legacy of the Adams family has everything to do with this conception of education as a living inheritance. Writing over a century later, Henry Adams saw the role of learning as a lifelong endeavor that was difficult to justify through any specific practical or monetary measurement. But, he added, “the practical value of the universe has never been stated in dollars.”

From March Issue, Volume 3