This year marks the 60th anniversary of the start of President John F. Kennedy’s administration. When he took office in January 1961, he ushered in a new sentiment for the country. That sentiment was all about youth.

At 43, JFK was the nation’s second-youngest president, and he was good-looking to boot. The First Lady was also young and good-looking, and their two young children were adorable. It was all about youth.

JFK succeeded President Dwight D. Eisenhower. While both had served in the military during World War II, they were from opposite ends of the age spectrum. Eisenhower, known as Ike, was a career soldier, and had reached the rank of five-star general in the U.S. Army by the end of his military career. JFK, while an officer in the Navy, was far younger, and only rose to lieutenant during the war.

“What had happened in 1960 was that the junior ranks of the military in World War II replaced the generals,” said James Piereson, a historian and fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “That was part of the generational change that happened. Kennedy was, of course, quite pro-military,” he said. “JFK gave luster to military service,” he added, having “very much campaigned on his war record” in 1960.

So, what was it like being young and in the service during the Kennedy administration?

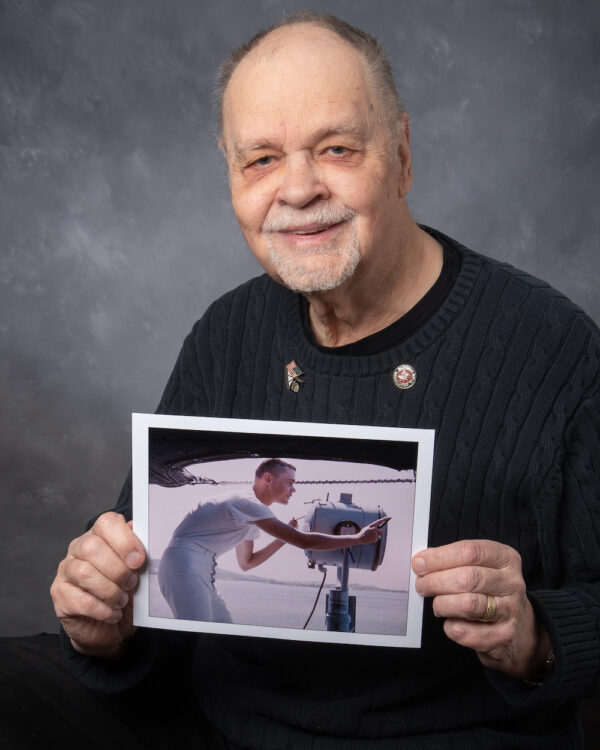

Bob Hogan was a gunnery officer and lieutenant junior grade on active duty in the Navy from 1960 to 1963, essentially the entire duration of JFK’s time in office. He was commissioned at age 22. “I was blown away by JFK’s Navy war record, his charisma, style, and wit,” he said. “I was immensely energized by his call to service, and really believed in it. His seeming idealism, his patriotic values—I was completely taken in.”

Tom Fryer had the thrill of a lifetime when JFK handed him his diploma and commission. They shook hands at Fryer’s graduation ceremony from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1963. “I felt so honored, so humbled,” said Fryer, who was also 22 at the time.

The American president is also commander-in-chief of the nation’s military. In October 1962, JFK had to make some difficult decisions in that role. The United States and the USSR were fighting the Cold War. Nikita Khrushchev was JFK’s counterpart in communist Russia. A U-2 reconnaissance photo of Cuba confirmed that Khrushchev had placed nuclear missiles on the island, just 90 miles off the coast of Florida.

JFK responded by ordering a naval blockade around Cuba, and essentially told Khrushchev that the missiles had to go. If they didn’t, there would be war. A nuclear war.

This period, known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, was essentially a naval operation. But the entire military, worldwide, was ready for deployment, including a possible invasion of Cuba.

Harry Moritz was at Morse Intercept School at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, at the time. “One day, we marched back to our barracks and were held for an announcement. We were asked if anyone spoke Spanish. Several guys raised their hands. They were pulled to one side, told to pack their gear, and they were sent on a ‘special assignment’ TDY (temporary duty station). They disappeared and were never seen again,” he said. “We non-Spanish folks stayed in Morse school, and in the dark, like the rest of the USA, crapping our pants.”

Gary Mahone was a Morse interceptor, stationed in Hakata, Japan. “During that time, we were on red alert and worked 12-hour shifts, 24/7,” he said. “All leaves and terminations were canceled. Very tense times.”

The Air Force Academy that Fryer attended was in Colorado, not far from the North American Aerospace Defense Command (called NORAD), which conducts aerospace warning and control for the United States. “If the Russians would have come after us, that was a prime target,” said Fryer.

However, according to Fryer, Soviet missiles weren’t all that accurate at the time, so if they fell 15 miles short of their target, the academy could easily be hit. “In preparation for that, we held some drills,” he said. The academy was built with underground tunnels that distributed its utilities. Top brass decided the safest place for the cadets was in these tunnels, which no one really knew about.

Hogan was on a destroyer, which was part of the task force that was going to invade Cuba. His ship was the submarine screen and would provide shore bombardment should the invasion happen.

Hogan spotted a Russian submarine tailing them. “I heard his torpedo doors open,” he said. That meant the Soviets were preparing to attack. Hogan had his hand on the trigger, let his captain know he had positive identification, and requested permission to fire.

Had permission been granted, this very action would have kicked off a nuclear war. However, he was “in a system” and “the system has its rules; you follow the rules.” He would have obeyed the order to fire if it had been given.

“I was (expletive) my pants,” Hogan recalled. “There was a long pause, and the captain said, ‘Classify your contact as a whale,’” instead of an enemy submarine. “I was really glad when the captain chickened out.”

With a nuclear war between the two superpowers looming, Khrushchev eventually gave in and agreed to remove the missiles.

Joe Schmidt was a 21-year-old signalman on a destroyer in the blockade. His job was to directly communicate with the Russian merchant ships as they removed the missiles from Cuba. “With a flashing light, we would send a message to them, and we had to ask them, ‘What is your cargo?’” he said. The expected reply was, “Missiles.” Schmidt would relay that message to the captain, who would relay it to the naval air station in Key West, Florida.

It was understood by everyone involved that the Soviet merchant ships were carrying the missiles and nothing else. “Anything coming out of Cuba at that point was only coming out with missiles on it. They weren’t bringing cigars,” said Schmidt with a laugh.

Key West would then dispatch a P2V Neptune anti-submarine aircraft to fly over the Russian ship to photograph its cargo. The only time Schmidt was in contact with a Soviet ship, it was after midnight and completely dark.

“They had these huge searchlights on the wingtips,” he said. “And they lit that ship up—that plane lit it up—it looked like it was 12 o’clock in the afternoon with those lights.” Even though the two sides spoke entirely different languages—ones that don’t even share the same alphabet—there was a code that both understood, which made communication possible.

JFK’s presidency is fondly referred to as “Camelot,” and the consensus among those who served in the military during his administration is that, for different reasons, it was an exciting time. As Hogan put it, “Best and worst experience of my life.”

Dave Paone is a Long Island-based reporter and photographer who has won journalism awards for articles, photographs, and headlines. When he’s not writing and photographing, he’s catering to every demand of his cat, Gigi.