The hourlong flight across lower Michigan was nearing completion when Ed Cole found himself in fog on his approach to Kalamazoo. It was May 2, 1977—an otherwise routine Monday morning. Before takeoff from Pontiac, the suburban airfield north of Detroit, Cole had chatted in a “jolly” mood with a hangar employee and mentioned seeing purple martins at home. After nursing a cup of coffee, he defied the weather warnings, choosing to rely on the instruments in his twin-engine Beagle S.206.

Lee Huff and her dog witnessed Cole’s last moments.

“The plane circled my house three or four times, and the dog put up such a racket that I ran outside in the backyard to see what was going on,” she told a correspondent. Cole’s plane crashed, causing a “terrible boom.” He was 67 years old.

Shock prevailed among the 400 mourners leaving the funeral service that week. The faces of Henry Ford II, Lee Iacocca, George Romney, and Roger Smith reflected incomprehension, as if the premature death of such a towering figure was impossible.

Weeks before his death, Cole had signed up to run Checker Motors Corp. in Kalamazoo, located about 60 miles from his own native village of Marne (formerly Berlin), Michigan. Founded in 1922, Checker made about 5,000 cars per year of the Marathon. This sturdy, dowdy sedan, introduced two decades earlier, was popular with taxicab services. In other words, after General Motors (GM), Ford, Chrysler, and American Motors, Checker was the fifth-largest automaker. “I’m number one at number five,” joked Cole, who liked to gab with reporters.

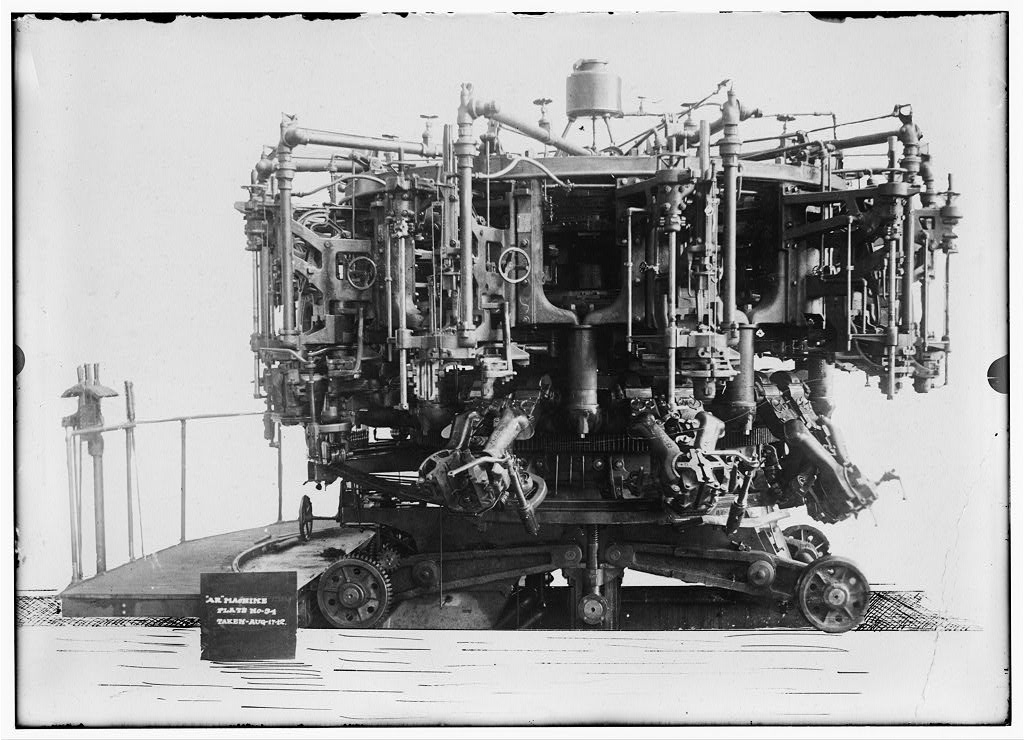

He had retired as GM president 3 1/2 years earlier. His career started in 1930 with a 45-cent-per-hour job in the corporation’s Cadillac Division. Until the 1950s, the divisions within GM were self-governing; Cadillac had its own suppliers and plants for cars, but also manufactured battle tanks for the military. Besides working on GM’s first automatic transmission, Cole straightened out issues in tank performance. He became chief of tank design in 1943. When World War II ended, he worked on Cadillac’s new V-8 engine. Then, as the Korean conflict broke out, he was put in charge of the Walker Bulldog tank.

Flying his own Beechcraft Bonanza, he searched around for a factory and found a building in Cleveland, but had to remove 39 million pounds of beans. A staff of 7,000 people was hired to assemble the tanks. Cole told a newspaper that his team of 14 managers and he worked so hard to get the operation up and running that they were “eating four meals a day and getting skinny.”

The late automotive editor David E. Davis Jr. knew Cole. “There was nothing he couldn’t accomplish, no problem that couldn’t be solved,” Davis once said.

Cole would have been happy to stay put, but the Chevrolet Division called in 1952. “I was doing my own thing and designing engines in my department,” he said. His talents were needed elsewhere. “At that time, Chevrolet was making a little six, a grandmother-type car. Nobody had ever built an enthusiast-type of car around Chevrolet.” Ford had featured its V-8 engine since 1932. Chrysler had just introduced its Hemi V-8, which would become legendary. Cole and the boys got together in a room at Cleveland’s Lakeshore Hotel and drew up plans for the new Chevy V-8 “as a form of entertainment.”

Being appointed as Chevy’s chief engineer and returning to Detroit, Cole led the development of the compact lightweight power plant with four cylinders banked to one side, four more to the other, and a 90-degree “V” angle between them. It incorporated all of the latest internal design features and some breakthrough manufacturing techniques. The V-8 would make its debut in the 1955 Chevy. GM’s top boss, Harlow “Red” Curtice,” stepped into the picture and said he wanted the car to have a “hound dog” look. Cole stopped by the design studio almost every day to see it take shape.

Designer Clare MacKichan was used to old-style, bullying managers, but Cole was different. Besides having good taste, he could handle people. “If he didn’t know what he wanted, he would wait until you produced something he did want,” MacKichan told interviewer Michael Lamm. “And if he didn’t like something, he was pretty nice about it. He wouldn’t get all excited and make a big fuss.”

The ’55 Chevy was a smash, selling 1.7 million cars. The Chevy V-8 went into the Corvette next and suited it like honey on a biscuit. Cole rose to division manager and had a free hand to create another car, the 1960 Chevrolet Corvair. And that car would put him on the cover of Time magazine. “If I felt any better about our Chevy Corvair, I think I’d blow up,” he said. It was an unintentionally portentous remark. The compact had an unusual layout, with the small engine placed in the rear—like the Volkswagen. Although initial sales were strong, problems crept in. Micromanaging and cost-cutting by GM’s executive committee had contributed to the Corvair’s tendency to spin out.

As Cole became GM president in 1967, he faced even more controversy and scandals. An engine-mounting problem in other Chevy models resulted in the unprecedented recall of 6.7 million cars. Beyond this, safety, fuel economy, and emissions controls were emerging as top priorities. Some fun went out of the business, and Cole was concerned about the effect on engineers and innovation: “They will be afraid to death to do anything out of fear it might be wrong.”

A month after retiring from GM, Cole appeared on The Phil Donahue Show to debate Ralph Nader, whose exposé, “Unsafe at Any Speed,” was the Corvair’s undoing. When the two-hour broadcast wrapped, Cole shook Nader’s hand, saying, “Give me a little credit from now on. I showed up.”

Nader taunted back, “You got the lead out of gasoline. Now how about getting the lead out of GM?” It was a little rude, but Cole was out of the game by then anyway. Decades later, we remember him for his 18 patents, dynamic leadership, gregarious personality, and the motto: “Kick the hell out of the status quo.”

Ronald Ahrens’s first magazine article was 40 years ago for Soap Opera Digest. His contributions to the much-lamented Automobile Magazine spanned a 32-year period. Nowadays, he’s on a 15-year run with DBusiness (“Detroit’s Premier Business Journal”). Ronald lives near Palm Springs, Calif., where he struggles to understand desert gardening.