Born and raised in Silicon Valley, Sophia Nguyen Eng was poised for success in the technology world.

She was good at what she did—growth marketing campaigns for startups and Fortune 500 companies—and was well on her way up the corporate ladder. She founded an organization, Women in Growth, to support other women working in the tech space. Hers was a resume that would make any aspiring professional envious.

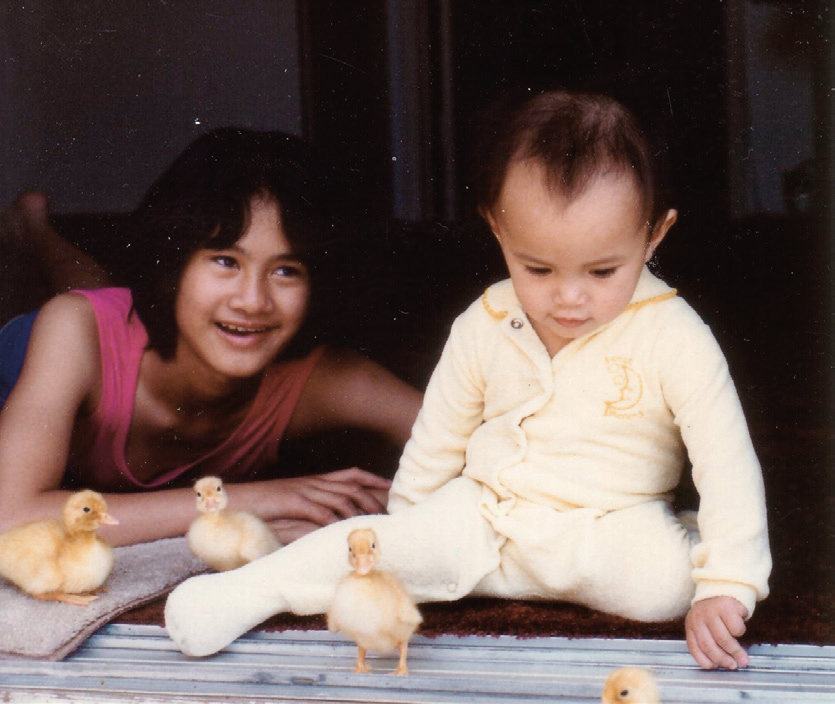

Then the birth of her oldest daughter, Emily, in 2011 inspired her to reach new heights—not in tech, but in the kitchen. It’s the beginning of this unusual and fascinating tale of how an ambitious American family traded the boardroom for a farm.

Reaching for Ancient Wisdom

Ms. Eng’s journey began at the grocery store, where the selection of baby foods looked gray and unappetizing. A first-generation Vietnamese American who wasn’t accustomed to cooking fruit, she decided to research how to make her own applesauce for Emily.

A line in a cookbook gave her pause. Organic is best for babies, it said, because their bodies cannot tolerate or process pesticides and herbicides.

“At what point can her body process it?” Ms. Eng mused. “Or are we doing it wrong, and should we be changing the way we think about food?”

It was then that she remembered the yellow book on nutrition gifted to her by a fellow military family when her husband, Tim, was an officer in the U.S. Army. The family lived on a homestead, had a dairy cow, made their own medicinal tinctures, and homeschooled their eight children. They often shared wisdom with the couple.

“She was telling me, ‘You’ve got to try this grass-fed raw milk,’” Ms. Eng recalled, laughing at the memory. “I thought, ‘Oh no. This is how I’m going to die.’”

But the responsibility of raising a child, and her own intuition, were driving her to seek out the truth about food. Suddenly, she felt that knowing the habits of this odd but healthy and happy family was vital to her own. The new mother was older and wiser, and she knew that different didn’t equate with detriment. Not to mention her firsthand experience: Growing up, she was teased for the homemade—and sometimes pungent—ethnic food in her brown bag lunches, while peers devoured processed food from brightly colored packages. Back then, she was envious of the vending machine snacks in their lunch boxes.

Ms. Eng dusted off the book: “Nourishing Traditions: The Cookbook That Challenges Politically Correct Nutrition and Diet Dictocrats.”

Written in 1995 by Sally Fallon Morell, the cookbook is based on Weston A. Price’s 11 dietary principles that emphasize eating real, unprocessed traditional foods. Price, a Canadian dentist, traveled the world in the 1930s, studying isolated indigenous cultures that had not yet been industrialized. He found a strong correlation between their traditional diets and better dental and overall health. The common characteristics from his findings, known as the Wise Traditions principles, include no refined ingredients; choosing traditional animal fats over industrialized seed oils; enjoying lacto-fermented condiments and beverages; and balancing nutrient-dense foods from both land and sea animals, including organ meats, eggs, raw dairy, and fish.

Like others before her, Ms. Eng was captivated by his work. The book gelled with her experiences with healing that came on the heels of dietary changes. In one instance, her husband’s fiercely itchy eczema disappeared when they changed their meat source from supermarket beef to grass-fed and grass-finished beef from a local farm.

It also resonated with her heritage: the rich Vietnamese flavors and traditions that influenced her parents’ wholesome, nutrient-dense cooking and sparked her own lifelong interest in nutrition. She recalled something that her grandfather, who spoke rarely, told her as a child: “Eat to live. Do not live to eat.” So began a journey following a trail of breadcrumbs that would lead her back to her roots.

RECIPE: Vietnamese Chicken Noodle Soup (Pho Ga)

(This is a short preview of a story from the March Issue, Volume 4.)