The Smithsonian Magazine labeled 1968 as “The Year that Shattered America.” It seemed that each evening, Walter Cronkite began the CBS Evening News with reports of marches; protests; bloody clashes; and even assassinations happening across the world, in our nation, and in cities not too far from home. It was in the late summer of that year that Vilna, a foreign exchange student from Venezuela, entered my former high school—Monroe County High, in Monroeville, Alabama—a small school located in south Alabama. It was probably the worst time for a young high school girl from a foreign country to come to study in the United States, in the South, and especially in the Deep South.

In Monroeville, the fear of potential racial unrest ran down the streets like syrup spreading on a dinner plate. Old men who met to play Dominoes on the town square gathered more to hear the news of what was happening in Clausell Quarters than to play their favorite game. They also whispered how Nelle Harper Lee’s book had just stirred the pot for upheaval in the town. Although her book “To Kill a Mockingbird” had been published five years earlier, the blame for some of this agitation, they surmised, could certainly be placed at her feet for bringing attention to their hometown. The locals knew that Maycomb was a fictitious name for Monroeville.

I, however, was more interested in knowing why my former high school was chosen as the host school for a foreign exchange student. Monroe County High School wasn’t noted for its superb programs of study or for its state-of-the-art facilities. What was the appeal to the committee of the international study program? Surely, other schools in the South or even in Alabama could put their best foot forward to host foreign students.

If I was puzzled about the choice of Monroe County High School, I was totally baffled when Miss Norris, the faculty sponsor of the new International Exchange Program, asked Mother and Daddy to help host Vilna on weekends during her year of study. We didn’t even live in the city limits of Monroeville. Our little community was six miles away from town. Our family vacations took us to the Great Smoky Mountains and Florida beaches—not international destinations.

Maybe Miss Norris knew that in our small, rural community of Mexia, our home was the “welcoming center” for newcomers to Mexia Baptist Church and that our house was the central hub of activity for our unincorporated, rural town. Mother hosted more showers, club meetings, and social events at our home than most country clubs. So, it wasn’t surprising that Sherry, my sister who was a senior like Vilna, asserted her fine-tuned hospitality skills in welcoming her wholeheartedly into our home.

I knew that my sisters and I would learn much about Vilna’s culture as a result of her stay, and we did. However, it was my parents’ quiet and out-of-step actions from their normal routine that revealed lasting lessons for life.

In the 1960s, our family could have been considered as the model family for Southern Baptist home life. Daddy’s fingerprint was on all aspects of church service at Mexia Baptist Church—deacon, trustee, chairman of numerous church and associational committees, and teacher. Mother served in almost every role allowed to women in the denomination. If the church doors were open, my sisters and I were there. It was against this religious backdrop that Vilna, a devout Catholic, crossed the threshold into our Baptist world.

In our young, unworldly minds, the word “Roman” implied foreign and strange, and certainly all things Catholic were in direct opposition to Baptist doctrine. Leading up to the 1960 presidential election, Daddy and Mother were adamant that they would never vote for John F. Kennedy, because a Catholic president would “take orders from the Pope.” Mother and Daddy were asked by the Bethlehem Baptist Association in Monroe County to serve as delegates to the Southern Baptist Convention in 1960 when then-presidential candidate Kennedy addressed the convention with these words: “But if this election is decided on the basis that 40 million Americans lost their chance of being president on the day they were baptized, then it is the whole nation that will be the loser in the eyes of Catholics and non-Catholics around the world, in the eyes of history, and in the eyes of our own people.” What was the impact of those words on my parents’ political views? Who did they cast their vote for in the election? Vilna’s stay at our home lends me a clue. Out of respect for Vilna and her religious heritage and culture, Mother and Daddy, the staunch Baptists, drove Vilna to and from Monroeville every Sunday so that she could attend Sunday Mass, thus altering their own worship routine drastically.

Advances in technology over time have erased some of the ordinary ways of living in ways we can now take for granted. In 1968, to call a friend who lived just 25 miles away meant a long-distance charge was added to the monthly phone bill. I didn’t call home but once each week from college because of the additional charges, but Daddy and Mother never said no when Vilna requested to call her parents in Venezuela.

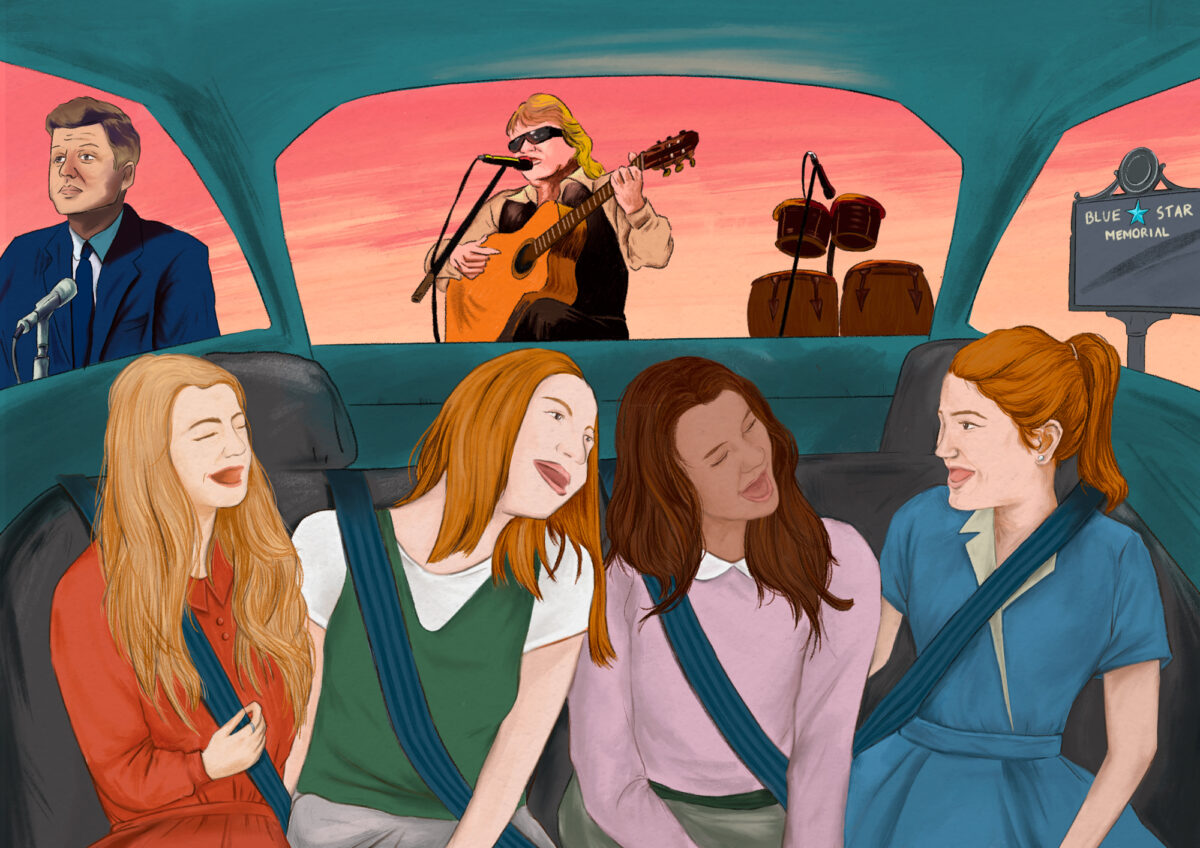

Vilna’s interest in Alabama history resulted in the family and Vilna taking short road trips to visit historical sites on Saturdays. Like a choreographed routine Ginger, Sherry, Debbie, and I would pile into the backseat of our Buick, while Vilna sat up front between Mother and Daddy. Daddy would pull the car off the road at every Blue Star Memorial marker in Monroe County, and each stop became a history lesson not only for Vilna, but also for us. History books and local lore tell of the ghost town of Claiborne, which is located only five miles from our home. The only evidence of this once-thriving city of 5,000 people are the graveyards that sit on bluffs above the Alabama River. When we stopped the car and walked among the crumbling tombstones, the inscriptions told a haunting story of the massive toll of the Yellow Fever pandemic of 1873. Grandmother Jaye had often told us stories of how our great-grandmother had attended the glorious gala given to welcome Marquis de Lafayette to Alabama at the Masonic Lodge in Claiborne. As we toured the building, which had been moved up the bluff to Purdue Hill to escape the swampy waters that bred the carriers of death that caused the pandemic, we could almost see the ladies swirling and twirling to the music as they enjoyed welcoming the handsome and noble Frenchman to their new state of Alabama. The faded and almost forgotten images of Claiborne, the ghost town, came alive to us that day.

When the local radio station in Monroeville announced that Jose Feliciano was going to perform at Auburn University in Auburn, Alabama, Sherry wishfully asked if Vilna and she could attend the concert. Surprisingly, Mother and Daddy agreed, and even more shocking was that they would let Sherry, a 16 -year-old, drive 150 miles to Auburn. As Sherry took control of the wheels of the car, it rolled along toward Auburn with two teenage girls singing loudly to the music of the Spanish-born performer. When Jose climbed the steps onto the stage playing his acoustic guitar and singing “Light My Fire,” Sherry still recalls Vilna’s expressions of joy. “She was in heaven, pure heaven.”

My parents’ actions of welcoming Vilna to our home revealed some universal truths that connect us all. It’s what you have to offer, rather than what you have, that matters. Religious divides aren’t as big as they appear. And let hospitality permeate your actions, for it’s the essence of following the great commandant of “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

Gwenyth McCorquodale has been teaching since the age of 7, when she taught her three younger sisters the letters of the alphabet. Gwenyth retired from Judson College in Marion, Alabama, where she served as professor of education and head of the department of education. She has written books, articles for national and international journals, and for her hometown newspaper The Monroe Journal.