Gary Cooper is synonymous with the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was one of its most successful box office draws. He was nominated five times for the Best Actor Oscar and won twice for “Sergeant York” and “High Noon.” Handsome, strong, and with an honest stare, Cooper became the country’s model of masculinity, integrity, and courage.

His roles were varied. They ranged from military heroes, like Alvin York, the most decorated U.S. soldier in World War I, and Billy Mitchell, considered the Father of the U.S. Air Force; to a Quaker father in “Friendly Persuasion”; the tragic baseball player Lou Gehrig in “The Pride of the Yankees”; and a tamer of the Old West, none better known than the fictional Marshal Will Kane in “High Noon.”

Maria Cooper Janis, the daughter and only child of Cooper and Veronica Balfe, recalled her father saying that he wanted to try to portray the best an American man could be. These dignified and masculine roles surely captured the ideal, but they also captured something else. Janis said the man that millions of moviegoers saw, and still see today, was, in so many ways, playing himself.

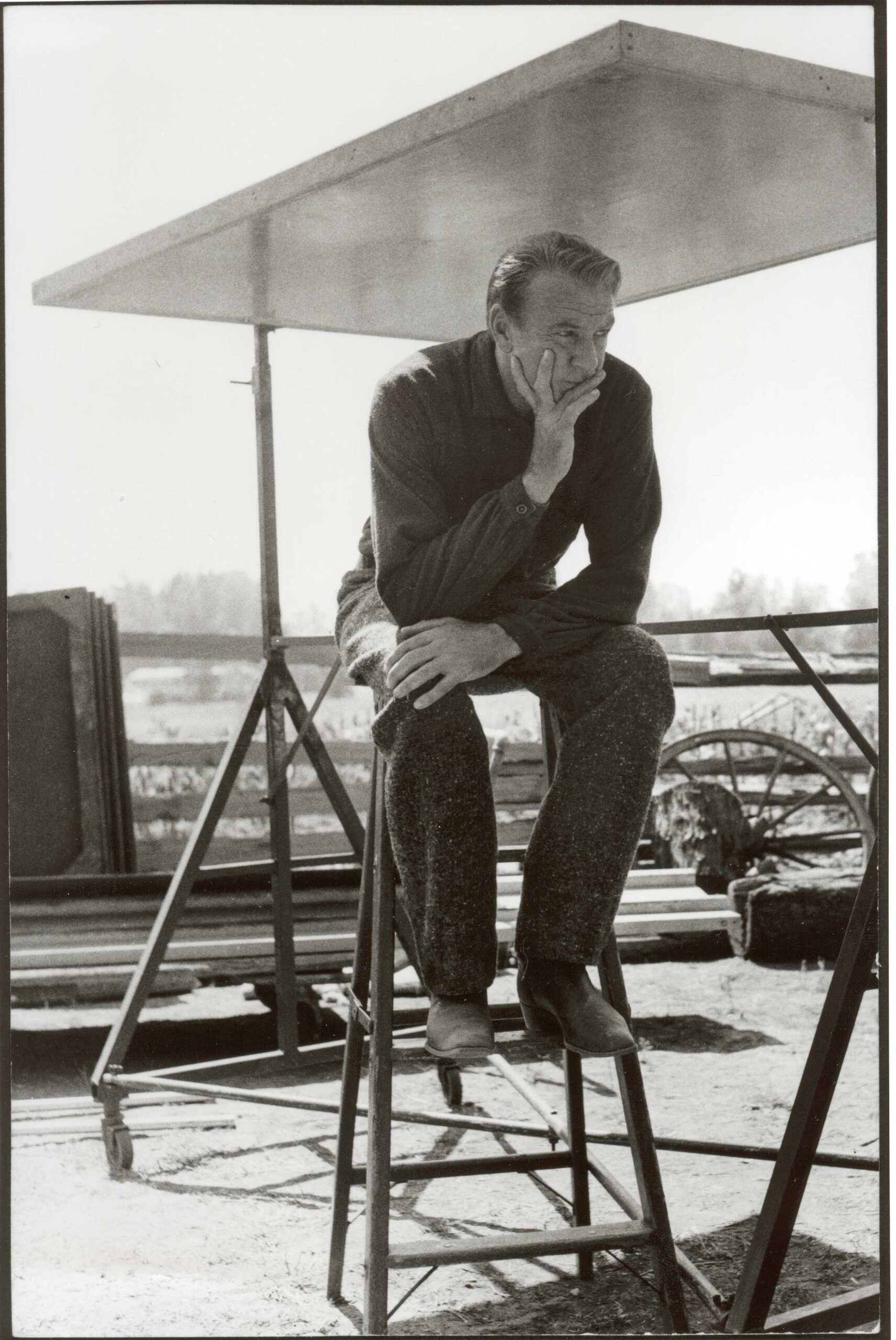

Rugged and Sophisticated

From the rough-and-tumble Western stereotypes to the sophisticated man-about-town, he was “as comfortable in blue jeans as he was in white ties and tails,” she said.

There is a famous photo called “The Kings of Hollywood” of Cooper standing alongside Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, and Van Heflin in their white ties and tails, cocktails in hand, having a laugh. It is the elegant and sophisticated version of Cooper—the quintessential image of Hollywood’s leading man. Indeed, Cooper was one of the kings for several decades.

But he was also an everyman. Cooper grew up in early 1900s Montana. He was born in Helena just a few years after it was named the state’s capital. It was a rich town despite being part of the recently settled West. It was an environment―both rugged and luxurious―that Cooper would go on to personify.

Janis said her father’s first friends were the local Native Americans. They taught him how to stalk and hunt animals and perform his own taxidermy. His friendships helped him understand the plight of the Indians. His father, Charles Cooper, a justice on the Montana Supreme Court, had long been concerned about the Native Americans.

“My grandfather was always working for the underdog,” she said. “My father must have heard a lot of those stories. [My father] always felt he should defend those who needed defending, especially those who didn’t have the clout or standing to win.”

The Defender

Cooper found himself defending others on film and in real life, and sometimes those two mixed. Although he stated before Congress that he was “not very sympathetic to communism,” he was sympathetic to those in Hollywood―actors, writers, and directors―who were targeted by the Hollywood blacklist movement. One of those with whom he was sympathetic was Carl Foreman, who had written the script for “High Noon” and had refused to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. After “High Noon,” Foreman left for England, where he would write “The Bridge on the River Kwai.”

“My father was actually very close to Carl Foreman,” Janis said. “My father told Stanley Kramer [the producer], ‘If Foreman’s off the picture, then Cooper is off the picture.’” Foreman remained, and Cooper performed one of his most definitive roles as a marshal who stands against a criminal gang in a town where everyone is too afraid to help. “High Noon” is believed to be a representation of the Hollywood blacklist era―a belief that Janis holds as well.

“My father passionately believed you were free to believe what you wanted to believe,” she said. “He was threatened that he would never work in Hollywood again. But he knew what he believed and he lived his life.”

Lessons From Cooper

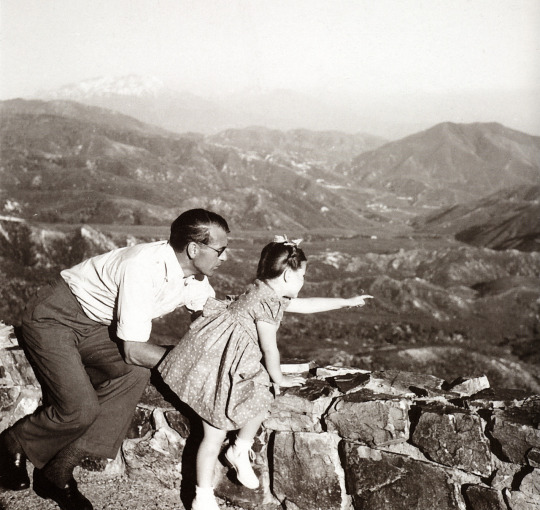

Cooper kept working in Hollywood for nearly a decade more until his tragic death from cancer. But Janis wants people to know that there was so much more to her father than his time on the big screen. It is one of the reasons she wrote her book “Gary Cooper Off Camera: A Daughter Remembers,” which focuses on his family life.

“We had a very close family bond,” she said. “If you have loving parents who show you discipline, that’s a leg up in life. I think the importance of a loving, strong father figure for a girl is excruciatingly important.”

Her mother and father were both a source of encouragement. Despite growing up the daughter of Gary Cooper, she never felt pressured to go into acting.

“He basically left it up to me. He and my mother were very realistic. I came to my own conclusions about what I wanted in my life,” she said.

She studied art at the prestigious Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and began a successful career as a painter. She said that being an artist was apparently in her DNA, as her father, her grandmother Veronica Gibbons, and her great-uncle Cedric Gibbons, who designed the Oscar statuette, were gifted artists.

Cooper―at home and on-screen―had given his daughter the proper perspective of what she should look for in a husband. He had thoroughly educated her on the fact that there were some men who “don’t act very gentlemanly.” So he taught her boxing and self-defense.

“He told me, ‘Don’t let any man intimidate you. You are going to be a beautiful woman. Stand up for yourself,’” she recalled. “It was enough to give me a sense of confidence.”

When her father died in 1961, she continued her career in art and retained that confidence. In 1966, she married another artist, Byron Janis, one of the world’s greatest classical pianists. She said marrying Janis was “the greatest fortune that could have ever happened to me.” The two celebrated their 57th wedding anniversary this April.

In Cooper’s Memory

Although Cooper has been dead for more than 60 years, his legacy remains. That legacy has been entrusted to his daughter’s care. She has worked to champion her father’s causes as well as his name.

Janis established a scholarship at the University of Southern California in Cooper’s name for Native American students who wish to pursue an education in film and television. She also advocates for continuing research into the terminal illness of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), famously known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

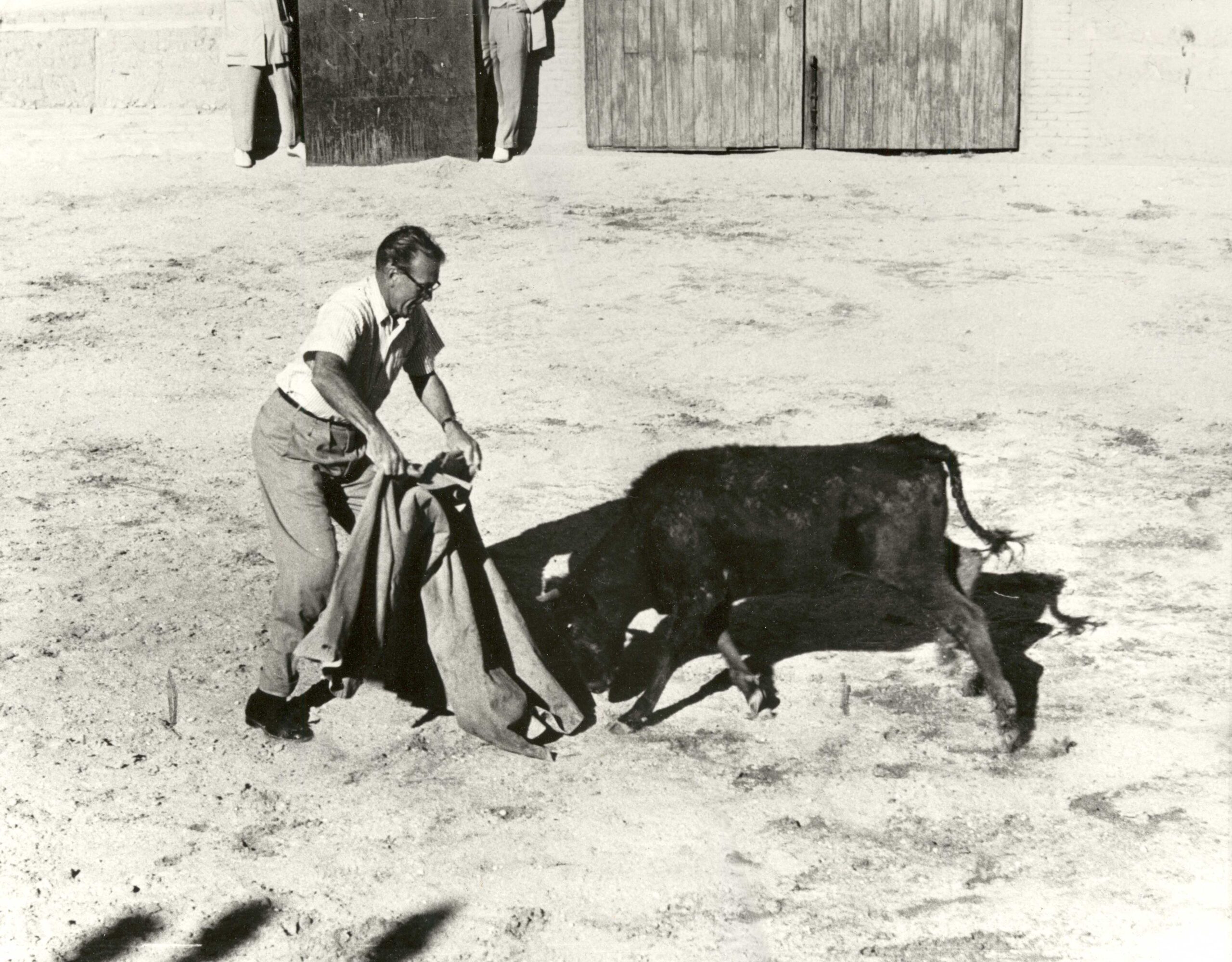

Along with her book, she collaborated with Bruce Boyer on his book “Gary Cooper: Enduring Style” and contributed to the documentary “The True Gen,” about Cooper’s friendship with Ernest Hemingway. She also established the official Gary Cooper website dedicated to his memory.

Janis said she has understood her past and that of her father’s better over the years, quoting the Danish theologian Soren Kierkegaard: “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” In a broader sense, her efforts are to ensure Gary Cooper will be better understood by all as the years go by.

From Aug. Issue, Volume 3