Historic New England is the largest regional heritage organization in America today. Founded in 1910, it was the earliest organization of its type with a focus on the preservation and continued use of properties of historic significance. Historic New England aims to educate the public on their archives and collections and engage in public outreach by establishing house museums—working with homeowners and communities to protect buildings and landscapes.

With a collection of over a million records of photographs, homes, paintings, objects, sculptures, and documents, Historic New England has been able to tell the most complete story of how New Englanders lived from the 17th century to today. There are over 6,500 works of fine art housed across the New England states. Recognizing the importance of their collection, and to engage with the public, “Artful Stories” has brought together works from ten different house museums as well as a number of works from Historic New England’s storage.

The exhibition is held at the historic Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts—a jewel of late-19th-century American architecture built in 1878. The estate was designed by William Ralph Emerson, prominent American architect and cousin of transcendentalist American philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. Not only was Emerson of the eponymous family, he was a close friend of leading Boston painter William Morris Hunt, and he collaborated with American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. It was a time of cultural renaissance in America, when bronze foundries produced full-scale works on American soil for the first time, and the cities were filling with Neoclassical architecture.

Curated by Nancy Carlisle (Historic New England’s Senior Curator of Collections) and Peter Trippi (European art historian and editor-in-chief at Fine Art Connoisseur), “Artful Stories” explores regional stories told through art. Rather than simply showcasing Historic New England’s best paintings and sculptures, the curators selectively chose artists, portraits, and settings to give the artwork and theme a larger sense of context. As Carlisle noted, the experience of curating a show like this reveals new information every time you scratch at the surface of history.

The exhibition was well planned, but just as society had to contend with the pandemic lockdowns, so did “Artful Stories.” They quickly pivoted to online programming and immersive 360-degree videos. Karla Rosenstein, the site manager of the Eustis Estate, shared that “from the beginning, we had planned to utilize the interactive touchscreens to add extra multimedia materials to ‘Artful Stories,’ so we luckily had already been developing some online content for the exhibition.” As it became clear that they would not be able to open up as scheduled, they wanted to provide an online preview that was a full version of the exhibition. “While working from home, we created a far more robust version than we had initially planned” added Rosenstein.

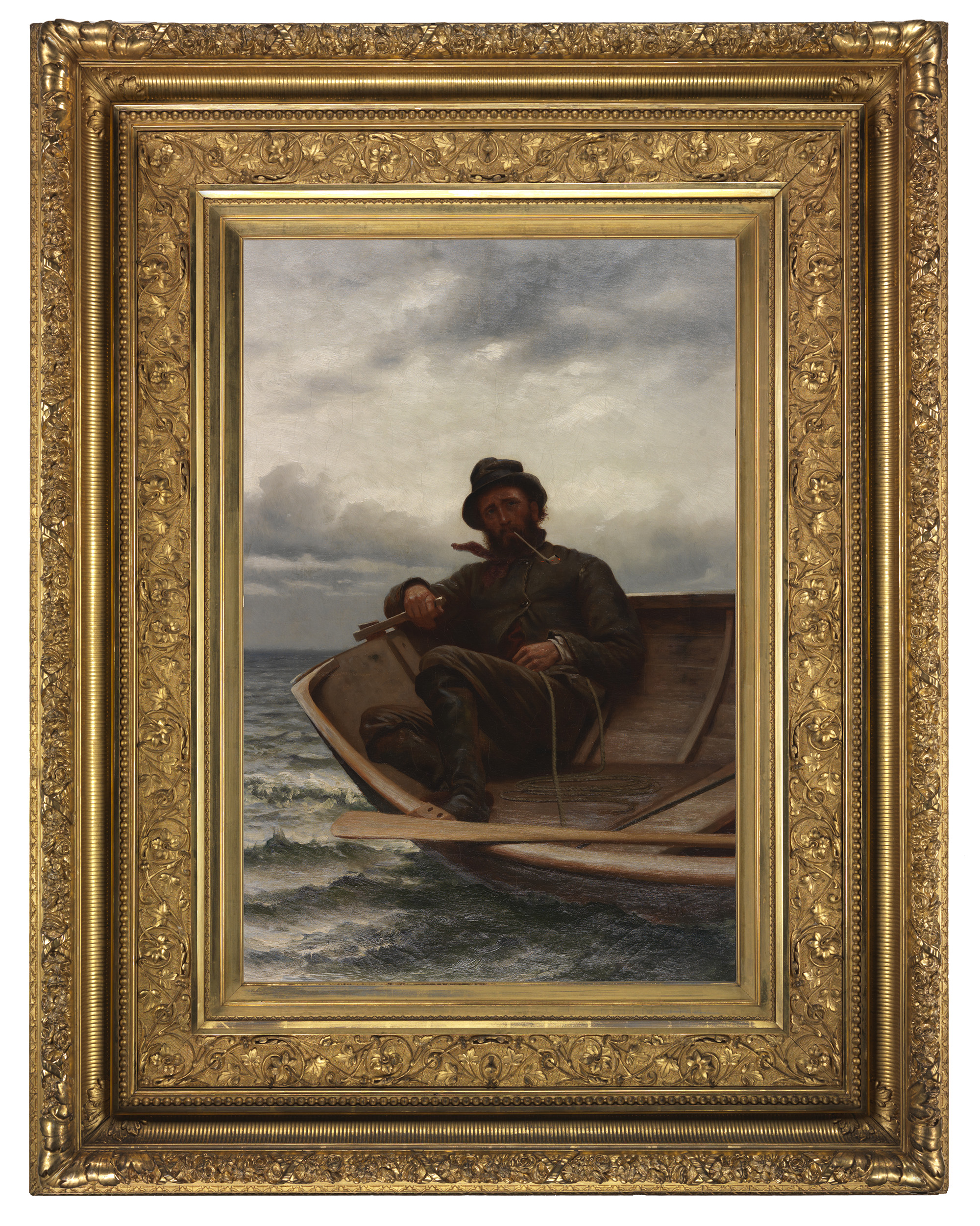

The curators chose to present the works in a variety of themes across four galleries. The first gallery, “Land & Sea,” is a survey of the historical geography of New England. The second gallery, “At Home in New England,” showcases how and why the people of New England came to settle there, while the third gallery, “New England’s People,” reveals the cast of characters involved. The fourth gallery, “Wide World,” is about how the New Englanders interacted with people and places outside their region.

Unlike other exhibitions that would source works from outside their collection, Rosenstein noted, “it was very fortunate that this show was entirely from Historic New England’s collection as we did not need to negotiate date changes with other institutions.” The gallery was open to in-person visits in October 2020 and welcomed small groups of visitors to enjoy the exhibit. “We had a good number of members eager to attend it and get back into our museums,” added Rosenstein. “We also found ways to pivot our planned programming online and hosted a series of conversations between the curators and scholars, artists, and other curators that was attended by far more people than we would have expected in person.”

The show is full of interesting distinctions—a striking, perfect copy of Vigée LeBrun’s self portrait was a surprise for Carlisle. “The copy of Vigée’s portrait was by Elizabeth Adams, an artist about whom we knew nothing. During our research, we discovered who she was and the lengths she went to receive professional training.”

As our collective American [MISSING NOUN] shifted so much throughout 2020, this allowed the curators to examine some of the asymmetries of the past, confronting the history of race and social class through the lens of today. Two such landscape paintings are hung in the first gallery, “Land & Sea.” One painting is a tight, Hudson-River-School-influenced panorama by the son of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, while the other is a pure Barbizon, Romantic landscape by an African-American barber who had to strive for his training as a painter. On these two paintings, Peter Trippi noted “the contrast between the landscapes painted by Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow and his neighbor (on the wall), Edward Mitchell Bannister—what different life journeys they had, but they both ended up being talented painters flourishing in New England at the same time!” Truly, one of the most important aspects of representational painting is its ability to transcend setting and social class and rely on truth, skill, and beauty.

Throughout the show, there are a number of thoughtful arrangements and connections made that came to light through their research. In gallery four, “Wide World,” there is a wall which showcases not only the talent and skill of the artists, but the ingenuity and distinction of the American art patrons during the late 19th century. One is a portrait painting of Richard Norton by Italian artist Antonio Mancini. Hanging next to it is Edward Burne-Jones’ portrait of Sara Norton, Richard’s sister. These two paintings couldn’t be more stylistically distinct; Edward Burne-Jones was a Pre-Raphaelite, a classicist in the truest sense of the word, and Mancini an innovator, regarded by American artist John Singer Sargent as the greatest living painter of the time.

The simple fact that these two now hang side-by-side in contrast to each other displays the power of patronage—allowing the artists to fully express their vision of the subject, rather than attempting to impose their own aesthetics onto their likeness. This is further driven home by their accompanying painting on the wall, “St. Servan Harbor” by Edward Darley Boit. Best remembered as the patron who commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint his four daughters (housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston), Boit was also an accomplished painter in his own right.

Throughout the exhibition, there are multimedia opportunities to learn more about the various artists and subjects. For those residing outside of New England, the website offers one of the most complete possible viewing experiences online. “Artful Stories” is both a truthful retelling of the Northeast’s history and an important chapter in cultural preservation, which Historic New England continues to champion. The exhibit has been extended until October 17th, 2021.