“I once shook hands with Pat Boone and my whole right side sobered up,” the actor and singer Dean Martin once said.

Call it the “Pat Boone Effect.”

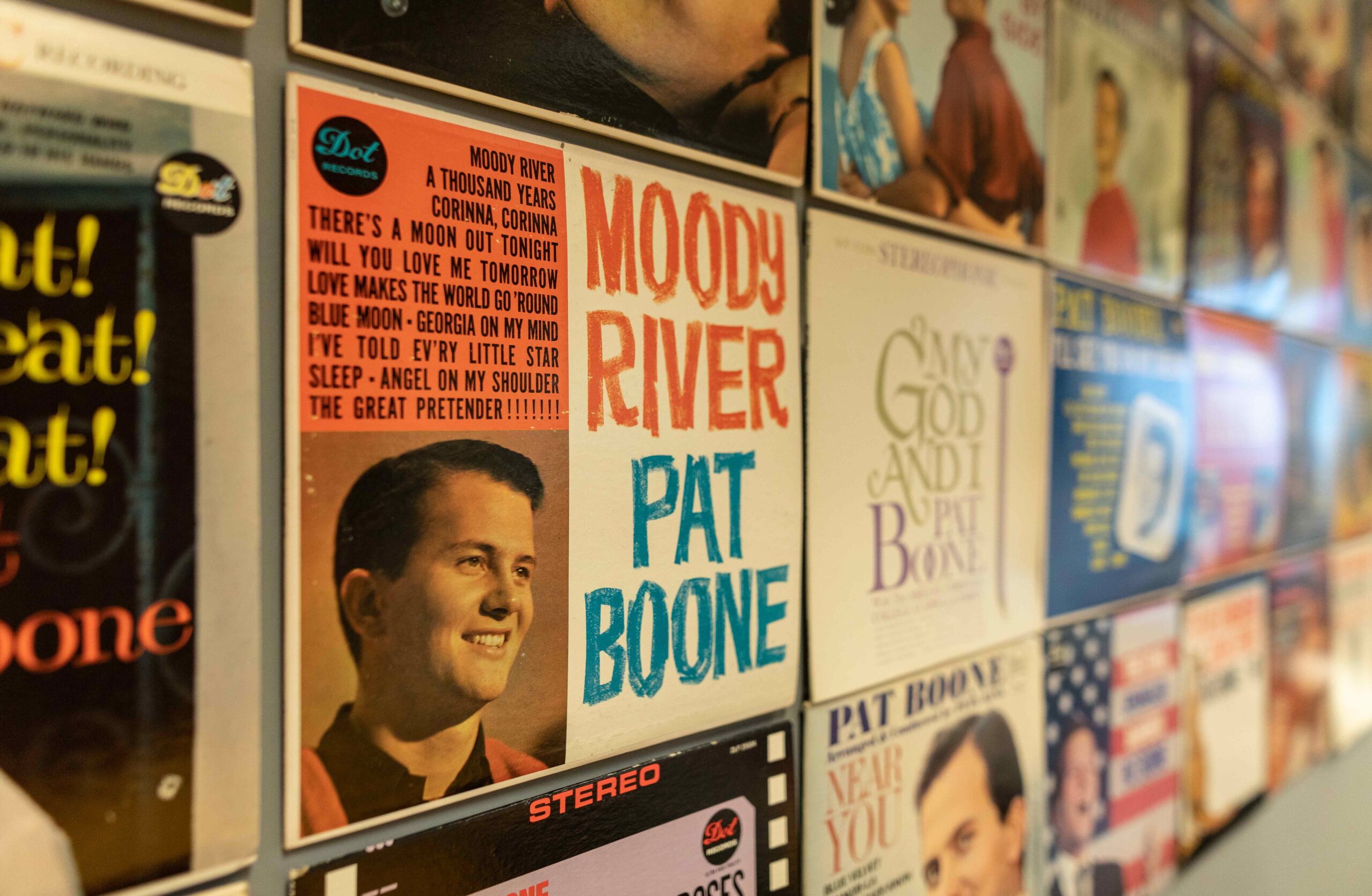

Example: In 1997, hard rock and heavy metal were at their peak. Their sound was the epitome of doom, their lyrics the essence of defeat. Enter an artist from the ’50s and early ’60s, with 38 Top 40 hits to his credit, a singer known for tuneful songs, sung in the smoothest possible way—the very antithesis of hard rock/heavy metal—Pat Boone.

The album, “In a Metal Mood: No More Mr. Nice Guy,” featured Boone’s crooner vocal stylings against a lush background of big band saxophones and brass sections. A complete deconstruction of the hard rock/metal genre, “In a Metal Mood” uncovered surprising melodic richness in such unlikely sources as Ozzy Osbourne, AC/DC, Alice Cooper, and Deep Purple. Boone’s version of Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water” married the song’s opening guitar riff to a salvo of trumpets, while Boone’s heartfelt delivery gave new life to the dismal lyrics.

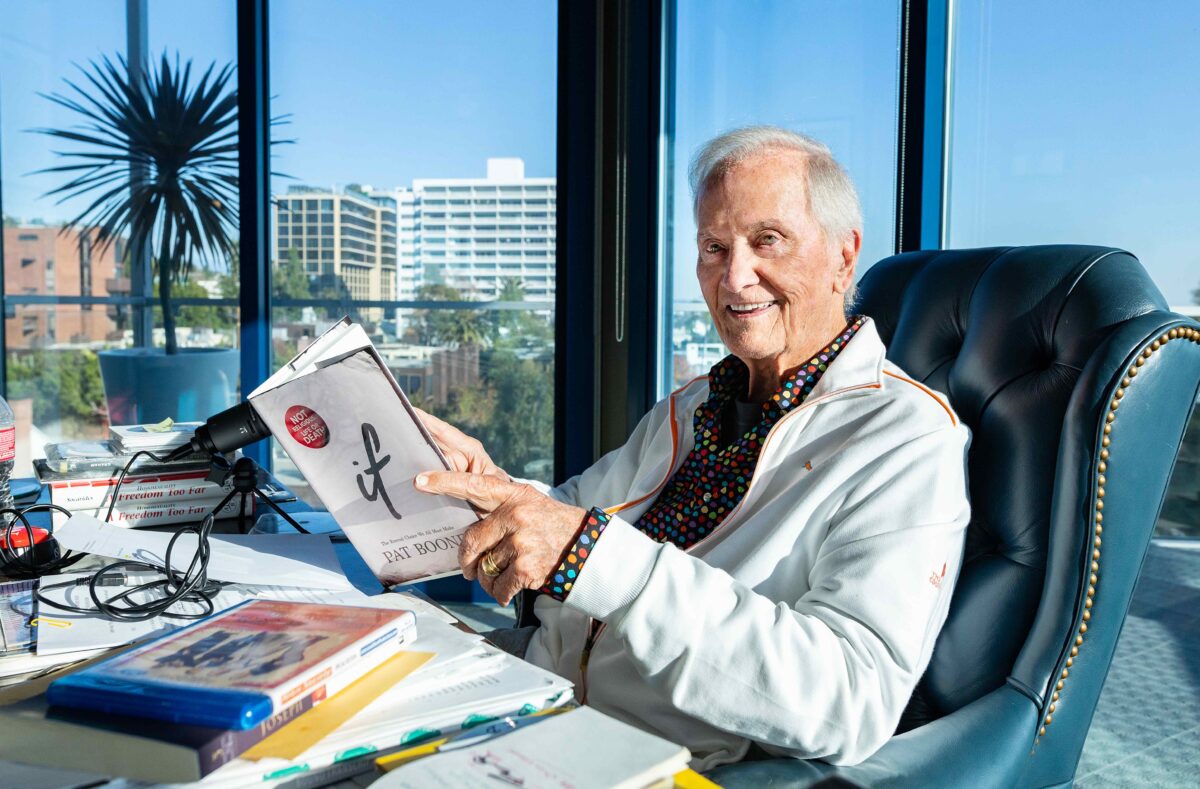

Heavy metal didn’t have a chance against the “Pat Boone Effect” and its founding creed: Everything, even the onset of the darkest conditions, can be resisted and tamed. The “Pat Boone Effect” continues today, as its namesake writes books, makes movies, and finds new songs to sing at the age of 88.

An Icon of the ’50s

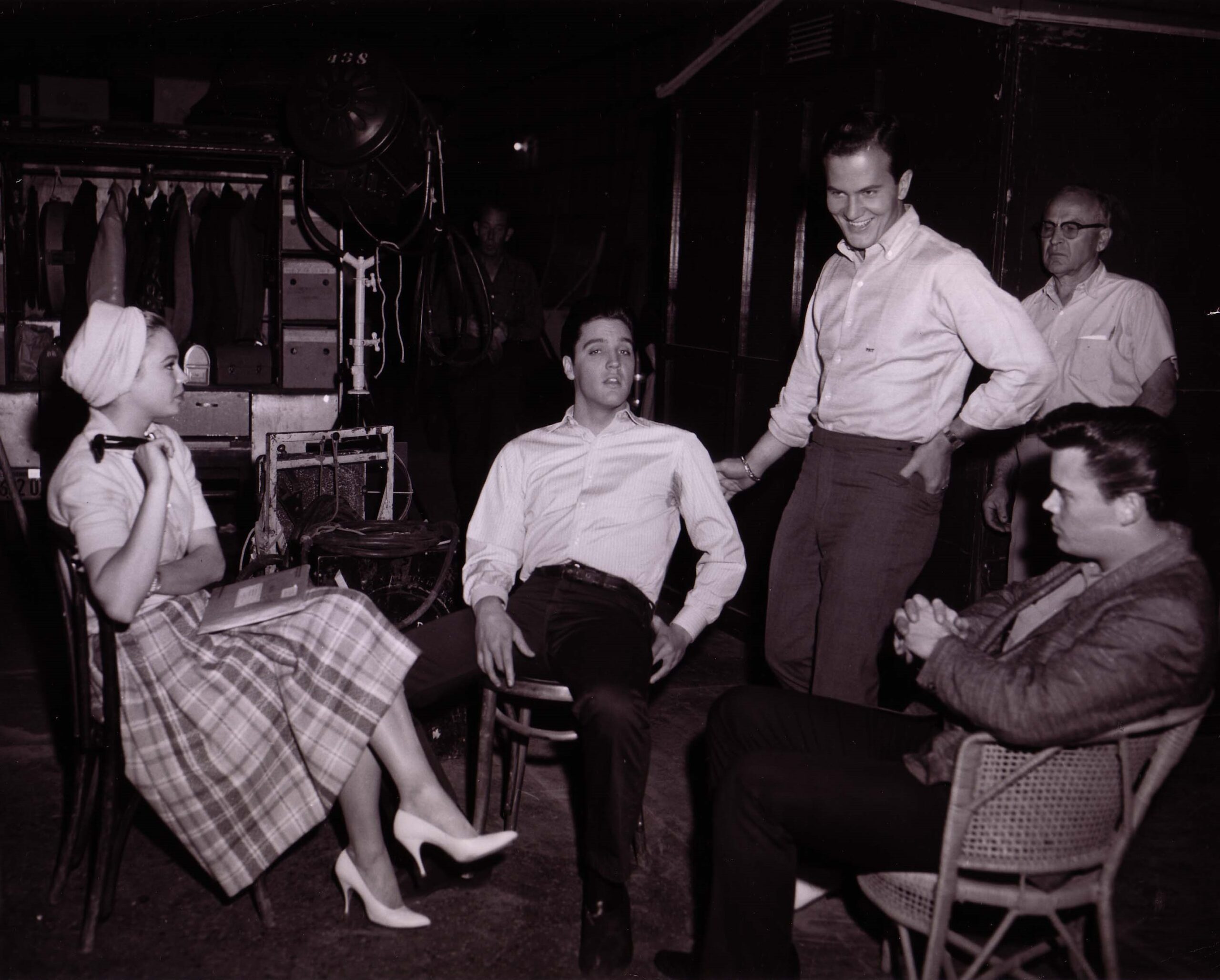

Pat Boone was long ago a name to speak in the same breath as Elvis Presley. In the ’50s, the two of them vied for the top of the pop charts, with Boone often winning. A writer for Time Magazine extolled the young phenom dressed in white shoes in a 1956 article: “Pat Boone, 22, was just another hillbilly singer from Nashville 18 months ago. Today, nobody who hears him in person ever hears the first or last few robust notes—they are always drowned in squeals of bobby-sox delight.” In addition to recording those 38 Top 40 hits between 1955 and 1963 (13 of them gold singles), Boone acted in more than a dozen movies, including “Journey to the Center of the Earth” and the 1962 remake of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “State Fair.”

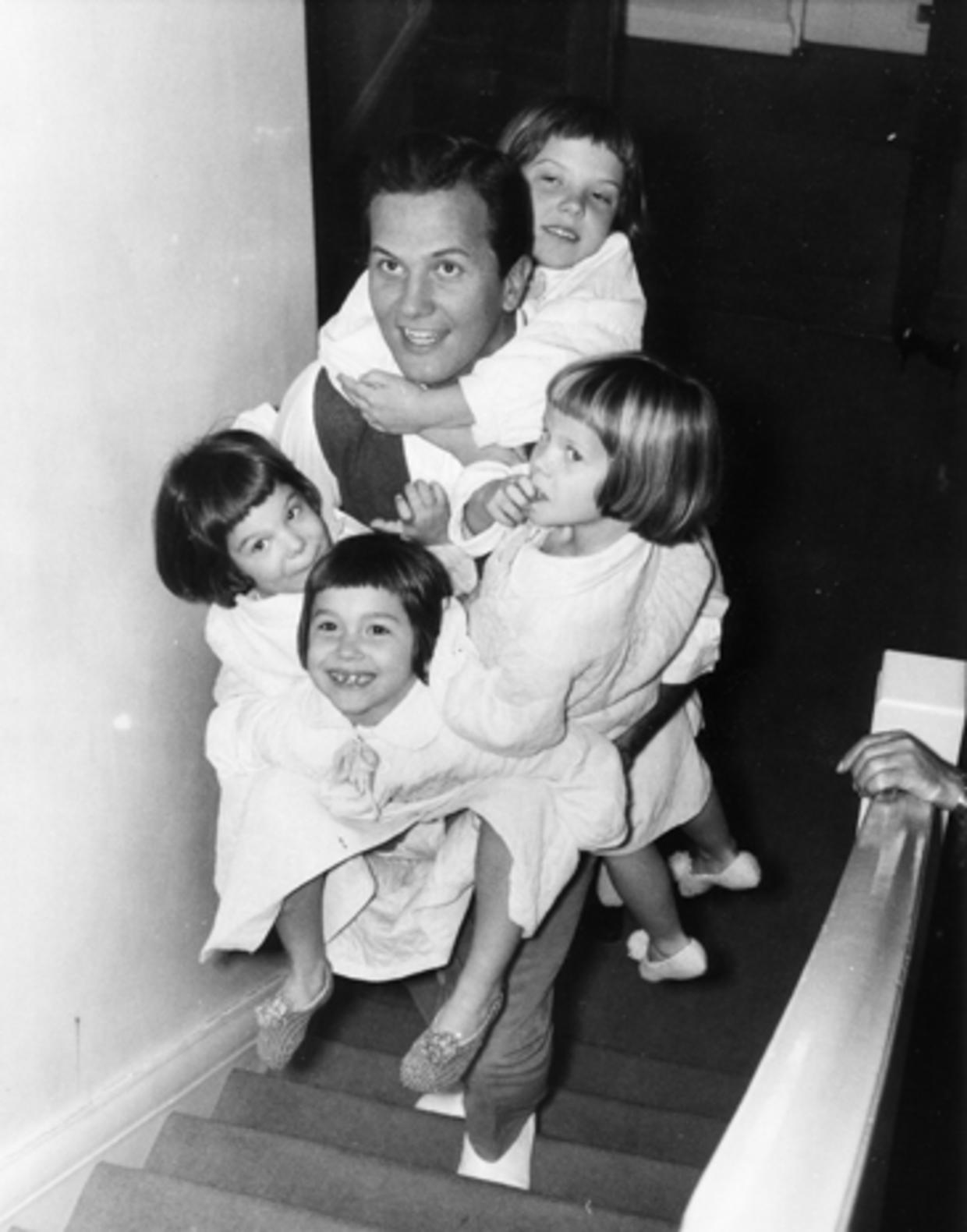

Along the way, he exemplified a pristine image of restraint and hard work. In a lecture to young people, Boone once warned that “kissing for fun is like lighting a lovely candle in a room full of dynamite.” Unwilling to exploit what he assumed was temporary fame, Boone got his bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1958, the same year his biggest single hit, “Love Letters in the Sand,” came out, with the intent of becoming a teacher. But fame persisted, allowing him to marry his sweetheart, Shirley, who would be his wife for more than 60 years until her passing in 2020.

And then—the world stopped turning and commenced to spin in the opposite direction. In 1964, the year Boone turned 30, the British invasion brought the Beatles and the Rolling Stones to American shores, and in their wake, a striking change in the cultural weather.

“Drugs and promiscuous sex,” Boone answers immediately to the question, “What prompted the cultural changes of the mid- to late ’60s?” Whatever it was, the change meant that Boone’s milk-and-cookies image suddenly became yesterday’s newspapers. So he moved on, never changing his beliefs nor his singing style, and never judging the new wave (he called Alice Cooper and John Lennon friends), but persisting. He continued to perform and record, finding an audience just outside the one that surfed the mainstream, while tilting occasionally against contemporary culture in a semi-humorous mode that kept one second-guessing: Was he serious about those metal covers, or was that an elaborate joke to expose the thinness of the material? Boone never quite gave a straight answer.

Grounded in Faith

Boone’s latest enterprises, “If: The Eternal Choice We All Must Make,” a book-length essay on his lifelong spiritual beliefs, and “The Mulligan,” a faith-based movie that follows up on his recent acting appearances in other faith-based movies, confirm his dedication to the same values that first made him famous.

“The word ‘if’ is of utmost importance. ‘If’ you believe. ‘If’ you choose. ‘If’ you act,” Boone said of his book’s theme. The book guides the reader in navigating choices that Boone insists “are not religious, but matters of life and death.” He said he felt compelled to write it. “I even designed the cover, which looks like the burned edges of a piece of paper, with the single word ‘if’ in the middle,” he added, to convey the feeling of urgency. The choices as answered in the book lead the reader to the Christian faith that Boone has held from childhood.

“The Mulligan” likewise explores his faith, from the standpoint of second chances: “A ‘mulligan’ in golf is a second chance, so why not a second chance in life to correct the mistakes we all make? It’s a gospel theme with a secular plot, set on a gorgeous golf course.” The film was released in select theaters in April 2022.

Boone’s faith has led him to feel an urgent need to bring Christianity and Judaism together. “One of the biggest mistakes ever made was dividing the Bible into Old and New Testaments. It’s a single testament. One part needs the other.”

Boone’s regard for Judaism and his empathy for Israel once led to an especially demanding challenge. On Christmas Eve, 1960, Boone sat listening to the musical theme to “Exodus,” a film based on Leon Uris’s novel about the founding of the modern state of Israel. It wasn’t just for pleasure. The piece was wildly popular due to an instrumental version by the piano duo Ferrante and Teicher, but it had no lyrics, and without them its significance as a paean to Israel’s founding was blunted.

Several lyricists had tried and failed to fit meaningful words to composer Ernest Gold’s soaring melody. Now, the task was given to a popular singer with deeply Christian beliefs. Could he do it? Boone wasn’t even principally a songwriter. His biggest hits were written by other people: “April Love” was penned by a professional songwriting team for the 1957 movie of the same name; “Ain’t That a Shame” was a Fats Domino cover; and Boone’s biggest hit of all, “Love Letters in the Sand,” was a neglected ballad from 1931.

“I sat listening to the music over and over and I told Shirl”—his nickname for his wife—“nothing was coming to mind. Then I just heard the first four words: ‘This land is mine.’ I grabbed a Christmas card on a nearby table and started to write.”

Finding the first four words opened up the floodgates of creativity. “God gave this land to me,” and the rest of the lyrics, crowded onto the back of the Christmas card.

“It’s like a second national anthem in Israel,” Boone said. “The director of Yad Vashem,” which is Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, “asked if I would will the original manuscript of the lyrics to them. I said, ‘You can have it now, but it’s on the back of a Christmas card.’ They were fine with that.”

A superstar in his 20s, and a persistent figure in entertainment ever since, Pat Boone goes on believing that the bad in the world can be, must be, overcome. The Pat Boone Effect could do the world a world of good.

From April Issue, Volume 3