One could say that philanthropy is good for the nation and good for the soul.

In fact, philanthropy is a key component permeating the backbone of America’s success: American communities have benefited from private initiatives long after the benefactors have passed on.

Such is the case with one of America’s most beloved innovators: Milton S. Hershey. The wealthy industrialist invented legendary chocolates known the world over. However, Hershey’s legacy of philanthropy started with a belief in moral responsibility to others in need. “What good is money unless you use it for the benefit of the community and of humanity in general?” he was quoted as saying.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1857, Hershey had experienced hunger and poverty throughout his youth. Although loved, Hershey was accustomed to a routinely absent father. With limited choices, he left school at 14 and began a series of apprenticeships; he found success in the candy making industry 12 years later with his own business, Lancaster Caramel Company. It was his thriftiness, ingenuity, and hard work that placed Hershey in a position to give back. After selling his caramel business for $1 million in 1900, he made plans to build the Hershey Chocolate Company near where he grew up in Derry Church, Pennsylvania. There, he could mass-produce affordable, yet delicious, milk chocolate candies; create employment opportunities for others; and utilize the rich, creamy products from the dairy farming community.

Without heirs, Hershey and his wife Catherine dedicated their lives to philanthropic opportunities through the creation of the Hershey Theatre, the Hershey Amusement Park, and the Hershey Industrial School. The latter started out as an orphanage on the old homestead in the early 1900s. Today, Hershey’s legacy lives on as thousands of students have benefited from attending the well-endowed Milton Hershey School (as it is now known), a cost-free, private school for boys and girls from low-income families. As a home and school, MHS covers 100 percent of the cost of medical, dental, and psychological care, housing, clothing, food, extracurricular activities, and more for its students, allowing them to focus on their personal growth. This year’s enrollment consists of 2,000 students.

Josh Kelly, like so many students before him, comes from an adverse background. Students who experience neglect, poverty, or negative environments apply for free admission and find themselves on a new path of opportunity. Kelly, a bright senior who hails from Philadelphia, plays ice hockey, works as a lifeguard at the school’s pool, and plans to further his education in the field of business or finance after graduation.

“When I was younger, my dad was never around. I was getting into trouble because I didn’t know how to express my emotions of anger very well,” said Kelly of his time as a troubled 1st grader. He and his older sister arrived at Milton Hershey School to get away from home and school dilemmas. Upon arrival at the Milton Hershey School, Kelly credits his elementary school houseparents for their tremendous influence on his emotional growth and well-being.

“They always push you to do better because they want you to succeed,” he added. “I didn’t have parent figures, so to speak, so they really set me up for a better future.”

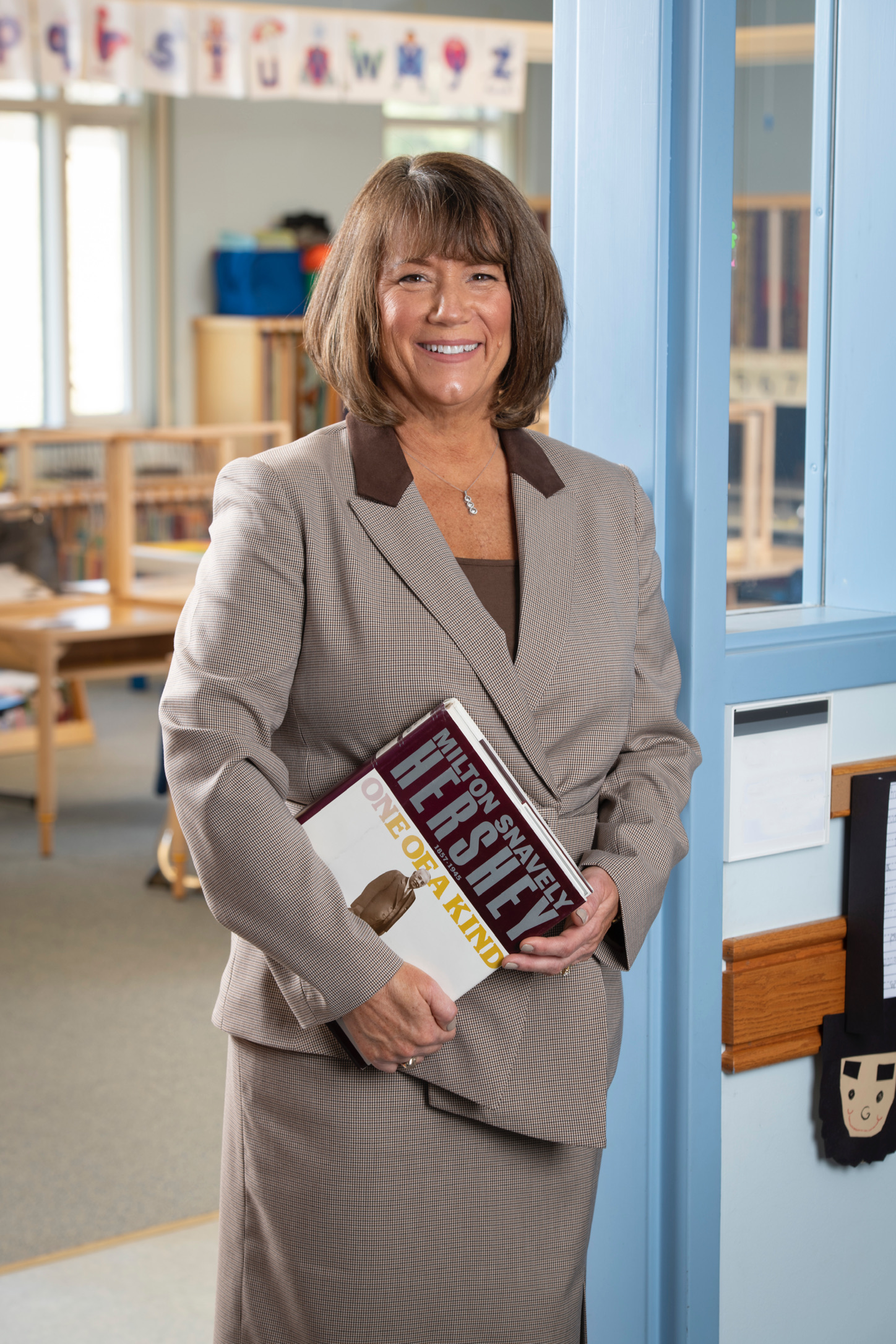

A better future, asserts School Historian Susan Alger, is why Hershey’s visionary ideals led him and Catherine to contribute to and support an institution like no other—a private establishment that not only educates but offers support and balance in family life.

“Students can relate to Milton Hershey’s story, who experienced a meager existence in a dysfunctional family. He wanted students to be useful citizens with stability,” Alger explained. “He just always said he wanted to get away from the idea of institutions and give them a happy life.”

In the beginning, Hershey’s Industrial School was an all-male enterprise. Aside from studies, everyone helped with daily chores, from gardening to milking cows. And the school grew in numbers. Being completely self-contained with truck patch farming, the students and employees grew everything they needed.

After Catherine Hershey passed away in 1915, Milton Hershey endeavored to be more involved in all aspects of the school’s success, providing opportunities in trades for students and financially ensuring needs were met.

According to Alger, his direct involvement of care and concern for the school was essentially fatherly. Being a bit sentimental and shy, Hershey would take boys for rides in his car and visit their student homes. Hershey was quoted as saying, “If we had helped a hundred children it would have all been worthwhile.”

Even during World Wars I and II, the school continued its deliberate mission to educate youth from troubled homes. Originally, the Deed of Trust allowed boys ages 4 through 8 to attend if the father was deceased; however, about the time of the Great Depression, the age restriction expanded to ages 4 to 14 with either mother or father deceased. Even when enrollment was down during World War II, it was due to those who chose to serve. “Close to 1,000 served, and we annually honor our Gold Star alumni who gave their life to service,” Alger stated.

While other philanthropists, in their generosity, give away partial or complete estates after their passing, Hershey was different. “He gave the bulk of his entire wealth while still alive,” Alger said. With the success of the Hershey Chocolate Company, Hershey quietly and humbly transferred the entirety of his company’s shares in 1918 to the school. But this fact was not known until a few years later.

With heart and will bent toward benevolence, Hershey was motivated by his own upbringing but also motivated through innovation.

“I wanted to get away from the idea of institutions and charity and compulsion, and to give as many boys as possible real homes, real comforts, education, and training, so they would be useful and happy citizens,” he said of his school. “Most of them [students] have better chances for character building and education than ever before. Perhaps they don’t have the chance to make as much money as some individuals have made, but they will lead to happier lives.”

Historical records and oral histories indicate that Milton Hershey was a fair man. “He always gave the benefit of the doubt. As a problem solver, he wanted things to be right and ethical. He wanted people to live honestly.”

And unlike his contemporaries, she added, Hershey was grounded. As an example, in comparison to other wealthy philanthropists like the Fords, Wrigleys, and Vanderbilts, Hershey built a modest yet graceful home, High Point Mansion.

And though Hershey passed away in 1945, his innovative school continued to cultivate an education that helped hundreds of students. In 1977, the founder’s original dreams expanded, admitting girls from disadvantaged homes or tragic backgrounds.

“My dad tragically died when I was 4 years old,” said Christine Cook, a recently retired kindergarten teacher of 35 years at the Milton Hershey School.

Cook remarked on her own journey as the first female to graduate.

“I arrived in 10th grade as a sophomore from Philadelphia. We were taught intangibles—to work hard and to be kind. And we were taught tangibles like milking cows at 5:30 in the morning on the coldest of winter days or in the middle of the summer with temperatures soaring above 100 degrees. This is good, character-building stuff.”

Even if students didn’t like the chores, it was part of the overall experience. But Cook admits she was fortunate. Other students came from families with tragic, even abusive, backgrounds. Leaving family behind and starting fresh can be extremely challenging for the students and their families.

“I remember it being difficult for my mother. It was a tough decision, but a great one. So many parent supports exist today that help families experiencing feelings of guilt, […] giving up their children even though the school provides them with better opportunities,” Cook continued.

She would know. Before Cook graduated as the first alumna in 1981, she had played field hockey, basketball, and softball. She was a member of the school’s band, earned a spot in the National Honor Society, and held positions in student leadership. She graduated from college and returned to the school to teach the hallmark values, ideals, and integrity so instilled from her own experiences at the school. Cook believes that if Milton Hershey were alive today, he would be impressed by the vast majority of alumni who have successfully graduated and are employed in solid leadership positions. The school’s alumni have surpassed 11,000.

Cook was named the Alumna of the Year in May 2021, and she attests to the amazing honor of being a student. Her experiences led her to contribute in many ways to countless others who came through her classroom. In fact, she taught just under 500 students over her 35-year tenure.

“Hershey’s idea of success was making your mark in society in a positive way. A successful person is one who helps others. Hershey was big on helping the other guy, making the world a better place,” Cook added.

When her students graduate, she makes a point to stay in touch with those who are considered “Lifers”—having attended from kindergarten through their senior year. For the seniors, she invites them over to her house, cooks a homemade meal, and breaks out photos to share memories. When a Lifer graduates, she makes sure her congratulatory card includes a copy of his or her kindergarten report card.

“As you graduate, you understand the needs of the kids; it makes you work harder. I would tell my kindergartners that they attend the best school in the whole wide world.”

These kids are the lucky ones because no other school subscribes to what Milton Hershey stood for, she added. He left a mark in the world and lived up to his words.

The philanthropic mission of Milton Hershey has been good for the students and employees. As School Historian Alger put it, “There’s one quote of Milton Hershey that sums up what he wanted, and it’s what we still do today: ‘One is only happy in proportion as he makes others feel happy and only useful as he contributes his influences for the finer callings in life.’”

It’s an adage that Kelly appreciates. Every year, he and the other students become philanthropists of sorts. With community service days, they learn to give back, too. He appreciates the opportunities awaiting him after graduation, thankful for the founder he never met who helped turn his life around.

If Milton Hershey’s philanthropic success continues from within the hallways of his hometown private initiative, it will be good for America, for his legacy of education lives on with students long after they graduate. One could say his gratefulness and generosity echo beyond the grave: “I hope to see the school carry on to new heights. After a man dies, he cannot spend his money, and it has been a pleasure for me to spend mine as I have done.”