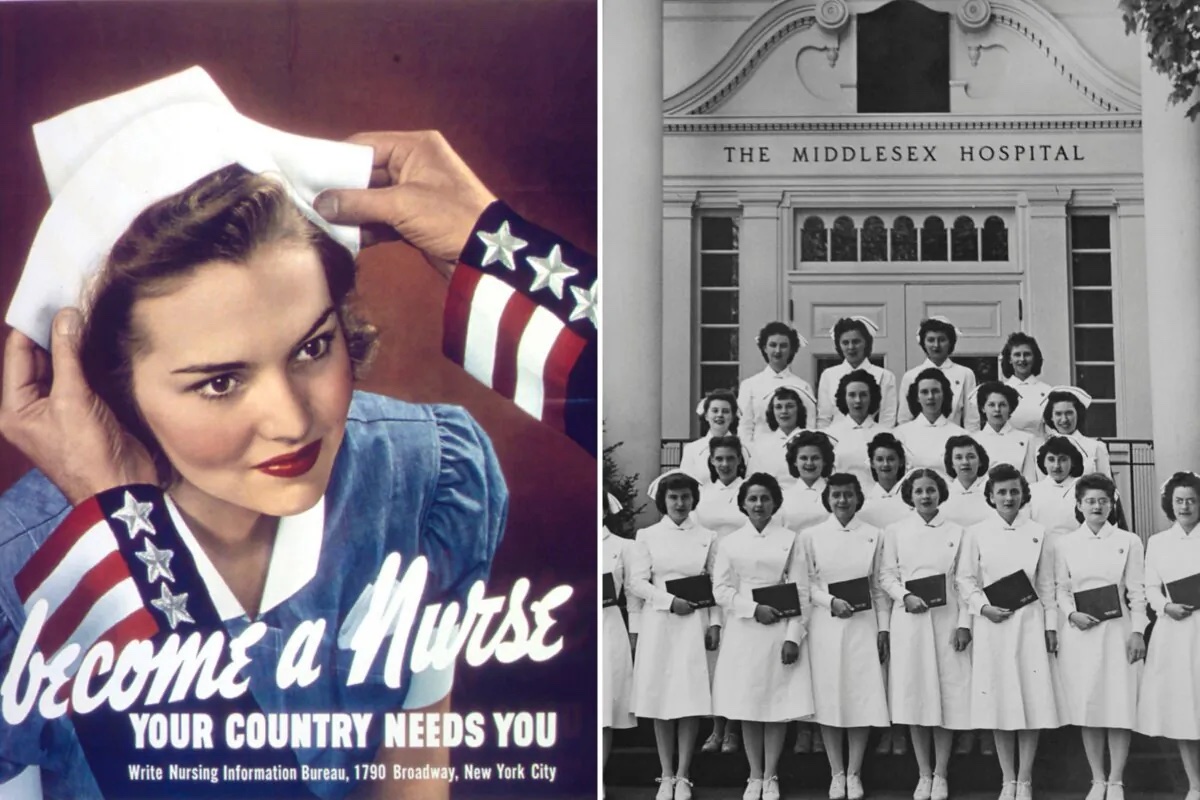

Mention “Rosie the Riveter” to anyone who’s familiar with America’s entry into World War II and you’ll likely get a smile.

Bandana-wearing “Rosie” was the star of a ubiquitous poster in a national campaign aimed at recruiting women to fill jobs in America’s industrial plants after male laborers enlisted in the military. The campaign paid off, with hundreds of thousands of women going to work in America’s factories.

But while “Rosie” remains a fictional character that gained widespread publicity, there’s another group of real-life heroines who supported the war effort and who even today are much less known.

Before the United States entered World War II, the United States Public Health Service had forecast a shortage of nurses stateside, raising important questions as war loomed: Who would fill the void left by civilian nurses who had joined the military? Who would care for the injured soldiers returning home from battle? And who would tend to sick civilians hospitalized across the country?

The answer was the more than 120,000 women who served in the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps.

Nurses to the Rescue

Nurses to the Rescue

The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps program was signed into law by Congress in 1943 with two goals: improving the quality of training at existing nursing schools, but also attracting women from 17 to 35 years old who would receive tuition scholarships in exchange for completing 30 months of training and agreeing to work as a nurse, for as long as the war lasted.

From 1943 to 1948, when the program concluded, nursing schools were transformed as federal funds shaped more modern facilities and paid for newer laboratory equipment. At the same time, program graduates gained valuable knowledge that would ease the deficit of nurses and which could be used in a postwar setting, widening a pool of dedicated nurses for years to come.

Armed with newfound classroom training and given opportunities to learn the ropes at hospitals affiliated with the corps, cadets served in military hospitals, VA (Veterans Administration) hospitals, private hospitals, public hospitals and public health agencies.

In an interview with American Essence, Alexandra Lord, chair of the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, called the program “brilliant in its approach.”

“Nursing schools were not consistent in how they were teaching nurses and providing an education,” Ms. Lord said. By transforming and strengthening existing nursing schools while providing women with free tuition tied to a pledge of future service, a steady source of cadet corps members would be available to work in hospitals across the country.

“The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps has been highly successful,” then-Surgeon General Thomas Parran Jr. testified before the House Committee on Military Affairs back in 1945. “Our best estimates are that students are giving 80 percent of the nursing in their associated hospitals. … The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps has prevented a collapse of the nursing care in hospitals.”

Many of the cadets hailed from preexisting nursing programs that served Navajo, black, and mixed student bodies, in keeping with the Bolton Act’s mandate that there be no racial or religious discrimination in the program. The edict was a milestone at a time when even the military had not fully embraced integration. Yet discrimination did rear its head, as when hundreds of black nurse corps members were assigned to work in less desirable conditions, at stateside camps holding German prisoners of war.

Tough Conditions

Shirley Wilson, now 99 years old and living in Connecticut, applied to join the Cadet Nurse Corps in 1944. Shortly after her interview, her mother became critically ill with blood clots. A brother had also sustained third-degree burns after falling into a fire. While those incidents delayed her start date with the corps, both occurrences deepened her sensitivity to the need for quality medical care. But long hours and pressing demands took their toll. While delivering a glass of water to a hospitalized patient, “he looked at me and he died,” Ms. Wilson told American Essence. Performing hospital duties on the same day as cadet corps classes, Ms. Wilson asked herself, “Am I in the right place?” After completing her mission as a cadet, Ms. Wilson joined the U.S. Air Force as a uniformed military nurse who served stateside during the Korean War and went on to teach cardiac nursing at rural hospitals.

Nurses around the country faced different challenges beyond the long hours (sometimes having 12-hour workdays), such as scarce supplies, and in the case of cadets at the University of Washington School of Nursing, a polio epidemic that hit Seattle in the 1950s.

Nurses around the country faced different challenges beyond the long hours (sometimes having 12-hour workdays), such as scarce supplies, and in the case of cadets at the University of Washington School of Nursing, a polio epidemic that hit Seattle in the 1950s.

Industrial production in support of the war effort also contributed to the workload that weighed down nurses; with more factory workers getting injured, the workload of nurse cadets increased. Andrew Kersten, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Cleveland State University, cites the Bureau of Labor Statistics data detailing 2 million disabling industrial injuries annually from 1942 to 1945.

Postwar Service

Beatrice Strauss joined the Cadet Nurse Corps in 1947 and worked at the Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn in New York. Like Shirley Wilson, she wasted little time in deciding what to do after the program’s demise. She attended graduate school, earned a master’s in rehabilitation nursing, and later served as a nursing supervisor for a foster care program with more than 1,200 children in need of help.

She served during the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “We would get infants into care who had been born to drug-infected women who had ‘some kind of infection,’ and after about three months in care, many of our babies would become seriously ill and die.” Eventually, experimental medications were developed. “It was so gratifying to see that after a while some of our little babies were growing up to be toddlers!” Ms. Strauss wrote in one of many personal profiles posted at www.uscadetnurse.org.

Ms. Strauss’s move into pediatric infections was one of the many benefits of having nurse cadets become exposed to some specialty programs as part of their rotations at affiliated hospitals.

“Even in training, we spent three months on every [type of] service in the hospital,” said another corps graduate, Emily Schacht, age 97, who lives with her daughter in Connecticut.

In recognition of the contributions that nurse cadets made to the war effort, a bipartisan bill honoring women who served in the corps was introduced in Congress in May 2023. The U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps Service Recognition Act, if enacted, would recognize former cadets with “honorary veterans” status, a service medal, burial plaque, and other privileges. It would not provide still-living nurses with pensions, healthcare benefits, or burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

“There was no official discharge. The war ended and they [cadets] just went on. … They are the only uniformed members of the war effort that has yet to be recognized,” said Eileen DeGaetano, Emily Schacht’s daughter and herself a retired nurse.

Rep. Mike Lawler (R-New York), one of the eight original sponsors of the bill that is working its way through both chambers of Congress, stated that the bill would “honor the vital work of cadet nurses during World War II, provide them the honors they are due, and forever enshrine their legacy in the collective memory of our nation.” The bill has been referred to the House and Senate committees on veterans’ affairs.

A Mother–Daughter Bond

Ms. DeGaetano said the influence of her mother’s time in the Cadet Nurse Corps is “woven throughout the fabric” of her own nursing career.

“I learned to work hard and never to compromise the care I was providing by cutting corners. I learned to solve problems and create solutions without optimal conditions or resources. … I found the courage to stand up to the status quo and advocate for my patients,” she said.

“And perhaps, most importantly, I learned to measure the success of my career through the knowledge that my efforts made a difference in someone else’s life.”

From March Issue, Volume IV