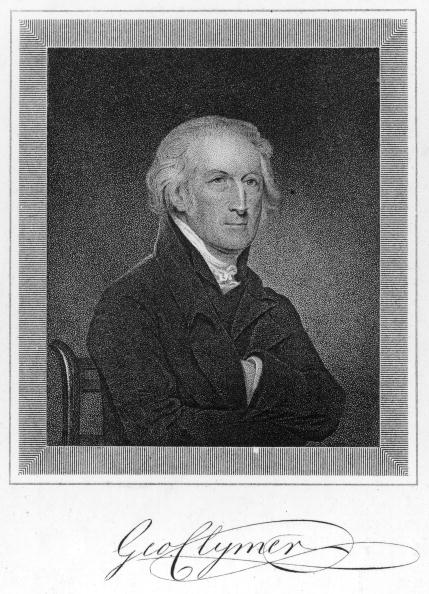

By the time George Clymer was 1 year old, both his mother and his father were dead. Orphaned, George was placed in the care of his Philadelphia uncle, William Coleman. Coleman was an extraordinary man—a lawyer and merchant of Quaker stock, a friend of Benjamin Franklin (and member of the latter’s Junto), a founder with Franklin of the American Philosophical Society and the University of Pennsylvania, and a leading philanthropist. In his “Autobiography,” Franklin described Coleman as possessed of the “coolest, clearest head, the best heart, and the exactest morals of almost any man I ever met.” And fortunately for young Clymer, uncle William loved him like a son.

Clymer was educated primarily in the extensive personal library of his new benefactor, where Coleman often found the lad poring over some tome or another. Clymer’s favorite author was Jonathan Swift. He thus developed a predilection for learning at a young age, and before long, he had adopted “republicanism” as a political philosophy. He thus cherished liberty as defined by Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard who, writing anonymously as “Cato” in the 1720s, characterized it as:

“The power which every man has over his own actions, and his right to enjoy the fruit of his labour, art, industry, as far as by it he hurts not the society, or any members of it, by taking from any member, or by hindering him from enjoying what he himself enjoys.”

George’s education continued in his uncle’s counting-house, where he was trained in numbers—and the ins and outs of running a mercantile enterprise.

An Influential Merchant in Tempestuous Times

Clymer inherited some wealth from his grandfather in 175o. Then, with the death of William Coleman in 1769, he inherited the lion’s share of his uncle’s sizable estate as well. This was a great material blessing, of course, but these were tempestuous times. The French and Indian War had effectively removed the French from North America—but British authorities decided to leave ten thousand troops on the continent. To raise revenue in support of these troops, the various Navigation Acts—heretofore somewhat ignored—would finally be enforced, including a new set of regulations: the Sugar Act (1764). Colonists from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania had protested loudly at this, questioning Parliament’s very right to levy such a tax in the first place. Many colonials boycotted British goods.

The real uproar, however, came with Parliament’s passage of the Stamp Act (1765), which applied an internal tax on the colonies for the first time. In response, the Sons of Liberty rioted in the streets, colonial legislatures passed anti-Stamp Act resolutions, and an inter-colonial Stamp Act Congress issued a joint protest to Parliament and to the king. Clymer, now 26 years old and recently married, was among the protesting colonials. Indeed, among the Philadelphia elite, he was one of the most militant advocates of resistance to Britain.

Even though the Stamp Act was eventually repealed, Parliament immediately passed the Declaratory Act, reminding the colonists that Parliament hadn’t given up the principle that it could legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” The subsequent Townshend Acts demonstrated this, and once again the non-importation movement roared to life, crippling British exports. Clymer himself led boycott efforts in Philadelphia, at the same time authoring political pamphlets and broadsides in support of separation from Britain—a very radical view at the time. Despite the barrage of colonial opposition, Charles Townshend, the British politician who proposed the Townshend Acts, stringently enforced the acts. When the Massachusetts assembly issued an anti-Townshend circular letter, the governor dissolved the assembly, sparking mob violence, in turn precipitating the arrival of four regiments of British troops to Boston.

It was in this atmosphere that Clymer inherited his uncle’s significant mercantile business. He now had much more to lose, even as the military occupation up north produced ever-worsening relations between British authorities and the people of Massachusetts—and, by extension, those of other colonies as well. The killing of a twelve-year-old named Christopher Snider by a customs informer in Boston was the last straw, leading within a couple of weeks to the “Boston Massacre.” Troops were subsequently pulled out of Boston proper.

The Tea Act and Tea Parties

Though things seemed to quiet down after 1770, the Gaspee Affair of 1772—when a British customs schooner was attacked off the coast of Rhode Island—sparked both British and colonial outrage once more. The next year, the Tea Act was passed, favoring the British East India Company at the expense of countless American smugglers.

At 34 years of age, Clymer took charge of local resistance to the Tea Act. When the Boston rebels established a committee of correspondence with fellow rebels in Philadelphia, they particularly sought out Clymer. Clymer also played a leading role in Philadelphia’s Oct. 16, 1773 “tea meeting,” when, according to an early biographer, citizens of the city were impressed by Clymer’s “reasoning, sincerity, zeal, and enthusiastic patriotism.” The gathering produced a series of resolutions, one of which declared that:

“The resolution lately entered into by the East India Company, to send out their tea to America subject to the payment of duties on its being landed here, is an open attempt to enforce the ministerial plan, and a violent attack upon the liberties of America.”

The resolutions of the Philadelphia “tea meeting” inspired Bostonians to similar resolves. Indeed, Massachusetts man John Adams would later write that:

“The flame kindled on that day [Oct. 16, 1773] soon extended to Boston and gradually spread throughout the whole continent. It was the first throe of that convulsion which delivered Great Britain of the United States.”

That December, just days after Boston’s more famous “Tea Party,” Philadelphia held one of her own, intercepting a British tea ship. Clymer himself convinced the captain to turn around and return to Britain.

George Clymer thus helped set in motion the chain of events that would ultimately explode into armed revolution.

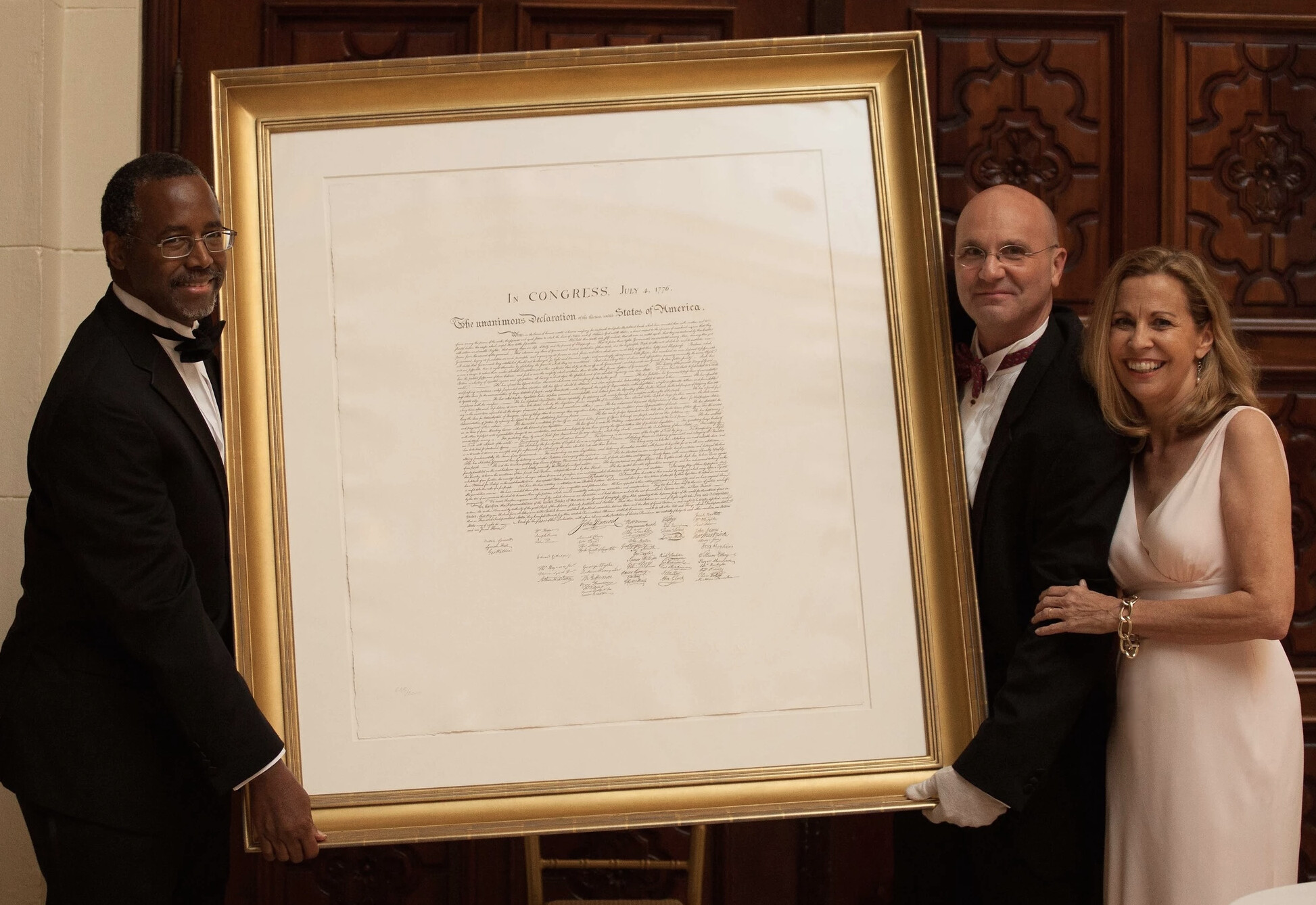

Signing the Founding Documents

After the “shot heard round the world” was fired at Lexington, initiating the American Revolutionary War, Clymer answered the call for “Patriot” volunteers, engaging the British in company with other Pennsylvanians in support of George Washington and the Continental Army. He also established a militia and helped fortify Philadelphia. Around the same time, and in a show of support for “the cause,” he poured much of his gold and silver into the Congress’s paper money, or “continentals,” eventually losing a fortune when the “continentals” were inflated into worthlessness. But when part of the Pennsylvania delegation to the Second Continental Congress rejected the proposed joint Declaration of Independence and abandoned that body, Clymer was elected to help fill their vacant positions.

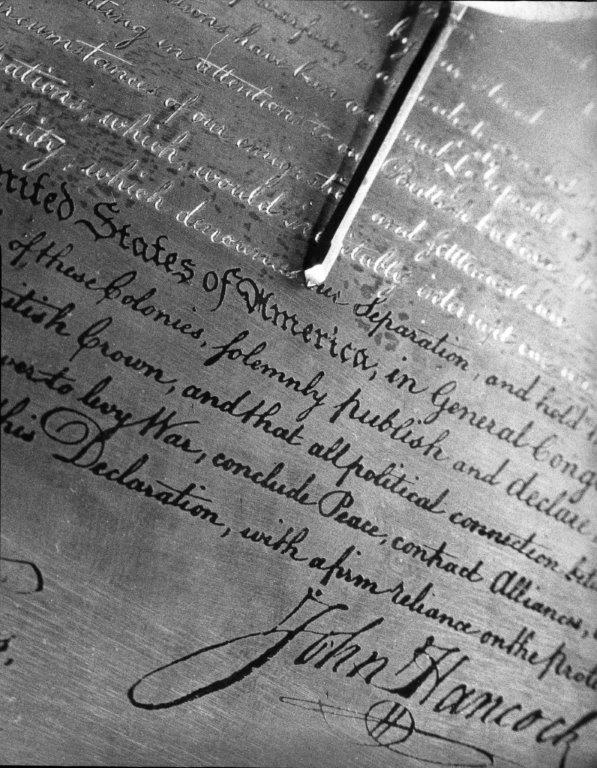

This he did—and as such, he was present to inscribe his signature onto the new confederation’s founding document, along with 55 other men. “For the support of this Declaration,” Clymer and his fellows thereby announced, “with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Clymer went on to act as a liaison between George Washington and the Continental Congress, a risky business, since it often involved covert travel across enemy territory to the front; served in the Congress for most of the war years; helped formulate Pennsylvania’s constitution; secured an alliance with the Shawnee and the Delaware; and raised vital funds for the Continental Army. After the war, he continued to work as a merchant while serving in the Pennsylvania legislature, then represented that state in the Philadelphia Convention of 1787. It was there that the Constitution was written. Clymer was a signatory.

Thus it was that Clymer became one of only half a dozen men to have signed both the Declaration of Independence and, 11 years later, the federal Constitution. In his honor, a borough and a township in Pennsylvania and a town in New York are all named after him.

Dr. W. Kesler Jackson is a university professor of history. Known on YouTube as “The Nomadic Professor,” he offers online history courses featuring his signature on-location videos, filmed the world over, at NomadicProfessor.com