“History, to me, is so easy to sell,” said Brian Kilmeade. “If it’s done with passion, you can’t say that it’s boring and uninteresting.”

Most people know Mr. Kilmeade as co-host of the Fox News morning show “Fox & Friends.” He’ll be the first to tell you he loves his job. But his passion is history. Mr. Kilmeade is the author of eight books, all related in some way to American history. His first two, written more than 15 years ago, are sports-related. His last six, however, discuss more serious historical matters.

Mr. Kilmeade has written about George Washington’s spy ring, Thomas Jefferson’s war against the Barbary pirates, Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans, Sam Houston and the Texas Revolution, the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, and, most recently, the relationship between Theodore Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington. Although the first four focused on American military history, the tune changes slightly in his last two offerings. He suggests that the change is more incidental than predetermined.

“I’m just trying to move through time, and I got to the Civil War,” he said. “It was really about [Lincoln and Douglass] and how they got through that rough time together. Their partnership was way too short, but very effective. Then we had Reconstruction, then the falling apart of Reconstruction, then the 20th century, and then in comes Jim Crow, and I thought how do I move through time and tell the story between two people.”

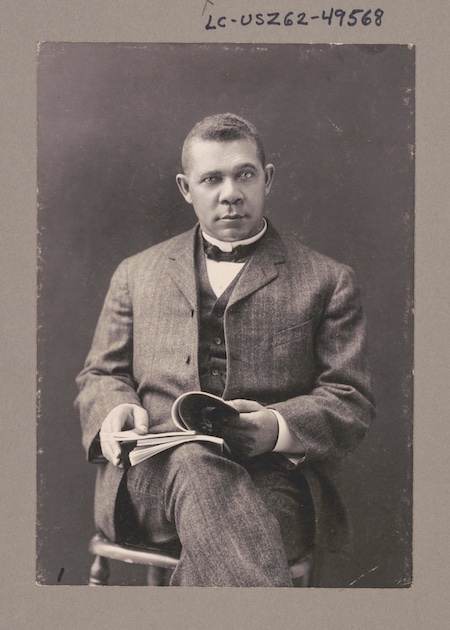

Mr. Kilmeade said he had read Washington’s autobiography “Up from Slavery” before he settled on writing about Lincoln and Douglass. The book captivated him, and then he learned that Theodore Roosevelt had been just as taken by Washington’s writing.

Roosevelt and Washington: Self-Made Men

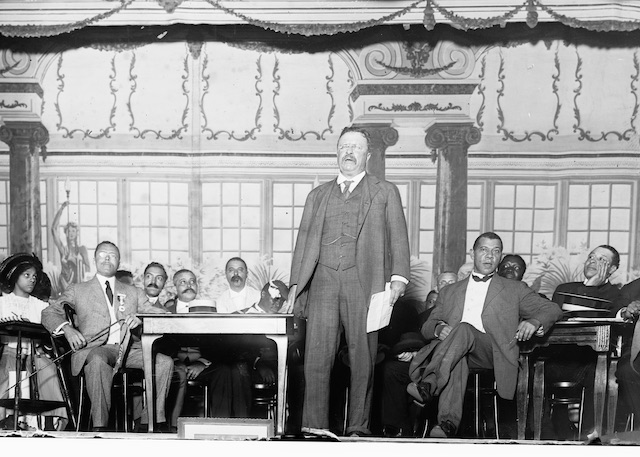

“After Teddy Roosevelt did what I did (that’s my only comparison with Teddy Roosevelt, I promise) and read ‘Up from Slavery,’ [he] gave it to his wife, who couldn’t put it down. And she said, ‘We have to meet this guy,’” Mr. Kilmeade said. “The first time they met was April 1, 1901. They immediately knew they could help each other.”

Roosevelt and Washington, despite growing up in vastly different environments, had something important in common, Mr. Kilmeade explained. They were both self-made men.

Washington, as his autobiography suggests, was born a slave nine years before the end of the Civil War. After emancipation, his family moved to West Virginia, where he worked in a salt furnace and a coal mine. Desiring an education, he traveled, mainly on foot, to Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) in 1872. He was provided a job as a janitor to pay his room and board, and a benefactor paid for his education. After graduating in 1875, he went back to West Virginia to teach for two years. He returned to university for eight months at Wayland Seminary in the nation’s capital. He joined the staff at Hampton, but he was soon selected to lead a new school in Alabama: the Tuskegee Normal School (now Tuskegee University), an institution to train African American teachers. Under his guidance, the school grew exponentially. Washington went on to write 40 books, became a prolific speaker, and assembled a network of some of the nation’s most powerful people, including Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Teddy Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was born to an uncertain fate. Plagued by illness, including asthma, the future president was not expected to live very long. His father advised him, “You have the mind but you have not the body. You must make your body.” Roosevelt began a lifelong undertaking of sporting challenges, including hunting, hiking, boxing, and exploration. Roosevelt, along with his speeches, wrote 45 books, and he became one of the most influential politicians in American history.

Keeping the Path

Seven months after their first meeting, Washington was invited to dine with Roosevelt and his family at the White House. It was the first time a black person had ever dined at the White House, and the only time for a long period afterward due to political and social backlash. This backlash came primarily from the Southern press and politicians.

“In their case, they changed their strategy, but they didn’t change their relationship,” Mr. Kilmeade said. “Roosevelt was totally shocked by it. But they kept their path together. They would have done more if they thought America was ready for it.”

Mr. Kilmeade explained that both Roosevelt and Washington continued to help each other’s causes. Whether it was Roosevelt assisting Washington’s pursuit for educational progress within the black community, or Washington assisting Roosevelt in obtaining the black vote for reelection, the two forged a bond that, as Mr. Kilmeade’s book suggests, cleared a path for racial equality.

The topic of Mr. Kilmeade’s two latest books is the idea of racial equality. He believes the topic is timely for a moment where “we seem to be more obsessed with race in this country, now more than ever.”

(This is a short preview of a story from the May Issue, Volume 4.)