Charles Carroll of Carrollton might well have been the Elon Musk of his day. The last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence was certainly an influencer. Carroll sponsored advances in agriculture, and, encouraged by his partnership with John, George, and Andrew Ellicott, Carroll promoted the use of crop rotation and pulverized limestone on his large Maryland estate. In 1828, he also laid the cornerstone for one of America’s first railroads, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O).

At the time, as connection to the West was a major concern for many in the young nation, Carroll had already helped found the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company (C&O Canal). That canal began in Washington, D.C., and followed the Potomac River west. Likewise, George Washington helped build the James River and Kanawha Canal, which was designed to connect the Ohio Valley with the coast by way of Richmond, Virginia.

Without such connections, trade would logically flow to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing the former British colonies altogether—but there were the mountains to reckon with. The Great Falls of the Potomac stood in the way for the C&O Canal as well. The James River and Kanawha Canal made its way through the Blue Ridge Mountains following the path cut by the James—but then there were the Alleghenies.

An incredibly complex system of locks, canals, and even tunnels would be necessary to connect the two watersheds. Each lock was an amazing bit of masonry and wood construction, allowing boats to rise and descend between levels of the canal. Remains can still be seen along the Maury River in Rockbridge County, Virginia, today.

The coming of the railroad opened up new avenues of westward commerce. No longer dependent on a regularly flowing system of waterways, and requiring less excavation, railroads could facilitate travel across the entire country. They needed no complex locks to cross the mountains, only a steady grade, and that required bridges and tunnels.

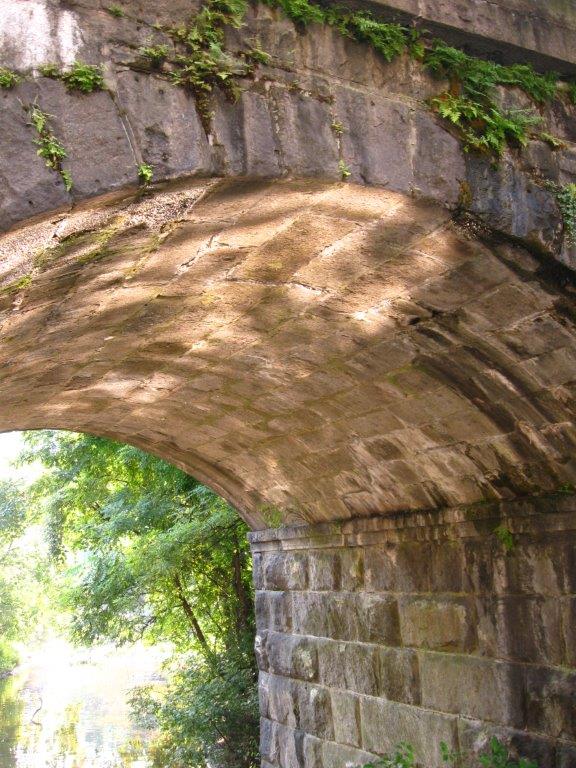

The B&O wound its way out of Baltimore along the Patapsco River on a gentle grade, while ample locally quarried granite allowed for the construction of some fine viaducts and other necessary structures.

A Roman arch was employed in America’s very first railroad bridge, the Carrollton Viaduct, named after Carroll’s estate. Initially the tracks had no ties; instead, straps of iron were laid on top of continuous granite pieces that ran along the length of the road, allowing a smooth path for the horses that pulled the first railway carriages.

The completion of the first 13 miles of track, to Ellicott’s Mills, created a popular excursion for the residents of Baltimore.

In the early days of the B&O, the motive power was provided by horses, but horsepower would soon become a standard instead of a literal fact. Although it lost its famous race with a horse-drawn carriage, Peter Cooper’s small locomotive “Tom Thumb,” with its upright boiler, would—together with steam engines in general—define the future of railroading.

In the interim, however, even wind power was considered. Evan Thomas of Baltimore constructed an experimental wicker railroad car with a sail, which he named the Aeolus. When there was enough wind blowing in the right direction to make it functional, it was operated on the tracks between Baltimore and Ellicott’s Mills.

The Russian Ambassador to the United States, Paul von Krüdener, came to observe the operation of the experimental car, and actually handled the sail on the trip. In return, the president of the B&O presented the ambassador with a model of the car. The occasion led to an exchange of American engineers who helped construct Russia’s rail system.

In England, nobility resisted the building of railroads. The Duke of Wellington said of civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Western Railway, from London to Bristol, “It will encourage the working classes to move about!”

America’s leaders, on the other hand, chartered railways with enthusiasm, knowing that westward movement would be essential to the building of the republic. The B&O pressed on to Wheeling, West Virginia (then Virginia), and the Ohio River. A line was built between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., for which Benjamin Henry Latrobe II, son of America’s first formally trained architect, designed the elegant Thomas Viaduct to carry trains across the Patapsco. A curved viaduct of Roman arches, it remains in use today.

Around 1853, Charles A. Dana published a beautiful lithograph of it in his book, “The United States Illustrated,” writing of it:

The “Pons Narniensis,” whose framer was the imperial Augustus; the arches of Trajan over the Danube, and the bridge of Alcantara across the Spanish Tagus, have long been famous in ancient history, whilst America, for the accommodation of no imperial cortege, but of the masses of the people, has rivalled them all in her numerous railroad viaducts, and especially in the Starucca Viaduct upon the Erie Railroad.

The one given in the engraving was of the first built in the country, although exceeded by the one above named in length, breadth, height, and the span of the arches, it is not surpassed for beauty of location and compactness of execution.

Claudius Crozet was born on Dec. 31, 1789, in Villefranche, France. He studied at the École Polytechnique and became an engineer in the French Army, serving under Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1816 he resigned his commission and came to the United States, where in 1858 he completed what was at its time one of the longest railway tunnels in the world. Measuring 4,237 feet, it was one of a series of tunnels that Crozet designed to carry the Virginia Central Railroad through the Blue Ridge Mountains and on into the Alleghenies. The Western Portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel is a magnificent stone arch; it’s a parabolic arch rather than a strictly Roman one, to allow for locomotive stacks and ventilation.

As late as 1874, the B&O was still building stone viaducts as it advanced a railway line through Virginia to Lexington, Kentucky. One particularly fine example may be seen by travelers on Interstate 81 as they drive through Augusta County in Virginia.

Bob Kirchman is an architectural illustrator who lives in Augusta County, Virginia, with his wife, Pam. He teaches studio art (with a good deal of art history thrown in) to students in the Augusta Christian Educators Homeschool Coop. Kirchman is an avid hiker and loves exploring the hidden wonders of the Blue Ridge Mountains.