As American as apple pie. It’s an expression commonly used to describe something that completely encapsulates the American character.

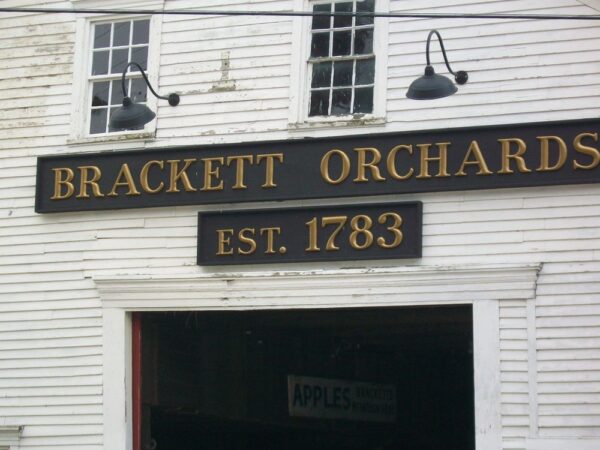

But surprisingly, the kinds of apples we commonly see in our markets and grocery stores are not actually indigenous to the United States. The crab apple is the only species in the genus Malus that is native to North America; it was English settlers who brought cultivated apple seeds with them. According to the University of Illinois, the first apple trees were planted by pilgrims in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Americans soon started grafting different cultivars, and today, there are roughly 2,500 varieties grown in the country.

Meanwhile, the earliest forms of pie were oblong—meant to transport food easily and preserve food for longer periods in the age before refrigeration. The crust was often inedible.

The first truly American apple pie recipe appeared in “American Cookery,” by Amelia Simmons, published in 1796. The cookbook is considered to be the first to use ingredients and cooking techniques distinct from the English tradition. True to American taste, the recipe called for cinnamon and mace—the outer covering of nutmeg—as spices.

Expressing Ourselves

Why did the apple pie become America’s signature dessert and a symbol of Americana? Ken Haedrich, author of several pie cookbooks, including the most recent “Pie Academy,” believes the versatility of the pie is a reflection of America’s love for self-expression.

“We’re all cowboys, you know. We like to do our own thing. And an apple pie is great for that. You can use virtually any type of apple that you want, any type of sweetening, any type of thickener, you can put a top crust or no crust, you can put a crumb topping,” explained Haedrich, who describes himself as a “pie apostle” and runs an online forum devoted to helping bakers with pie-related quandaries. “I think this is one of the things that has made apple pie the quintessential American pie—the fact that we can shape it into anything we want it to be.”

Pie is not only an expression of individual personality but also of America’s different regional attributes. In parts of New England where there is a lot of dairy production, a tradition emerged to place a slice of cheddar cheese on top of apple pie. “You start to get this confluence of regional ingredients with apples, and you’re going to find that in every part of the country. They will have their own sort of variations of apple pies based on what else grows there or the area is known for,” Haedrich explained.

Some in New England also use maple syrup as a sweetener, while in parts of the country with large Amish communities, such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and other parts of the Midwest, apple custard pies are common due to their dairy farming.

But there are other fruits of the harvest represented through pie. In the South, pecan pie is the ultimate fall dessert as the nuts are harvested during that season. In the Pacific Northwest, Rebecca Bloom, founder of the Piedaho Bakery based in Hailey, Idaho, throws in cranberries with local Jonathan and Jonagold apples and thyme for a fall treat. The pie company also uses flash-frozen berries from Washington in pies that are served throughout the fall and winter. Bloom loves the wild huckleberries that grow in Idaho, but she has yet to find a way to source them adequately to make pie—though she hopes “one day maybe we will find a treasure trove of them!”

And in Indiana, the Hoosier sugar cream pie—made simply of cream, sugar, flour, and spices—emerged during lean times when eggs and fresh ingredients were not available, explained Capri Cafaro, cookbook author and host of “Eat Your Heartland Out,” a podcast on Midwestern food traditions. “We’re dealing with ingredients that […] could be utilized […] with the resources available to people,” she said.

Also in the Midwest, other types of pie became popular due to the waves of immigrants who settled in the region and introduced their culinary traditions, explained Cafaro. In the Upper Peninsula region of Michigan, handheld pies called pasties reign supreme. They are typically savory and trace back to immigrants from Cornwall, England, who came for mining jobs during the mid-1800s.

But the custardy, delicious pumpkin pie did not emerge as a classic fall dish until Thanksgiving became a regional holiday in New England during the 1800s, Cafaro explained. Many abolitionists in New England featured pumpkin pie in their writings, and it became a symbol of the movement. After President Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863, pumpkin pie became a symbol of the fall bounty.

There is also the wholly American tradition of making recipes developed by major food corporations to promote their products. One year, Cafaro won the third-place ribbon at the Ashtabula County Fair in Ohio for her peaches and cream pie—which incorporated gelatin. The recipe came from one published by Jell-O. During the mid-20th century, with the rise of industrial food, brands popularized many classic desserts, such as the icebox cake, made with Nabisco chocolate wafers, Cafaro explained. “They oftentimes become heirloom recipes in their own weird way.”

Fall Memories

For Haedrich, who grew up in New Jersey with six siblings, pie-making was a treasured fall family tradition.

“Mom and Dad used to pile all of us in the station wagon. We had an old Woody, and we’d go up into the hills around Plainfield,” he recalled. “They’d buy bushels, baskets full of apples, and they’d come back and they would make their apple pies together.” Mom was in charge of the apple filling, while Dad was the crust maker. He believes these kinds of precious memories are “one of the things that strengthens our ties, our love of apple pie, and our love of pie, period.”

Julianna Butler, a baker in Vermont, similarly feels that pie gives off a “homey feel”—a comfort food that “reminds you of your grandmother.” In fall 2019, Butler won second place in an apple pie baking contest held by a local farmers market. The winning recipe incorporated her experience working at a pie bakery in her hometown in Virginia. Pie is Butler’s favorite dessert; in fact, for her upcoming fall wedding, instead of serving a wedding cake, she plans to give out mini pumpkin, pecan, and apple pies from the Virginia bakery.

Bloom, of Piedaho, said she recalls baking pies—especially her grandfather’s favorite, pumpkin pie—as a young child, and gifting them to him on birthdays. Her grandfather has passed away, but she still makes the same recipe—with a few of her own tweaks—to this day.

Haedrich said many of the people who email him with pie-related queries mention how much they enjoy the tactile experience of making pie. “You get your hands into it, you get to smell all the lovely ingredients.” For those who are new to pie-making, he recommends that they just practice—and not worry too much about how it looks. “I always tell people, don’t be afraid of strutting your ugly pies. Everybody makes a lot of ugly pies when they first start out,” he said.

He notes the most important thing is to enjoy the process. “Just immerse yourself in it totally. Just enjoy every aspect of it.”