Walt Disney’s 1948 animated short, “The Legend of Johnny Appleseed,” famously depicts its main character as a Pennsylvania farmer yearning to join the pioneers heading west to the frontier. All those settlers would need something to eat—and so Disney’s Johnny is determined to plant apple trees across the land in order to feed them.

The real Johnny Appleseed—a “small, wiry man, full of restless activity” named John Chapman, born in Massachusetts in 1774—was indeed a trained orchardist, and he really did show up in Ohio Territory with “a horse-load of apple seeds” to plant. It’s no myth, either, that John Chapman introduced apple trees to large swathes of frontier territory, from modern Pennsylvania and Ohio to Indiana, Illinois, and even Canadian Ontario.

Orchards for Cider

But Chapman’s apples weren’t meant for eating at all (they would have been far too sour, anyway). No—the apples of the real Johnny Appleseed were meant for making hard cider. As a not-so-subtle Smithsonian Magazine headline framed it in 2014, “The Real Johnny Appleseed Brought Apples—and Booze—to the American Frontier.” Journalist Michael Pollan agreed, explaining in a 2015 interview, “Really, what Johnny Appleseed was doing and the reason he was welcome in every cabin in Ohio and Indiana was he was bringing the gift of alcohol to the frontier. He was our American Dionysus.” Perhaps as early as the 1810s, however, Chapman was already being referred to as “Johnny Appleseed,” recognized as such “in every log-cabin from the Ohio River to the Northern lakes, and westward to the prairies of […] Indiana,” according to an 1871 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine piece. Unfortunately, along with apple trees Chapman also planted countless acres of dogfennel, which he considered as possessing medicinal qualities; dogfennel is now seen as a pernicious weed.

And the real Appleseed’s motivations were also far more complicated than those of the happy planter portrayed in the Disney musical. Far from acting the altruistic scatterer of apple seeds tossed hither and thither wherever he happened to roam, Chapman was probably a shrewd entrepreneur. The nurseries Chapman planted weren’t open to all, but rather fenced off, each tree meant for selling to settlers for six and a quarter cents. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, some land speculation companies required prospective colonists to plant fifty apple trees on their land; since it took the better part of a decade for these trees to bear fruit, such planting would serve to prove the colonists’ commitment to develop the land over many years. The real Appleseed saw in this a business opportunity. He would thus plant a nursery, enter into a business partnership with someone in the area to manage the sale of the trees to arriving settlers eager to quickly fulfill the companies’ requirements, and then move on to repeat the process elsewhere. Two or three years later, he might return to tend to the nursery.

Traversing the Frontier and In Touch With Indians

This was a business model that demanded he labor “on the farthest verge of white settlements,” and it wasn’t an easy line of work. Chapman essentially lived life as a nomad—and a barefoot one at that. One newspaper described him as “barefooted and almost naked,” and for a time he apparently wore a coffee sack, having cut out holes for his head and appendages. (There was, too, his signature hat: a tin vessel, with a visor-like peak in the front, that doubled as a pot for cooking.) The work itself could be hazardous. Once, while working in a tree, he fell and got his neck stuck between forking branches. If one of his helpers that day, a mere lad of eight years, hadn’t discovered him and run for help, the real Johnny Appleseed might have died in 1819. And as far away as they might have seemed from America’s economic centers, Chapman’s enterprises weren’t immune from the vicissitudes of the larger economy. When recession racked the United States in 1837, the price of his trees plummeted to just two cents apiece.

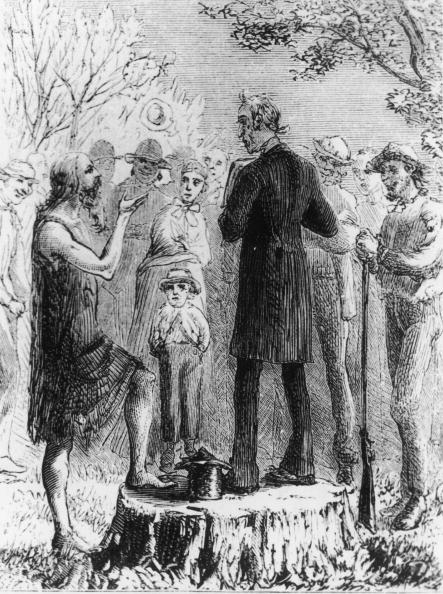

The frontier along which he worked, skirting American Indian country, could also be dangerous. But the natives, whom Chapman always admired and whose wilderness trails he often traversed, left the real Appleseed alone, considering him something of a medicine man; how else could one explain the privation and exposure which he so easily endured? Even during the War of 1812, when many natives along the frontier allied with Britain to devastate white frontier communities, Chapman never ceased his wanderings, and he was never harmed. One frontier settler, reporting his experience during this period, remembered with a “thrill” the peripatetic Chapman’s timely warning to his community: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, and he hath anointed me to blow the trumpet in the wilderness, and sound an alarm in the forest; for behold, the tribes of the heathen are round about your doors, and a devouring flame followed after them.” The real Appleseed’s warnings may have saved hundreds of lives.

Disney’s cartoon Johnny makes friends with a skunk and is beloved by all animals. In truth, the land he traversed teemed with potentially menacing wild animals, including wolves, rattlesnakes, wild hogs, and bears. One account of Chapman, however, does claim he had partially tamed a pet wolf, which followed him around everywhere he went, and his religious fervor (he followed Swedenborgianism) did eventually cultivate in him an almost Jain-like respect for all living creatures. By the time of his death, he had become a full-fledged vegetarian.

An Orator and a Gift-giver

As an itinerant orchardist-nurseryman, the real Appleseed, with his “long dark hair, a scanty beard that was never shaved, and keen black eyes,” was well-known up and down the frontier. This meant Chapman was often “passing through” the towns and settlements and American Indian villages of the region (in the words of one 19th-century newspaper, he “sauntered through town eating his dry rusk and cold meat”). Frequently, he would stop to entertain groups of children—apparently he was a master storyteller—or preach “on the mysteries of his religious faith” to any adult who might listen. To little girls he gifted bits of ribbon and calico; “Many a grandmother in Ohio and Indiana,” reported an article published a few decades after his death, “can remember the presents she received when a child from poor homeless Johnny Appleseed.” Once, after being gifted shoes for his bare feet by a particularly assertive settler, he was discovered a few days later again walking barefoot in the cold; the settler confronted him “with some degree of anger,” only to find out that Chapman had almost immediately re-gifted the shoes to a poor family, some of them barefoot, traveling west.

Days after strolling through the streets of Fort Wayne, Indiana, the real Appleseed died suddenly. The year was 1845, and John Chapman was around 70 years old. He was hailed in one obituary for “his eccentricity,” his “strange garb,” his material self-denial (apparently his faith had worn away at the material entrepreneurship of his youth), his “cheerfulness,” and his “shrewdness and penetration.” Johnny Appleseed was buried at Fort Wayne.

Within a quarter-century, the life of Johnny Appleseed was featured in the aforementioned Harper’s New Monthly Magazine piece, subtitled “A Pioneer Hero.” Even then, it was admitted that, as the frontier disappeared, “the pioneer character is rapidly becoming mythical.” The story of the nomadic nurseryman “whose whole [life] was devoted to the work of planting apple seeds in remote places” had begun to take on a life of its own—a myth which, by the mid-20th-century, had become musical Disney legend.

Dr. W. Kesler Jackson is a university professor of history. Known on YouTube as “The Nomadic Professor,” he offers online history courses featuring his signature on-location videos, filmed the world over, at NomadicProfessor.com