“Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives,” wrote President James Madison.

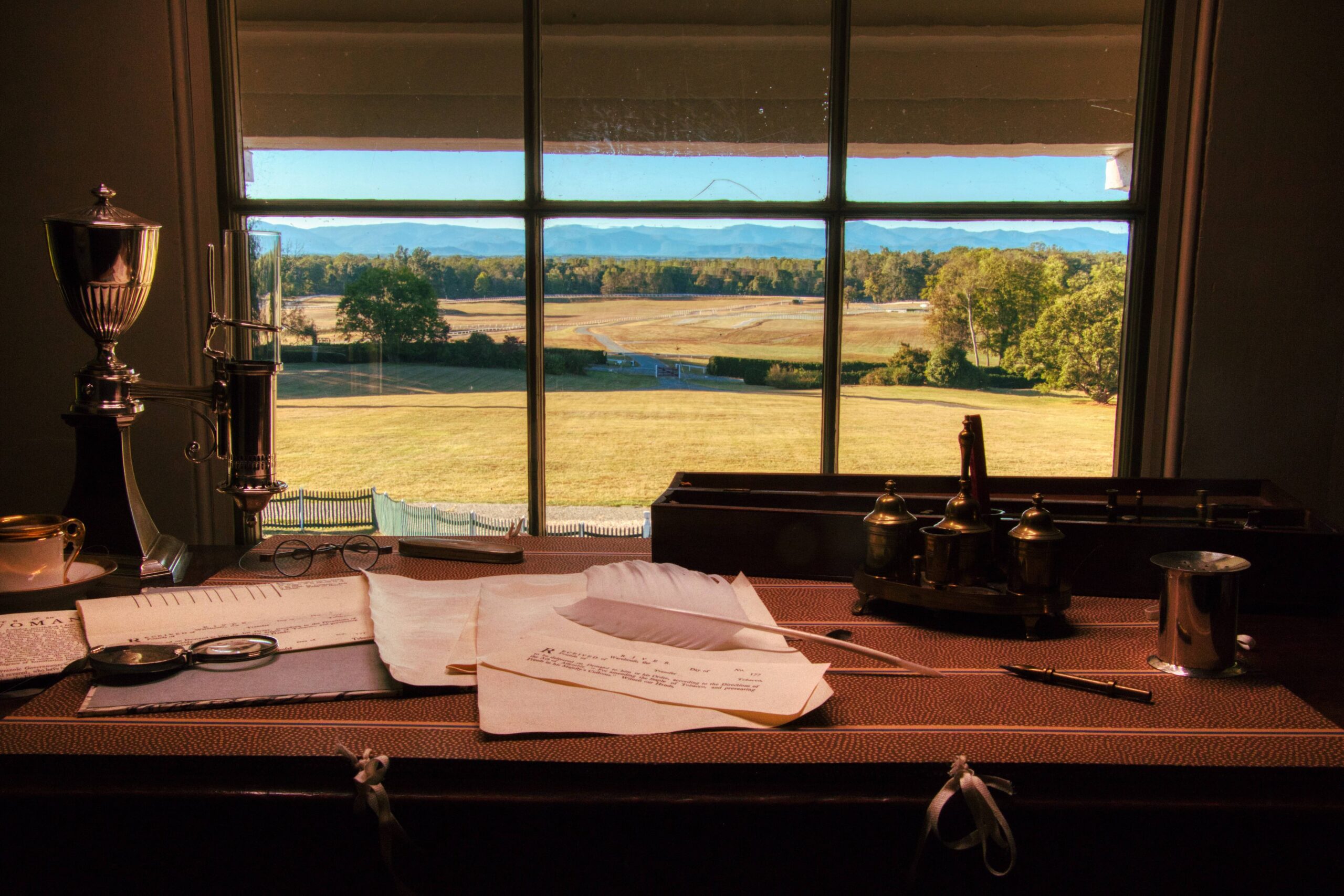

For six months, the “Father of the Constitution” sequestered himself in his upstairs study in the family’s Virginia home, Montpelier. There, he engaged in an intensive study of civilizations—both ancient and modern—in his quest for wisdom in shaping the Constitution of a young republic. Here, he synopsized his ideas into principles he felt essential for a representative democracy: what would be known as the “Virginia Plan,” which would become the basis for creating our Constitution.

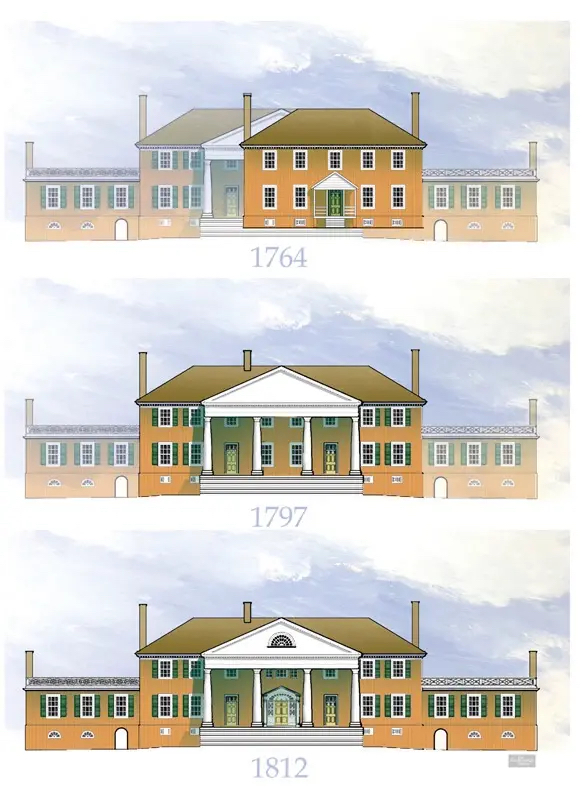

James Madison would always remember the day, as a youth of 14, when his family moved into the fine brick Georgian house. In fact, he helped carry in the furniture. His father, James Madison Sr., built the symmetrical house in Flemish bond (patterned brick) in the 1760s. It had a center hall and four rooms on the first floor and five rooms on the second. Crowning the house was a low hipped shingle roof with chimneys on both ends. James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” and fourth president, would consider Montpelier his home for the duration of his life.

Returning from Philadelphia, Madison brought his wife Dolley to his family’s Montpelier home in 1797. Seventeen years her senior, James Madison had married the recently widowed Dolley and adopted her son, John Payne Todd, three years prior. At Montpelier, the Madisons added a 30-foot addition to the house, creating a very fine multigenerational duplex, with separate living quarters for each generation. The older and younger Madisons would visit each other by way of the grand Tuscan portico that was added to the house at the time. It covered the two distinct entrance doors to each family’s part of the dwelling. There was no interior passage between them.

A careful examination of the facade reveals the place where the addition was joined to the original house, tying in the new brick to the original corner. Madison’s mother Nellie continued to live in the house following the death of James Sr. in 1801.

The younger James Madison had served in Congress, and he formerly “retired” from public service when he and Dolley moved to Montpelier. In 1801, Madison’s good friend Thomas Jefferson appointed him secretary of state. He served in that capacity until 1809, when he was elected president. During the next eight years, he and Dolley would serve as president and first lady, living in the President’s House until it was burned by the British in August 1814. After restoration, when the charred sandstone exterior was painted, the presidential mansion became the “White House.”

In 1809, Madison took some of his $25,000-a-year salary as president and began expanding Montpelier. He added one-story wings on either end of the house. On the south side, he created an apartment for his mother. On the north side, he built a library for his 4,000-volume collection. Thomas Jefferson designed a new grand entry door at the center of the mansion, which led into the Drawing Room, where the former president greeted visitors. Comparable to the hall of Jefferson’s Monticello, Madison’s Drawing Room became a showcase for his interests and ideals. It was designed to make a powerful impression.

According to historian Michael Quinn, Madison’s Drawing Room was intended to be a history lesson: “For Madison, the history of humanity was really his laboratory—and he had studied past attempts at self-government—so he knew that what America was today was founded on the past.” Prominently hung on the wall is a large painting featuring a Pan figure and a nymph, painted by Gerrit Van Honthorst around 1630. This 17th-century Dutch painting became a reference to the Greek and Roman world and the beginning of democracy. Next to it is a large painting of the “Supper at Emmaus,” a reference to the time when Biblical ideals informed the affairs of men.

According to Quinn, the final epoch of America’s foundation is represented by the series of presidential portraits arranged in a group. Washington’s portrait is alone at the top. Below are portraits of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe: the first president above the second, third, and fifth presidents. Quinn attributes Madison’s omission of his portrait in sequence, between Jefferson and Monroe, to two factors. First, Madison was an incredibly modest man, and second, where his portrait is placed in the room is next to that of his beloved Dolley. This, Quinn stated, shows you what was truly important to the man.

There are busts of many of the nation’s Founding Fathers in the Drawing Room—all friends of the Madisons—including George Washington, John Adams, James Monroe, and Benjamin Franklin. They entertained an endless stream of visitors in the years following the Madison presidency. The Marquis de Lafayette was a guest, as well as Andrew Jackson. If you came as a friend, or with a letter of introduction, you would be welcomed to come further into the family home. If you simply came to the house unannounced, you might only come into the drawing room, which served as a sort of early American visitor’s center.

If you were an invited guest to Montpelier, however, you might dine with the Madisons in their elegant Dining Room. The walls are covered in wallpaper known as “Virchaux Drapery,” which is of French design and creates the effect of being in a pavilion. This stylized drapery pattern was designed by the architect Joseph Ramée in partnership with Henry Virchaux, a French émigré printer working in Philadelphia between 1814 and 1816.

James Madison would not sit at the head of the table, as was culturally expected. He preferred to sit along the side. The head of the table would be occupied by Dolley, who directed and coordinated the meals. This arrangement was startling at first to visitors, but soon they found it quite agreeable. James and Dolley gracefully shared the tasks of entertaining: He was more often involved in the weighty affairs of state being discussed, while she enjoyed the art of hospitality.

Beyond the Dining Room is the wing containing Madison’s great library. It was built while he was away, serving as president, but clearly with a future purpose in mind. He had regular correspondence with his builder, James Dinsmore, who also worked for Thomas Jefferson. Mr. Dinsmore weighed in on the design of the library. A letter from Dinsmore reads:

I intended before you went from here to mention to you whether you would not think it advisable to put two windows in the end of the library room? But it escaped My Memory; I have been Reflecting on it Since and believe it will as without them the wall will have a very Dead appearance, and there will be no direct View towards the temple Should you ever build one. My reason for omitting them in the Drawing was that the Space might be occupyd (sic) for Book Shelves but I believe there will be sufficiency of room without as the piers between the windows will be large and the whole of the other end except the breadth of the door may be occupyd (sic) for that purpose.

The windows that Dinsmore suggested were put in, and the round classical temple was built. The library was planned as a space that was large enough for Madison to pursue his last great work: compiling, annotating, and expanding further upon the notes he had taken of the Constitutional Convention (May to September 1787) in order to complete a thorough record of the founding of America. The urgency he felt to perform this work was born in the months of research he had done prior to the convention. In the late 1780s, he carried out a great deal of research to study every historical attempt of mankind to form a democracy, confederation, or any method of representative government.

Madison found little documentation to guide him and numerous accounts of failure. He set out to produce a guide that exemplified the decision and debates of the American founders. During his final years, he wrote a thousand pages that were later compiled into “The Papers of James Madison,” providing a record for future men who may also be striving for liberty. Even in his 80s, visitors report that his mind was bright as he discussed these ideals. He died at the age of 85, on June 28, 1836—the oldest surviving delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Madison was always fearful that America’s own experiment in self governance might fail. After his death, a document he had written, “James Madison, Advice to My Country, December, 1830” was found among his papers. In it he wrote, with clear allusion to both classical and Biblical wisdom:

As this advice, if it ever see the light will not do it till I am no more, it may be considered as issuing from the tomb where truth alone can be respected, and the happiness of man alone consulted. … The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened; and the disguised one, as the Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise.

From Sept. Issue, Volume IV