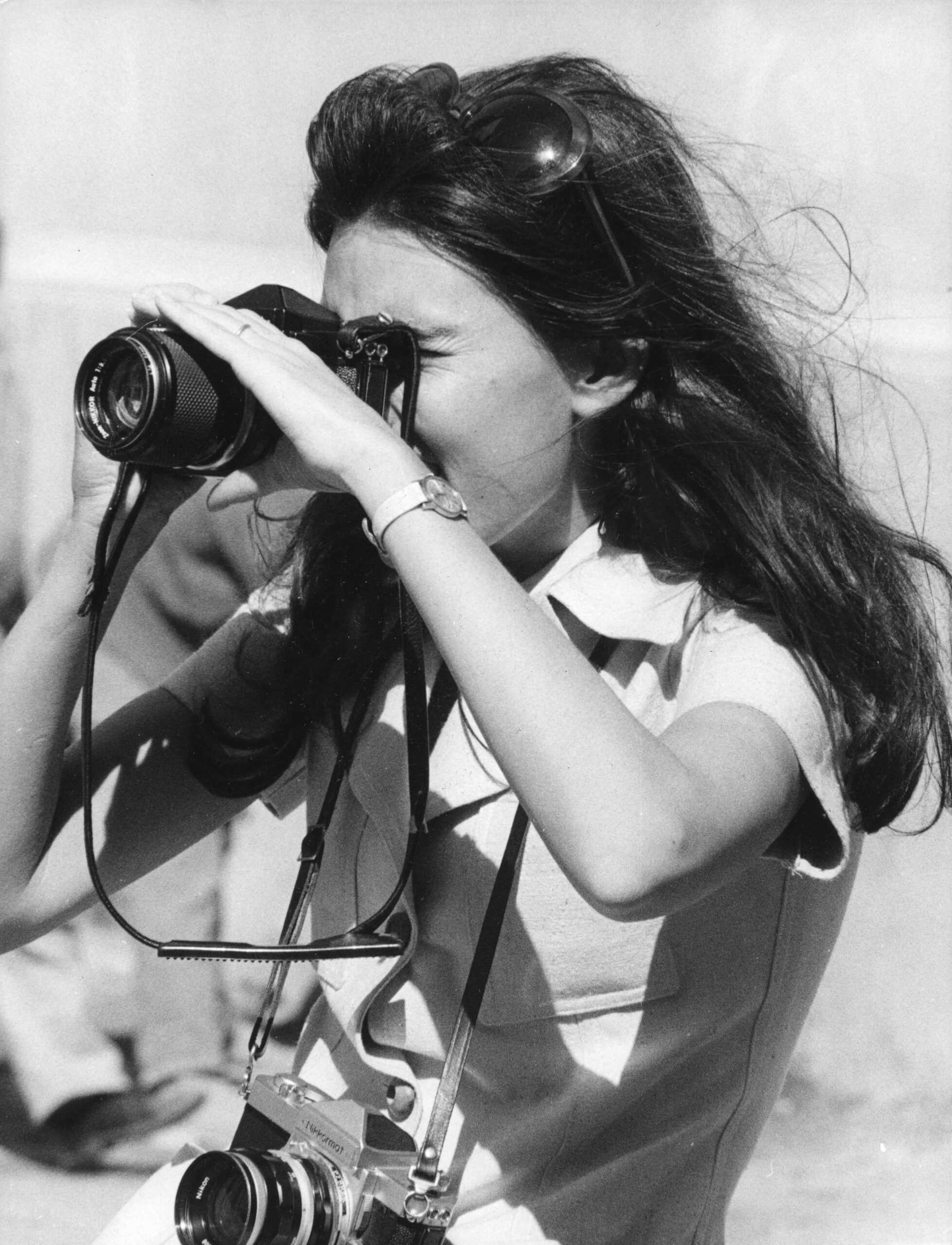

At her home in Queens, New York, Lidia Bastianich cooks with a view of the water. Opposite her sprawling kitchen and dining table, wall-to-wall windows look out over her garden to the idyllic Little Neck Bay, where sailboats bob serenely under blue skies.

Here is where the Italian refugee turned James Beard and Emmy Award-winning chef, restaurateur, TV personality, and author raised her children and her grandchildren; where she taught Julia Child how to make risotto; where she filmed the PBS shows that introduced millions of Americans to traditional Italian home cooking, inviting them around her table with her signature phrase: “Tutti a tavola a mangiare!” “Everyone to the table to eat!”

“I feel very American, and I feel very Italian here,” Ms. Bastianich told American Essence on a recent visit. There’s the proximity to the water, what drew her to buy the house in the first place 38 years ago—“since I came from the Adriatic, my dream was always water,” she said—and the garden lined with Italian fig and lemon trees, rosemary and wild fennel, grape trellises, and potted tomatoes—all echoes of the Mediterranean. “And at the same time,” she said, “I see the Empire State Building from my house.”

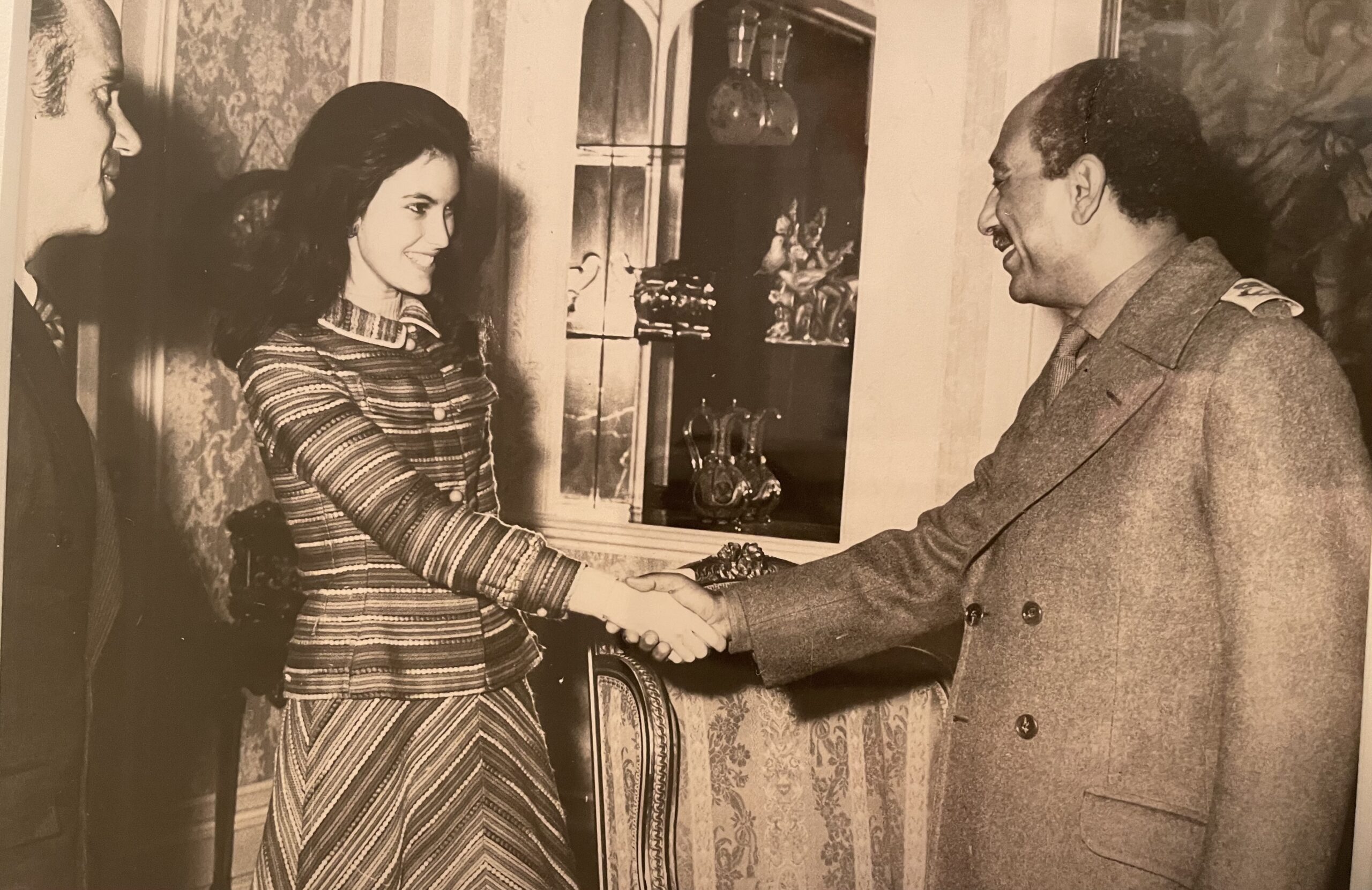

It’s a dual identity that she’s embraced from a young age. When she was 10, she and her family fled their home in communist-occupied Istria, a peninsula in northeastern Italy handed over to Yugoslavia in the aftermath of World War II. They waited two years in a refugee camp in Trieste, Italy, before finding freedom in America in 1958.

Since then, Ms. Bastianich has built her own version of the American Dream: a veritable culinary empire dedicated to sharing her cultural heritage with her new home. It has spanned several restaurants with her former husband, Felice, and now her children, Joe and Tanya; 25 years on air with more than a dozen companion cookbooks; a partnership in opening Eataly, an Italian food emporium, in New York and locations across the United States; and her own lines of pastas, sauces, and cookware.

She’s also made it her mission to champion the place that took her in and gave her the opportunity to succeed: “There’s no better country in the whole world,” she said. For an ongoing series of annual, hour-long specials, “Lidia Celebrates America,” she travels to meet, cook with, and share the stories of inspiring people across the country.

And at 76, Ms. Bastianich has hardly slowed down. Her latest cookbook, “Lidia’s From Our Family Table to Yours,” was released in September. The 11th season of her PBS show “Lidia’s Kitchen” premiered in October, and a special, “25 Years With Lidia: A Culinary Jubilee,” will premiere nationally on December 18 at 8 p.m. EST. Squeezing in our interview on a brief day home between travels—next, to Canada, for her book tour—she talks at the confident, no-nonsense clip of a matriarch and businesswoman who knows how to get things done, and fast.

What keeps her going? “I love what I do,” she said matter-of-factly. And indeed, she softens, both tone and expression taking on a grandmotherly warmth, when she speaks about her passions: food, family, and how the two have always been intertwined in her work and life. She spoke with American Essence about her immigrant journey, her sense of responsibility to her adopted home, and the extraordinary power of sharing a meal.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

American Essence: What are your strongest food memories associated with the different places in your life’s journey—from your birthplace of Pola, Istria [now Pula, Croatia], to the refugee camp in Trieste, and finally, to America?

Lidia Bastianich: I have to go back to when I was born: 1947, after the war. The Paris Treaty was in the same month, February, and the border came down: Trieste was given to Italy, and Istria and Dalmatia were given to the newly formed communist Yugoslavia.

We grew up in a country of radical change. Once the communists came, you could not speak Italian, they changed our name, we couldn’t go to church. My mother was a schoolteacher; my father was a mechanic, and he had two trucks. They took the trucks and deemed him a capitalist; they put him in jail for it. So life wasn’t that easy. Even food was scarce. My grandmother, who was in a little town, Busoler, outside of Pola, she raised food and animals to feed the whole family, so my mother took my brother and me out of the city and put us with Grandma. And I think that’s where my first basic food connections happened.

With my grandmother, we had chickens, we had ducks, we had geese, we had rabbits, we had goats, we had pigs, we had pigeons. Now and then it was a chicken that went into the pot, then it was a rabbit, then it was a pigeon. I would be feeding these animals. In the springtime, the rabbits loved clover, so I would go and harvest clover in the woods. We would milk the goats, make ricotta. We had two pigs every year, and slaughter was in November, so you had to feed them to get them nice and fat. After the slaughter, we made the sausages, the prosciutto, the bacon.

The garden was the extension of the house—we had the immediate vegetable garden, and then we had a little wheat field. We had olive trees. I was involved in harvesting the olives in November when the olive oil was made; I remember I would dip the bread in there and taste it. The wheat didn’t get all milled at once; Grandma kept the wheat kernels in a cantina, and she would go to the mill every month or two. We would brine the vegetables and the fruits for the winter; we’d pickle cabbage.

Everything had a season: the wild asparagus in spring, the nettles, and then, in the fall, the mushrooms and the squash. I helped my grandmother work the land, so I was aware when things would blossom. I was in tune. The small baby peas, Grandma let them grow because she would get more when it’s a mature pea, but as I would go and collect them, I ate them. I used to chew on the pods; they’re sweet, too. The figs, in August when they were plentiful, we would dry them in the sun so we would have them in the winter. I was involved in all of this—and not because she wanted to teach me, but because I was there as a little helper, that’s just the way it was. My grandmother would say, “Go get some rosemary,” and I would run to the rosemary bush, or to the bay leaves. I grew up with all of that. I knew all the smells, and that stayed with me. When you’re in your formative years, that stays with you.

But the real recall moment for me came in 1956. I was 10 years old. When the border went down in Trieste, some of my family was left on the Italian side. Supposedly, my aunt [in Trieste] wasn’t feeling well, so my mother and my brother and I went to visit her. They wouldn’t let the whole family go; they held someone as hostage because they knew we wouldn’t come back [otherwise]. The three of us went. The aunt was fine. But two weeks later, at night, my father appeared: He’d escaped the border. Then I realized that I’m not going to go back to see my grandmother. That’s when I really felt that need: I wanted to be connected, and food and smell built that connection. I think that my love and passion for food, my connection with food, goes back to those memories of wanting to be connected with Grandma, who I didn’t know when I was going to see. So I would cook things that I remembered with my aunt, the flavors that my grandmother was cooking.

We didn’t have Italian papers because we were under communism, so my parents went to the police and asked for asylum. For two years, we were in a political refugee camp, awaiting where to go. I remember in camp, we had a little cubby hole, and we had beds on top of each other.

I would recall all the beautiful times I had with Grandma that I maybe couldn’t have anymore, and I think that’s why it’s so embedded; it’s so vivid even to this day. People say, “Gee, Lidia, you remember the details.” I do, because I recalled them so many times in those years. Even when I came to the United States, the excitement of being free and having your own home and the greatness of America—still, your roots are your roots.

AE: After you came to America, how did your experiences with food change?

Ms. Bastianich: [I remember] the excitement of American food. The Twinkies. Hostess. Jell-O. I’d never had a grapefruit. All these foods—they’re delicious! When we settled, my mother worked late, so she would leave me to do the dinner, and every night [I made] a cake. Those pre-mixes—I couldn’t get enough of them! I was watching the Ed Sullivan show, Elvis Presley, all of that. I wanted every single thing that was American; I wanted to become American as soon as I could. We didn’t speak English when we came, but my brother and I, within a year, we began to.

Then, of course, as I went on into my profession, I realized that maybe the connection to real food was the way it’s supposed to be. Big industry took a lot of liberties with creating our foods. What is amazing is that from my formative years to my professional years, I reverted back to what we did [in Busoler] and how important it was. It’s like 360 degrees, now and then. I think us chefs, we have a big role to play, and I think that’s why with my show and my books, I feel that I share the authenticity that I grew up with.

AE: In addition to your regular show, your series of specials celebrates America. How did the idea for these specials come about?

Ms. Bastianich: I wanted to share my gratitude and my curiosity in understanding America better from my point of view, having been a young immigrant, having been given the opportunity to come to America. America has been sort of knocked down. You’ve got to rally against this. So it’s my way, as an immigrant, of telling Americans, “Listen, there’s no better country, I can tell you that.”

Food opens all the doors. Food is a common denominator, no matter what culture you are: You sit at the table, you begin to cook together, and you become friends. And when you talk with food, the conversation is mellow. So I use food to sort of penetrate messages.

I did two veteran specials, because I don’t think people realize how our soldiers are out there giving their lives to protect our freedom. I visited with veterans, and we cooked together. I did one thanking all the first responders.

The last one was on immigrants, because I think immigrants are maligned now, but we’re all immigrants. I went around to different ethnic communities: I went to South Carolina, to a Ukrainian son and mother; then I went to Houston, to the Afghan community. My Vietnamese friend Christine Ha, she’s a blind chef, she was born here but her parents were from Vietnam. She says, “At home, I was Vietnamese, but outside, I was American.” As an immigrant, you’re lucky enough to have these cultures on top of being an American.

America is made out of different ethnicities: It’s like a quilt, and it’s beautiful, and it’s strong. And what’s amazing about this is that within this context, we can all be who we are culturally: We can practice our religion, speak our language, sing our songs, have our social gatherings.

But what immigrants need to also understand is that they’re given this great opportunity, and you need to take opportunities that you think fit, and you need to work hard at that. You need to make it happen, and really be responsible, and at the end, you need to give back to this country. [In the special] there’s this family from Bhutan, where they were persecuted, so they were in Nepal as immigrants for over 18 years. When they came here, he [Bhuwan Pyakurel] was still a young man. He ultimately became an assemblyman for his community [in Reynoldsburg, Ohio].

You have to become part of society, and you have to appreciate it. Certainly, I feel that way: As an immigrant, I feel very grateful for the opportunities that my family was given. In turn, I had my children here, my grandchildren, and I never stopped telling them that. I took them back to the refugee camp and the trip that I took—and not just I, but many other people, whether from Europe, from Africa, from Asia, to escape dire conditions. What parents do to better the lives of their children! Kids need to know, immigrants need to understand the gifts that they’ve been given and make the most of it.

AE: You’ve written a new cookbook of your own family’s favorite recipes, in part a tribute to your late mother, Erminia Motika, known to your family and fans as “Grandma.” Can you talk about who she was to you?

Ms. Bastianich: My mother passed away two years ago at 100. We lived together; she lived upstairs, I lived down. She was matriarch. She helped me raise my children, and in turn, we helped to raise my children’s children. They all remember her vividly—we all do.

When you think about this woman, 30-some years old with two young children, going into the world not speaking the language, not having anybody in the States, not having money—how much strength it took for her and my father to do that so that our lives could be better. She was a strong woman who appreciated, loved America. She realized what America could be to her family. She was the pole that held everything together.

Nothing was done without Grandma, so she automatically came right into the shows and articles; the viewers loved her. People said, “She’s my grandma, she’s the grandma I lost.” She became kind of everyone’s grandma. We still give her a tribute, I want her in the show: At the end, we have little clips where we sing together, and people love that.

AE: What upcoming projects are you most excited about?

Ms. Bastianich: The continuation of my show. I pulled back a little bit from the restaurants—my kids are running the restaurants, and I have new projects going on. I have more freedom. We’re just finishing my 25-year special, and then I’m working on another book. The next one is all about pasta: fresh pasta, dried pasta, making it, cooking it. I’m excited about it.

AE: What is the most important life advice you want to pass on to your grandchildren, and other young people?

Ms. Bastianich: Eating together at the table is an extraordinary place to be. Because when you’re eating, your defenses are down, you can talk. As human beings, we’re smart, we’re defensive, we are protective. But when we’re eating, that’s one of the few things that we take into our bodies—food—and our defenses are going to be down to take it in. Especially when parents want to talk to children about life, the table is the ideal place because children are open, are receptive, and they’re taking in what you’re saying, too. You don’t need to make a festive meal. A nice plate of pasta, it’ll get people to the table.

Lidia’s Loves

Three ingredients you’d bring to a deserted island: Olive oil, pasta, and garlic

One thing you do every morning: Make a cappuccino

Someone you’d most like to cook with: My maternal grandmother

Favorite hobby when you’re not cooking: Sailing

Favorite way to relax: Listening to classical music

Best advice you’ve ever received: Be humble, listen well, and take a pause before responding

Thanksgiving at Lidia’s

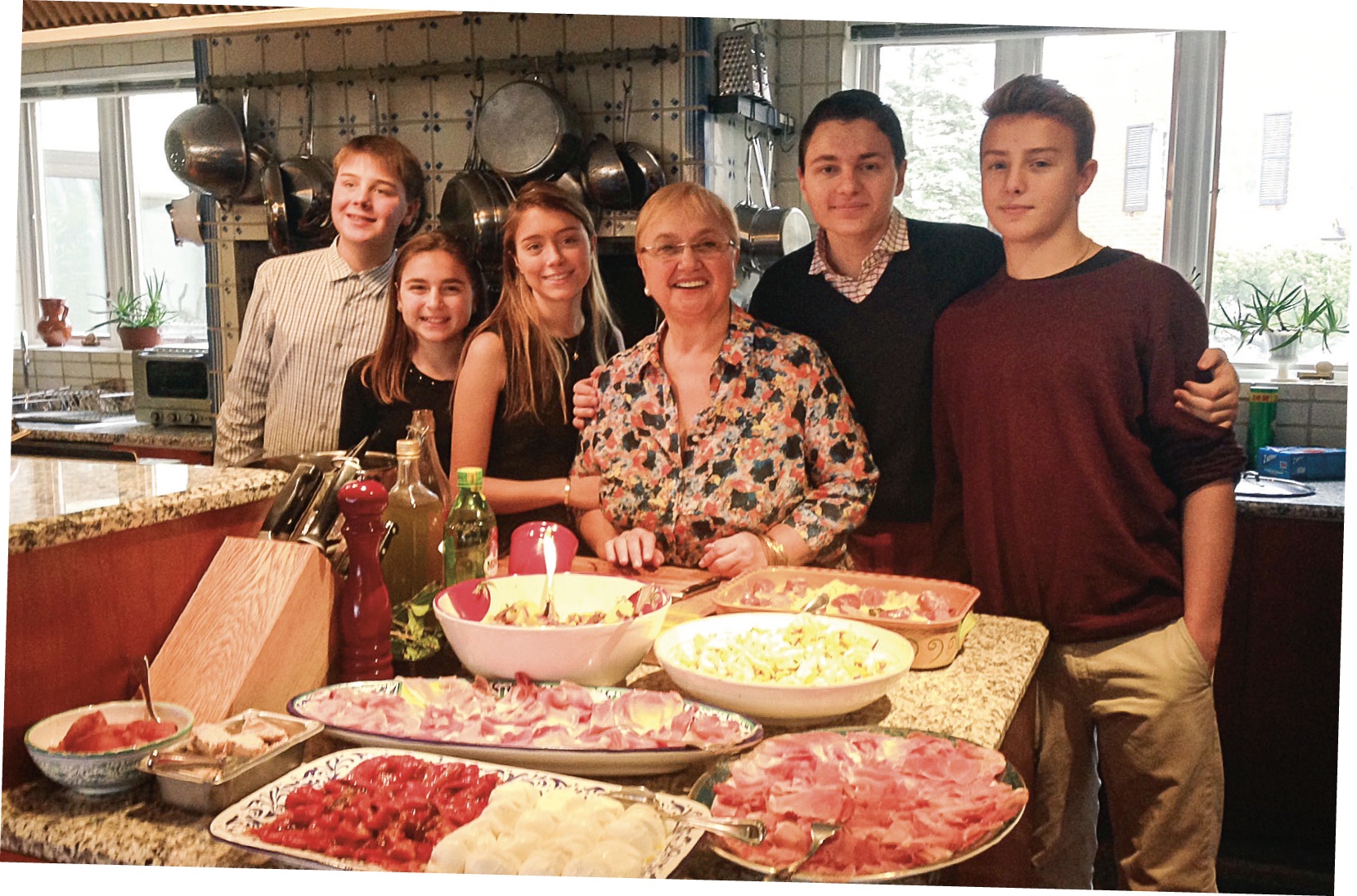

For Lidia Bastianich, Thanksgiving is a holiday about “celebrating the country that took us in,” she said. Her family gathers in her New York home, joined by a few regulars who have no family of their own and have been part of the Bastianich holiday celebrations for years.

“We fill the whole house,” Ms. Bastianich said—and of course, she does the cooking. “For me, cooking for 20, 30 people? Not a big deal.”

The meal starts with a “never-ending” antipasto buffet: “We like fish, so it’s octopus, it’s mussels, it’s calamari, it’s baccala. … And then, of course, all the cold cuts—mortadella, prosciutto, gorgonzola, parmigiana. Then all the cured olives and roasted peppers, lots of roasted vegetables, salads, a lot of greens, cured anchovies, mozzarella.”

Then comes a soup or pasta course (“We make it a little Italian,” Ms. Bastianich said) followed by the turkey with all the fixings, served family-style at the dining table. Dessert is again buffet-style: The kids usually bring pumpkin pie and bread pudding, while Ms. Bastianich makes an apple strudel or cheesecake.

Tips for Home Cooks

Use your oven space wisely: The turkey gets priority, with some sides delegated to cook on the stovetop instead. “Us Italians, we do a lot of garlic-and-oil vegetables in the pan.”

Glaze your bird: Ms. Bastianich simmers balsamic vinegar with bay leaves, rosemary, a couple of garlic cloves, and honey in a pan on the stovetop until reduced by about half, then strains the resulting syrup and brushes it on the turkey in the last half hour of roasting. “That gives it a nice Italian touch and some sweetness.”

RECIPE: PORK CHOPS WITH MUSHROOMS AND PICKLED PEPERONCINI

From Nov. Issue, Volume III