Tiffany is a name that’s synonymous with the enchanting and sublimely beautiful glassware of the Art Nouveau movement in the United States.

With a career spanning from the 1870s through the 1920s, Louis Comfort Tiffany embraced virtually every artistic medium: leaded-glass windows, mosaics, lamps, glass, pottery, jewelry, and furniture. Of all Tiffany’s artistic accomplishments, it was his innovation in leaded glass that brought him the most recognition. Tiffany was among the first U.S. designers to be acclaimed abroad. His techniques in glass and the union of his craft with American arts set him apart as the most innovative designer at the turn of the century.

“I have always striven to fix beauty in wood or stone or glass or pottery, in oil or watercolor, by using whatever seemed fittest for the expression of beauty.”

—Louis C. Tiffany

Louis C. Tiffany was the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder of the successful and influential silver and jewelry firm Tiffany & Co. In lieu of working for his father’s business, Louis C. Tiffany chose to pursue his own artistic interests. The young Tiffany began his career as a painter, working and studying under the tutelage of American landscape artist George Inness. Inness is reputed to have remarked of Tiffany: “The more I teach him the less he knows, and the older he grows the farther he is from what he ought to be.”

Tiffany’s fervor for the arts led him to France, where he studied with Léon Belly in Paris. It was Belly’s exhibition of Islamic genre scenes and landscapes that initially opened Tiffany’s eyes to a bright world of patterns and colors—which became Tiffany’s signature trademark for his leaded glass. In spring 1869, he met artist Samuel Colman, cofounder and first president of the American Watercolor Society. Colman taught Tiffany the value of watercolors for sketching, and together they traveled to Spain and North Africa in search of exotic subjects. Tiffany spent his time in North Africa collecting photographs, glassware, and objects that helped further formulate new ideas and theories about color.

“When first I had a chance to travel in the Near East and to paint where the people and the buildings are also clad in beautiful hues, the pre-eminence of color in the world was brought forcibly to my attention. I returned to New York wondering why we made so little use of our eyes, why we refrained so obstinately from taking advantage of color in our architecture and our clothing when Nature indicates its mastership.”

—Louis C. Tiffany

The Gilded Age

The term “Gilded Age” was coined by writers Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner to represent the era of American opulence. The reconstruction of the United States following the Civil War was a time of unprecedented economic development. Manufacturing production boomed and railways grew across the United States, attracting millions of migrants to the nation. The economic wealth financed the growth of the luxury goods market, and wealthy art patrons sought extravagance as a way of displaying status. The Gilded Age set the stage for the rise of the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States.

The Arts and Crafts movement had already gained popularity in Victorian England during the second half of the 19th century. The return to traditional styles of artisan design was a direct revolt against the Industrial Revolution and what was felt to be the “soulless industrialization of craft.” British artist, designer, and philosopher William Morris led the movement and believed production by machinery to be “altogether evil.” He also advocated for the union of all arts within the field of interior design, emphasizing nature and simplicity of form. The theme of nature remained a powerful iconography throughout the Arts and Crafts movement—especially in the works of Tiffany and in the aesthetics of Art Nouveau.

In 1876, Tiffany was first exposed to the lure of the movement when he exhibited his paintings at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. It was then that he became attracted to the decorative arts and began to think about moving his artistry into the field of design, remarking to a fellow exhibitor: “I believe there is more in it than painting pictures.”

Tiffany embarked on a design career in 1879, opening the interior design firm Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated American Artists, together with Candace Wheeler, Lockwood de Forest, and Colman. In the company’s four short years of existence, it fulfilled numerous interior design commissions, including contracts to design home interiors for wealthy clients such as writer Mark Twain, actor and inventor James Steele MacKaye, and President Chester Alan Arthur.

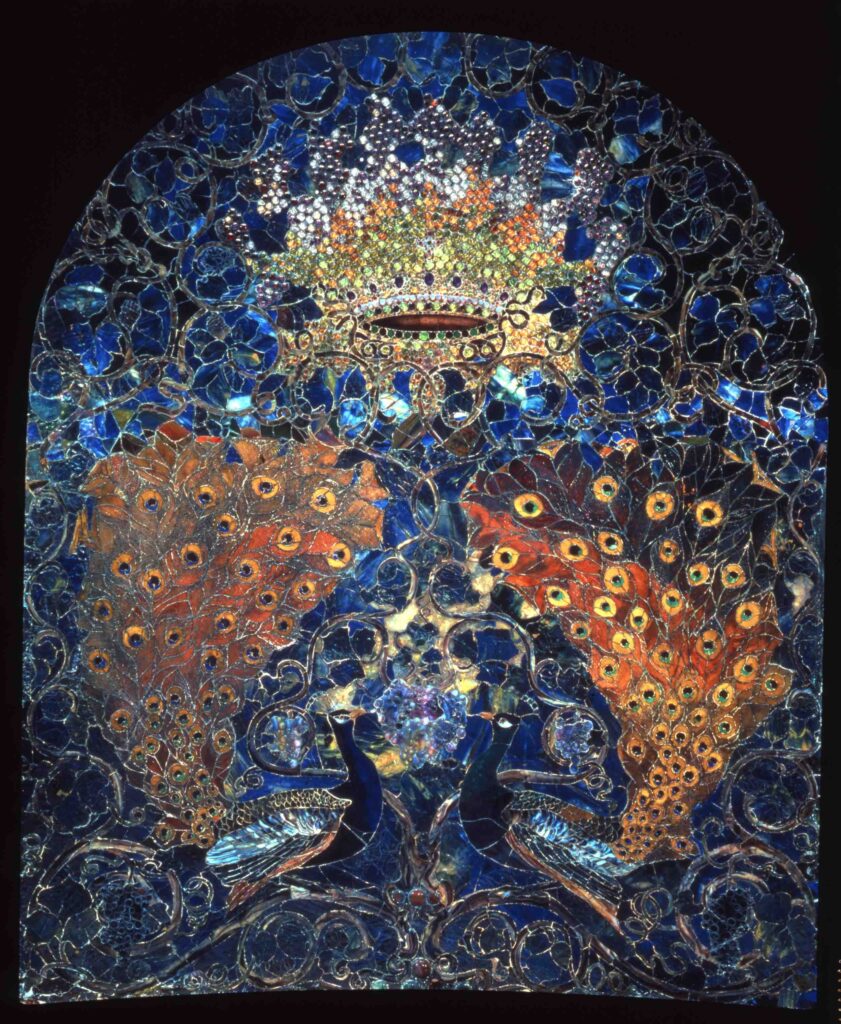

The Rise of Tiffany Glass

In the early 1870s, Tiffany’s passion for glass blossomed and he began experimenting with different techniques and materials. Between 1880 and 1881, Tiffany filed three patents for his glass-making process. One patent was for the creation of iridescent glass tesserae (small square tiles used in mosaics). Traditional mosaics were made with squares of uniform color. Tiffany’s innovations in glass-making technique, however, allowed for the creation of mosaics with shimmering tiles that were both iridescent and luminous.

Another patented technique utilized metallic oxides to create iridescent window glass. While Tiffany wasn’t the first to invent iridescent glass, he’s the most recognized for popularizing it on the market. Prior to 1880, iridescence in modern glassmaking was used in Venice, Italy, and earlier by Scottish physicist Sir David Brewster, who experimented with iridescent patina.

The third patent involved inducing opalescence by layering stained-glass panels. Tiffany and his early rival John La Farge, another prominent glassmaker, had both been granted similar opalescent glass patents by 1881. Opalescence revolutionized the look of stained glass, which had remained essentially unchanged since Medieval times. Early stained glasswork used flat panes of white and colored glasses, and details were painted atop with glass paints before firing. However, the paint reduced light transmission.

Tiffany sought to find natural ways to allow for gradations of depth, lines, and color—particularly in order to depict the tone and texture of human flesh without losing luminosity. The opalescent effect was so highly sought after because it enabled form to be defined by the glass itself, without paint.

“By the aid of studies in chemistry and through years of experiments, I have found means to avoid the use of paints, etching, or burning, or otherwise treating the surface of the glass, so that now it is possible to produce figures in glass of which even the flesh tones are not superficially treated, but built up of what I call ‘genuine glass’ because there are no tricks of the glass-maker needed to express flesh.”

—Louis C. Tiffany

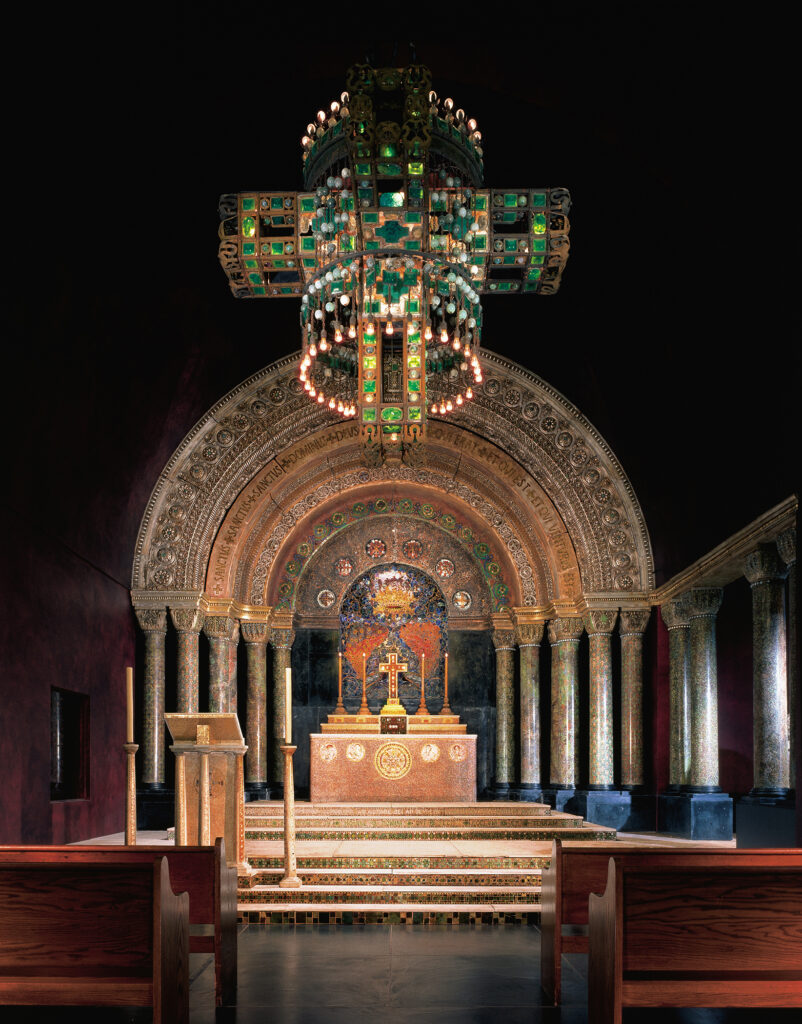

Tiffany’s newfound obsession with glass developed and proliferated after the Associated Artists disbanded in 1883. Tiffany continued as an interior designer for many years, but with a new focus on purely decorating, using glass and light. One of his most ambitious interiors was the Tiffany Chapel, exhibited in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition (the Chicago World’s Fair), which was notable for being the first world’s fair to feature electrical exhibitions. A total of 27 million visitors from all around the world came to enjoy the event.

Light filtered in through 12 leaded windows and a 1,000-pound cruciform-shaped chandelier covered in sparkling jewels and pieces of glass. Created in the Byzantine-Romanesque style, Tiffany Chapel also included 16 mosaic columns and a mosaic altar of marble and white glass. The chapel’s visual impact was undeniable, bringing Tiffany international recognition. It was reported from Wilhelm von Bode, director of the Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery) in Berlin, Germany, that the opalescent windows received more attention from visitors than any other industrial art project in the United States. Tiffany Chapel became a symbol of American ingenuity, which could rival and even surpass anything created abroad at the time.

Art for Beauty’s Sake

Tiffany’s aesthetics were based on the belief that the most beautiful and perfect design was present in the natural world and that world should therefore be the primary inspiration for art. He had an extensive horticultural library and a collection of plant photography that he commonly used for source material. His youngest daughter, Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, recalled of her father: “He knew every plant and flower. … To watch the flowers grow from bud to full bloom was his greatest pleasure.”

The fascination with nature and extending the capabilities of glass to replicate the subtle shading and lush palettes found in flowers and plants led Tiffany to explore another technique—Favrile. The term is derived from the Old English word fabrile, meaning handmade. Favrile glass is different from other iridescent glasses because the color doesn’t sit solely on the surface; it’s actually embedded within the glass.

In 1893, Tiffany hired expert glassblowers, some of whom came from the not-long-defunct Boston and Sandwich Glass Company, and established his own glass furnaces in the neighborhood of Corona, in New York’s Queens borough. From there, large quantities of his Favrile blown-glass vases and bowls could be sent to museums worldwide. In 1896, Tiffany took his new products to market, holding the first public Favrile glass exhibition at his Fourth Avenue studio in New York.

After 1900, the name Tiffany became associated with art glass, lamps, and decorative objects, more so than the formerly acclaimed stained-glass windows and mosaics. Among the items made at the time were desk sets, ash trays, enamel boxes, and jewelry. It was Tiffany’s passion that beautiful art and objects be made available to the widest audience of American homeowners. He set out to provide everyday items that he felt would enrich people’s lives with beauty and justified shifting the focus of art from public displays to household objects with the reasoning that items such as lamps, flower vases, and toilet accessories reach wider audiences than a painting might. Tiffany looked to artisans as “educators of people in the truest sense” and as masters of art appealing to emotion and the senses, thus “rousing enthusiasm for beauty in one’s environment.”

He consistently held to a traditional criterion of beauty similar to that of the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke in his treatise “On the Sublime and Beautiful,” positing that man’s concepts of beauty arise from the passion of love, the senses, the calming of nerves, and the divine providence of God. An article written by Tiffany for Country Life in America titled, “The Gospel of Good Taste” publicly shares his aesthetic views, hoping to educate and inspire a surge of beautiful art in America: “It is all a matter of education, and we shall never have good art in our homes until the people learn to distinguish the beautiful from the ugly. … We should study classic art, and learn that the simplest things are the best.”

A Dream Realized

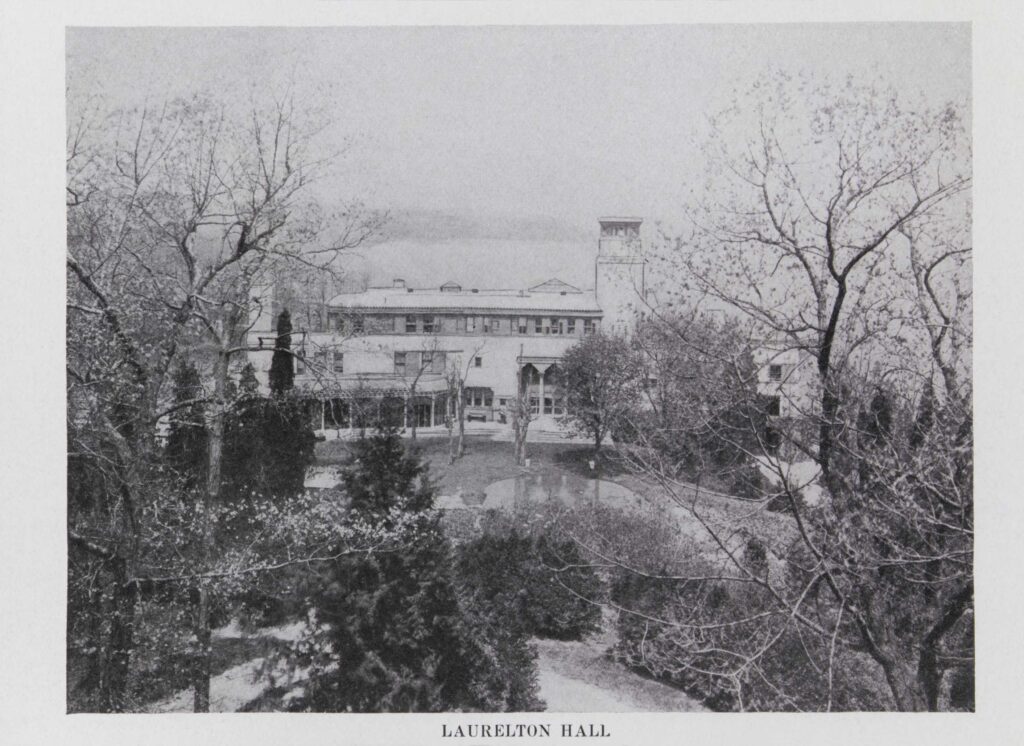

The unification of the arts and the culmination of Tiffany’s artistic and aesthetic endeavors were embodied by the final house he designed in its entirety—his own estate. Laurelton Hall was erected in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, in 1905. The 84-room property sat on 580 acres of land, 60 acres of which were devoted to the design of picturesque gardens and woodlands containing ponds, tennis courts, and a bathing beach.

The estate housed his collection of unique art gathered from around the world, as well as numerous relics designed by Tiffany Studios: furniture, lamps, windows, vases, and more. The architecture, both interior and exterior, was ornamented with glass mosaics and carved wood, inspired by art and designs from Asia and the Middle East.

The décor included wisteria-bordered long glass panels that lit up the dining room. In a sheltered alcove of the living room, Tiffany displayed several of his stained-glass windows, including “The Four Seasons,” which he cut into separate panels—the window had previously been awarded a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition and inspired the French government to appoint Tiffany a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour.

“God has given us our talents, not to copy the talents of others, but rather to use our brains and our imagination in order to obtain the revelation of True Beauty.”

—Louis C. Tiffany

Tiffany wanted to create a school of rational art (as he referred to it), where students would be shown specimens of good artwork collected from various periods and countries, fostering education in the simple, true, and beautiful. His plan for a special “museum school” was denied by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but reimagined through the transformation of his own estate, Laurelton Hall, into an artists’ retreat. In 1918, a gift of 62 acres (with several structures included) was granted to the newly established Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation. The stables were converted into dormitories and the gatehouse into an art gallery to accommodate students eager to learn the aesthetics of Tiffany’s doctrine of beauty.

Tiffany’s Legacy

Tiffany’s work and ethics resolved the conflicting ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, making an assorted range of products available to consumers of every economic level. While Arts and Crafts influencer Morris once said, “What business have we with art at all unless all can share it,” in reality, most companies couldn’t produce high-quality art at affordable prices. Tiffany, however, successfully created an art industry for all classes of people, in part because his personal wealth allowed him to sacrifice profits in the interest of advancing his artistic philosophy.

With the modernization of the United States, Tiffany’s art had fallen out of favor by the 1920s. However, after several decades of neglect the Art Nouveau movement was revived through interior design, publications, and museum exhibitions—a common aphorism is that we often scoff the arts of our parents and revive those of our grandparents. Since the turn of the century, the United States has seen the design of public buildings enhanced by ornamentation and mosaics, and many artists have begun to work in glass—glassblowing, as an art form, is more appreciated now than ever before.

Tiffany’s legacy lives on through the careful preservation of relics obtained and collected after his death in 1933. Following a fire that ravaged the abandoned Laurelton Hall in 1957, Hugh F. McKean, former artist in residence at Laurelton Hall, and wife Jeannette Genius McKean, founder of the Morse Museum, purchased what they could of the intact remains. Today, the Morse Museum’s collection of Laurelton Hall relics is the largest single collection of surviving materials from Tiffany’s turn-of-the-century estate and will likely remain a visual masterpiece of influence and inspiration for generations of artists to come.