José Angel Mayoral III is a man who lost his country. Born and raised in Venezuela, he grew up in a family of entrepreneurial business owners in Caracas. His Puerto Rican grandfather went to Venezuela as a salesman for Goodyear Rubber and Tire and decided to stay. His grandfather and father worked hard and created a GM car dealership, among many other ventures. One of them was the Fiesta Candy Company, which specialized in chocolates.

José became a part-owner and the Director of Production, and after his father opened a division of Fiesta in Spain, José was appointed as the overseas production director as well. He traveled back and forth between the two countries until 1993 when he and his wife decided to immigrate to the United States.

Venezuela was swirling with turbulence in 1993. President Carlos Andrés Pérez had just been impeached for corruption, and Hugo Chávez had initiated two coup attempts the year before. Doing business in Venezuela was hampered by graft and the constant greasing of palms to get anything done.

In José’s experience, Spain in 1993 was also a terrible place to do business. Felipe González Márquez was the Prime Minister and the Secretary-General of the dominant Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE). The environment was decidedly unfriendly toward business. Business owners were seen as the oppressors, and local legislators, officials, and unions were frequently in opposition.

There were three unions, run by the socialists, the communists, and the anarchists. José recalls:

We had a constant barrage of strikes, sabotage, all sorts of problems. They would sue us constantly. The judges were always siding with the unions because they were afraid. The police would not enforce the laws and break down the pickets. On any particular day, you would arrive at the parking lot to get your car and find that everybody’s tires had been slashed. It was very negative.

The anarchists were the only ones that you could negotiate with because all they cared about was, “Hey, are you going to pay me more money?”

The others wanted all sorts of concessions. Whatever dictum came from Moscow; that’s what they wanted.

In that hostile environment, José and his American wife Laurie decided to move to the United States. José was fortunate to find a position as the Sales Director for Latin America and the Caribbean for Lamb Weston, which at the time was part of ConAgra Foods. They moved to Boca Raton, Florida, since José had to travel south so frequently. He was deeply impressed with the people who ran Lamb Weston and said:

They were fantastic people. I was so surprised to see the level of professionalism and the human quality that these people had. The way they ran the company was absolutely in a Christian way. They treated people like souls. They were incredible people, and the company was fantastically successful.

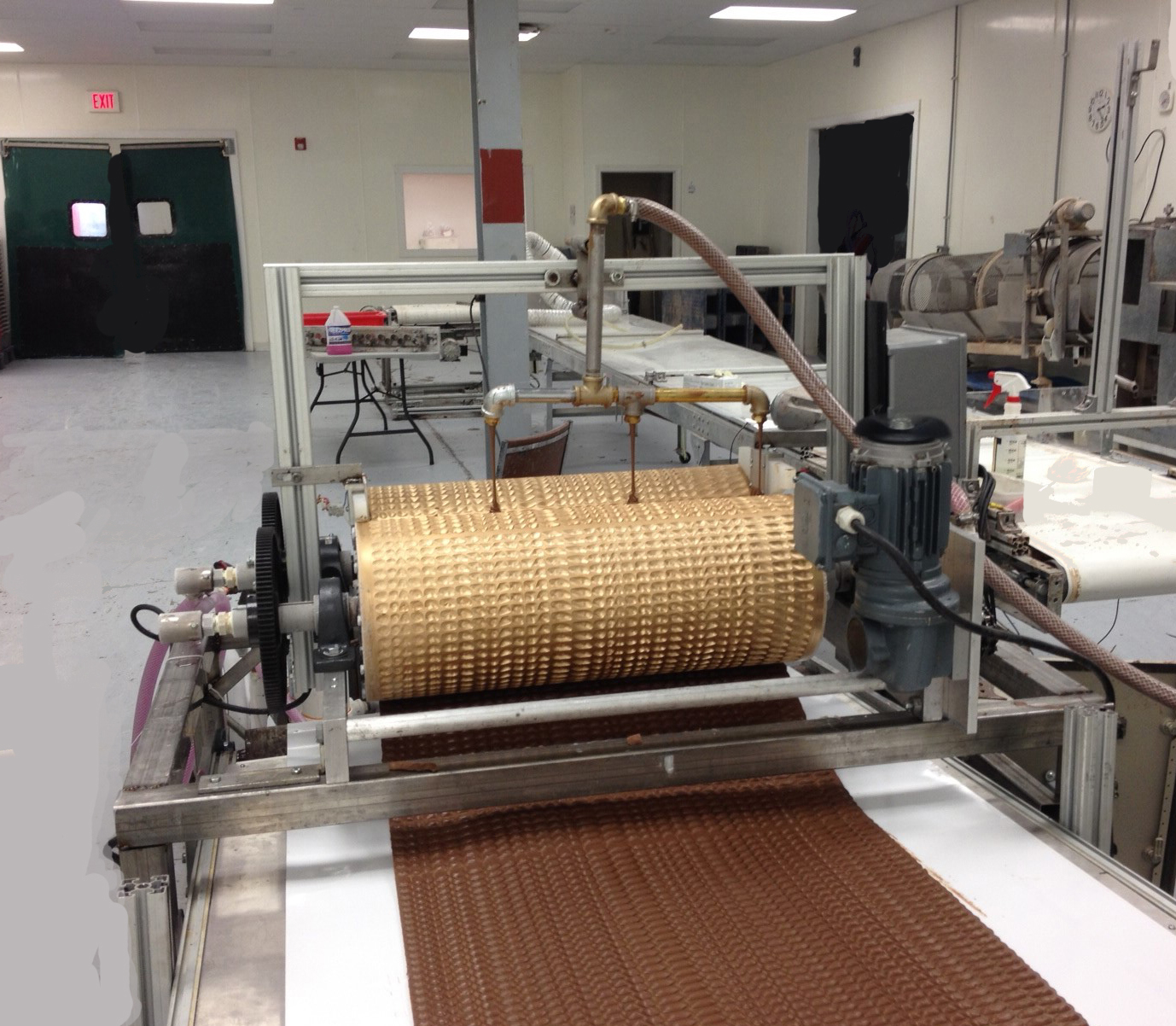

In 1997, the same year that Hugo Chávez founded a democratic socialist party called the Fifth Republic Movement, José and Laurie moved to York, Maine, and established a branch of the Fiesta Candy Company across the border in Rochester, New Hampshire. It’s now called Great Bay Chocolates1 and employs six people.

As Venezuela was collapsing under the Chávez regime, and as José’s family businesses in Venezuela with their many employees were going under, José and Laurie were building a new business in an environment that was proof positive that the American system of free enterprise worked better than totalitarian socialism.

José was astonished and grateful at the friendly attitudes and substantial help that the citizens and town officials in Rochester extended to them. The town helped with loans and did everything they could to get the candy company off the ground. The differences between his experiences in America, Spain, and Venezuela were enormous.

He reflected about the standard of ethics in Venezuela and America, and the refusal of local officials in America to take bribes, and their genuine desire to help others.

Every time the fire alarm goes off in the building and the cops come over, and you try to give them a bag of candy, they refuse it. These people do their jobs and try to help you. The health inspectors are here to help. The mayor wants the business to thrive. I haven’t seen any corruption whatsoever.

Don’t make me look like a hero because I’m not. It’s the country of America that is the hero. It’s the town of Rochester and the local officials that basically run the day-to-day and the people that make it easy to get businesses going.

José’s father sent them $50,000 worth of equipment from their factories in Venezuela and Spain under a long-term loan. The Fiesta Candy Company in Venezuela was taken over by the government, and the company’s branch in Spain eventually went bankrupt. But the company lives on in a small town in New Hampshire. José and Laurie have two sons, and one son works at the company, continuing the family tradition.

When José talks with his relatives in Venezuela, he’s deeply saddened by the increasingly grim news about the tragedy of socialism. His two cousins, Diana and Federico, are still there, taking care of the GM car business that has no cars. Now, it only does repairs. They’ve informed José that the people who are left in Venezuela have become resigned to their fate. The political opposition to President Nicolás Maduro is ineffectual. Millions of citizens have fled: to Columbia, to the United States, and other locales.

José Angel Mayoral did indeed lose his beloved country of Venezuela, once the wealthiest country in Latin America. His solace is that he has been blessed with a new one. His gratitude toward America is profound, and his experiences send a clear message to his adopted country: Don’t become like Venezuela.

Peter Falkenberg Brown is a writer, author, and public speaker. One of his recent books is titled “Waking Up Dead and Confused Is a Terrible Thing: Stories of Love, Life, Death, and Redemption.” He hosts a video and podcast channel called “The FalkenBrown Show” at his website peterfalkenbergbrown.com