“The earth is not a mere fragment of dead history, stratum upon stratum like the leaves of a book, to be studied by geologists and antiquaries chiefly, but living poetry like the leaves of a tree.” This living poetry was what led to Henry David Thoreau’s philosophy for life.

By most, Thoreau is considered one of America’s great 19th-century writers, but it would be nearly impossible to read his work without also thinking of him as one of its great 19th-century philosophers. Of his many works, none captures his philosophy as well as his “Walden; or, Life in the Woods.”

Thoreau didn’t simply espouse his philosophy. He lived it.

‘I Wished to Live Deliberately’

Thoreau lived in the northeast part of the country during the early to middle part of the 1800s. His home was in Concord, Massachusetts, but his abode was of his own making—at least, for a period of time. The writer and naturalist explained: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. … I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.”

He believed there was only one way to accomplish this, and that was to venture far from the people of his town and live in Walden, among woodland hills that surrounded a large pond. Though beautiful, he noted that the scenery was of “a humble scale.” Interestingly, Walden, with its simultaneous beauty and humility, was a reflection of Thoreau’s philosophy. His idea was to live humbly within the beauty that nature presented: the wildlife, the change of seasons, the hardships, the solitude.

His philosophy was an exercise in self-reliance that focused on the three essential elements of food, water, and shelter. Fresh water was readily available to him with the pond’s deep well, except of course when the pond froze in the winter and required that he use his axe and pail and go in search of water. His food was either provided by nature or by his own efforts—gardening, fishing, picking wild berries, hunting small animals—and, as well, infrequent visits to town.

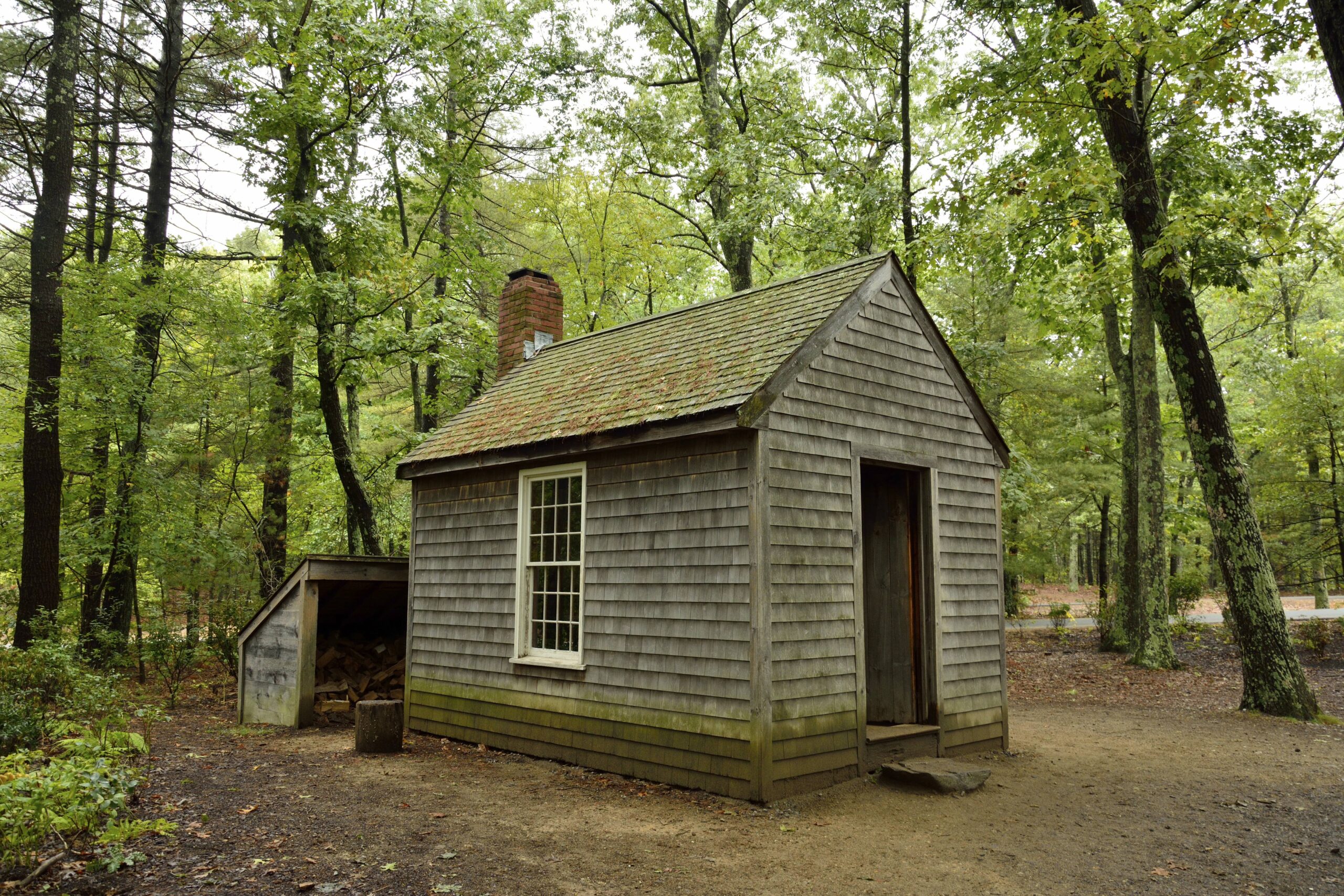

His shelter took more time, but he was supplied with lumber from the woods. He began chopping down trees at the end of March 1845, and by July 4 he had occupied the “palace of his own”—furnished with table and chairs, flooring, and a fireplace all of his own making, and what he viewed as ever-changing transcendent artwork.

“When I see on the one side the inert bank—for the sun acts on one side first—and on the other this luxuriant foliage, the creation of an hour, I am affected as if in a peculiar sense I stood in the laboratory of the Artist who made the world and me—had come to where he was still at work, sporting on this bank, and with excess of energy strewing his fresh designs about.”

Poverty as Wealth

There was little doubt that the naturalist writer was different. His transcendentalist views, a movement that originated in New England, caused him to stand out. More than that, however, Thoreau desired to be a man apart. Despite his beliefs about humanity and nature, he, much like most anyone, had questions that only a trial could answer. What could he endure? What were the necessities of life? What was poverty and what was wealth? What was true philosophy and what was true economy?

Thoreau wanted to live well, although not in an economic sense. His view of wealth was concentrated on necessity and simplicity, and even morality.

“Give me the poverty that enjoys true wealth,” he boldly stated. “No man ever stood the lower in my estimation for having a patch in his clothes; yet I am sure that there is greater anxiety, commonly, to have fashionable, or at least clean and unpatched clothes, than to have a sound conscience.”

He witnessed anxiety in his neighbor (neighbor being a relative term, as most people lived at least a mile from him) whose desire for luxury items, like butter, coffee, and tea, caused discontentment. To Thoreau, his neighbor’s cycle of work-spend-work was so labor-intensive that the results hardly seemed worth the effort.

“Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life?” he asked. “We are determined to be starved before we are hungry.”

“Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed and in such desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.”

The Beat of a Different Drum

Thoreau believed that every man should be able to choose his own path, which was what he viewed as the makings of the “true America.” It bothered Thoreau that his neighbor had so little to show for his labor, while he himself labored little and showed nearly the same result. But it did not matter enough to him to force the issue. “Let everyone mind his own business, and endeavor to be what he was made,” he wrote.

Thoreau heard a drummer that many, if not most, could not hear. He noted that the problem was that people were listening to the same drummer, and it was the drummer of “public opinion.” And public opinion was often tied to what is new rather than what is valuable.

“One generation abandons the enterprises of another like stranded vessels,” he wrote, and then added, “Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new.”

For Thoreau, espousing a philosophy meant more than empty words; it should be a guide for living. He was a philosopher who lived his philosophy, while some, he believed, simply philosophized. He felt there was something tragic about that, as it not only caused the philosopher to not truly live, but also caused harm to those who were taught such philosophies.

Leaving Walden, and a Challenge

On September 6, 1847, Thoreau left Walden, having spent more than two years living out his philosophy “to live deliberately.” He endured the harsh New England winters and enjoyed its beautiful springs. He discovered what wealth truly was, at least for him. He realized what he could endure and he embraced the peace of solitude. For a transcendentalist, “Walden” was his magnum opus, connecting his spiritual beliefs, his love of nature, and his personal philosophy. It is hard to miss the connection when he recollects his walks through the “laboratory of the Artist.”

Sometimes I rambled to pine groves, standing like temples … so soft and green and shady that the Druids would have forsaken their oaks to worship in them; or to the cedar wood … where the trees … spiring higher and higher, are fit to stand before Valhalla, … and make the beholder forget his home with their beauty, and he is dazzled and tempted by nameless other wild forbidden fruits, too fair for mortal taste.

The work of “Walden; or, Life in the Woods” calls into question our own philosophies. What are they, and do we believe them? And if we believe them, do we live them? The Roman poet Horace famously wrote, “Carpe diem” (“seize the day”); Thoreau’s call is an echo of that. It is a call “to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life,” no matter the situation.

“However mean your life is, meet it and live it; do not shun it and call it hard names,” Thoreau wrote in the final pages of his great work. “Love your life, poor as it is. You may perhaps have some pleasant, thrilling, glorious hours.”

From January Issue, Volume 3