In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Consuelo Lippi would stand at the counter of her hat store in St. Augustine, Florida and tell the suited-up salesmen of the hat trade that she was indeed the owner of the Panama Hat Company.

They would look her up and down and declare, “No, no, no. You are the missis. I need to talk to the owner. I need to talk to your husband. You are the missis.”

She would respond and say, “Yeah, I’m the missis, and I’m going to pay you for your merchandise.”

She said it took a number of years to establish her credibility because, at that time, the hat trade was dominated by men.

“I had to fight really, really hard with businessmen, but I did eventually gain their respect. Later on, they would come and be more open with me because they knew I understood what they were talking about.”

Lippi understood because she had thoroughly researched the process of making Panama hats in her native Ecuador. And yes, Panama hats are not from Panama—they only bear that name because they were sold in vast quantities through the country of Panama to the world. In Ecuador, they’re more correctly known as sombreros de paja. They’re woven from the leaves of the Carludovica palmata plant, known in Ecuador as the toquilla palm.

The plants are evergreen shrubs that grow to around 12 feet tall on the western side of Ecuador. The stems yield a unique fiber that is then woven into varying degrees of coarse or ultra-fine material referred to as the “hat body”—a floppy dome of palm fibers that is then shaped and blocked by experts to produce a finished Panama hat.

The toquilla palm plants are in decline in Ecuador, along with the number of weavers. There are only around a dozen Panama hat artisans left who know how to weave a “super fino” Montecristi Panama hat. Many of the weavers have left Ecuador for higher rates of pay in other countries. Lippi stated that the genuine Panama hat might be extinct by the middle of this century.

As someone who has fallen in love with Panama hats and was tremendously pleased with the quality of the hat that I purchased from Lippi’s son, Tony, I found her prediction dismaying. I sincerely hope that the Ecuadorian people can save the Panama hat.

Although there are many companies selling Panama hats in America, the small shop in St. Augustine stands out, not just because of its location in a historic town founded in 1565, but because of the quality of its merchandise, its extremely loyal customer base, and the unique story of its founding, growth, and results.

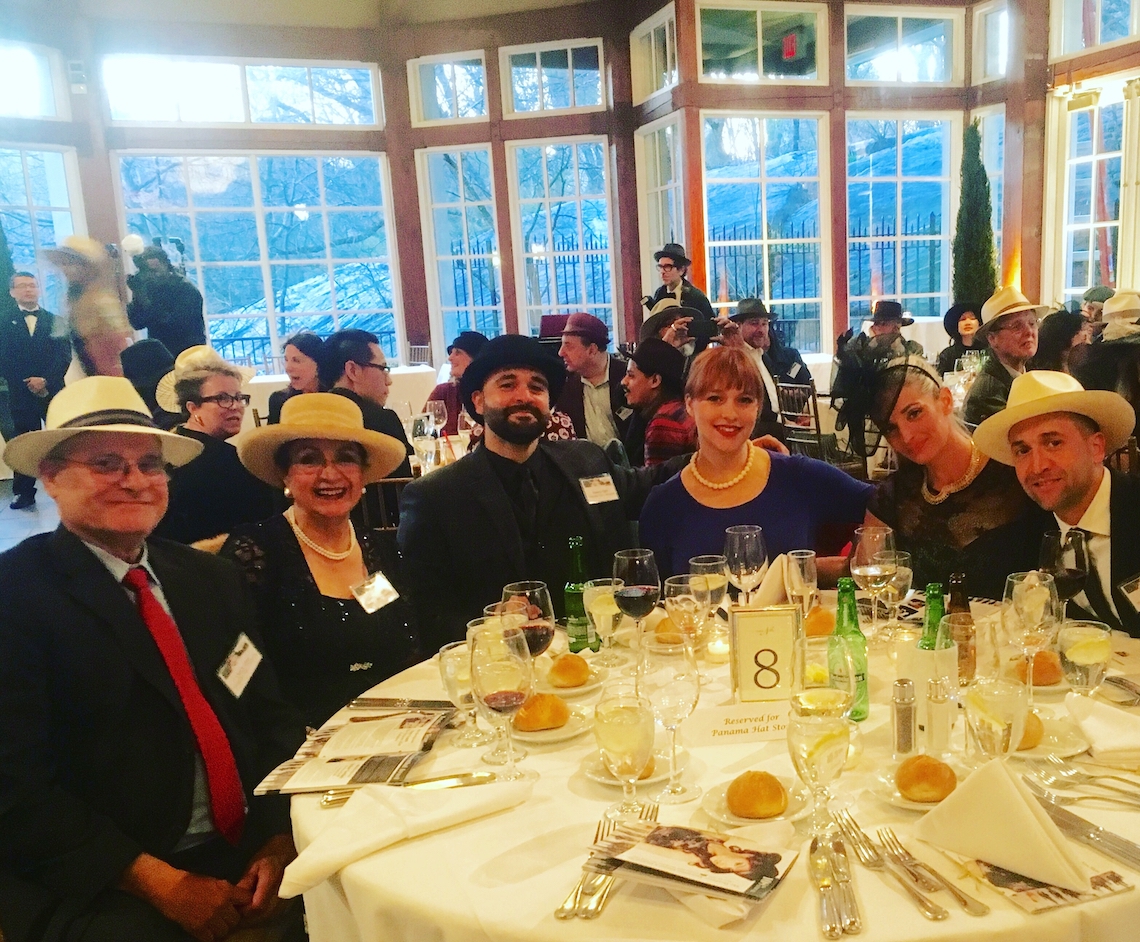

In 2016, in the Boathouse in Central Park, New York City, the 112-year-old Annual Headwear Association gave their prestigious Retailer of the Year Award to the Panama Hat Company. The vote by the Board of Trustees was unanimous. One of the criteria for the award was the volume of merchandise sold in relationship to the store’s size. Lippi and her eldest son, Tony, received the award and were joined at the event by Lippi’s husband, Chuck, their younger son, Danny, and their daughters-in-law, Cat and Braiden.

Tony had joined the business in 2003 as a co-owner with his parents and now manages the store for Lippi, who is still going strong in her seventies. Their clientele includes a broad and interracial base of people who love Panama hats and is highlighted by famous names like the trombonist Richie “La Bamba” Rosenberg and His Excellency Ramón Gil-Casares, the Spanish Ambassador to the United States who came to St. Augustine in 2015 for the city’s 450th commemoration of its founding.

After 36 years, the Panama Hat Company is a success. It employs between 15 and 20 people and is a fixture in St. Augustine. But, like many family-owned businesses, its birth was unexpected, and its growth was not guaranteed.

Lippi and her husband, Chuck, had arrived in St. Augustine in the 1980s. They met at a Peace Corp conference in Ecuador in 1968 when they were in their 20s. Chuck was a Peace Corps volunteer, and Lippi was a high-school teacher from the town of Ambato in the central province of Tungurahua, hired by the Peace Corp to teach Spanish to the volunteers.

They fell in love, married, and came to America, where Chuck established a career as an arborist, and Lippi expanded her career, teaching Spanish and the theory of teaching languages at Flagler College in St. Augustine. She also taught technical and conversational Spanish at the Mayo Clinic and continued teaching at Flagler for almost 20 years.

St. Augustine and its rich Spanish history spoke to Lippi, and in 1985 she decided to rent a room in the Arrivas House, a historic landmark dating back to the mid 1600s. She purchased a number of Ecuadorian items, including some Panama hats, and offered them for sale. She was surprised at how quickly they sold and was even more astonished when Robert L. Gold, at that time the executive director of the Historic St. Augustine Preservation Board, offered to rent her the entire building, on the condition that she maintain the quality of her merchandise.

It was a significant honor that Lippi deeply appreciated and one that produced a certain amount of panic since she wasn’t quite sure how she would maintain a much larger venture.

The next day she was on a plane to Ecuador to research and procure products in the famous market town of Otavalo. She walked through the market, following American tourists, and watched what they purchased. She then bought similar items to bring back to the Arrivas House, to her new business that would become the Panama Hat Company.

Many research and investigative trips to Ecuador followed over the years, with Chuck and Tony driving on broken, dusty roads deep into the interior of Ecuador to reach the remote villages where the toquilla hats were woven. Lippi and Tony learned from the experts how to block the hat bodies into high-quality Panamas and eventually brokered an arrangement with a hat blocking company in America so that they could scale their merchandise for volume.

It’s been a long journey of hard work and commitment for Lippi, a woman who started a business in a world where hatters were mostly men. She has done that work for something much more important than money. She told me:

“I don’t value the dollars as much as I value the praise that we get from my customers when we sell them an item that is genuine and is something that they will remember from my country, Ecuador. I am extremely proud to sell something that I know they are going to enjoy for the rest of their life.

“I have so much respect for the two countries that have been so gracious to me, and so generous—my country Ecuador and the United States. And… we have the best customers and the best employees, ever.”