Erika Obando, 47, was 5 years old when she was smuggled from Colombia through the Bahamas to Miami by her parents. The family was subsequently detained. At the time, however, Obando recalls that police officers did their jobs with empathy and compassion.

“They saw where we came from,” Obando said. “These were officers who were arresting families en-route, so I guess being part of that experience moves you in a way. I have no idea what’s going on today but there is definitely a lack of empathy.” Back then, Obando said children were not separated from their families when they were caught illegally entering the U.S.

“We stayed in a facility that catered to families where the women and children stayed on the first level and the men, whether they were fathers of a family or single, lived on the second and third floor,” Obando said in an interview. “Twice a day, we had the ability to meet in the courtyard with my father. We were also allowed to eat all three meals with both my parents present.”

Obando became a resident in 1987 during Ronald Reagan’s amnesty program and eventually a United States citizen in 1997. The family settled in Elizabeth, New Jersey where Obando faced another obstacle.

“I was beaten quite often by my mom,” she alleges. “She was a severe hoarder and so the conditions of the home were detrimental. My mom and dad would fight all the time because my dad didn’t want those conditions and my mom had an illness, which turned into severe depression. The living conditions were atrocious and I would receive the brunt of her anger.”

Obando escaped at the age of 14 after confiding in a friend who was becoming a nun about her home situation.

“I didn’t want to tell the authorities because I was afraid of what would happen to my parents,” she said. “My friend told me about a home next door to a convent that catered to women who didn’t have anywhere to stay.”

The nuns who managed Home of Nazareth, which was located less than a mile from Obando’s family home, offered Obando shelter after she explained the situation.

“My dad ended up signing me over for the nuns to rightfully care for me on a temporary basis and to stay at their house,” she said. “I lived there for two years.”

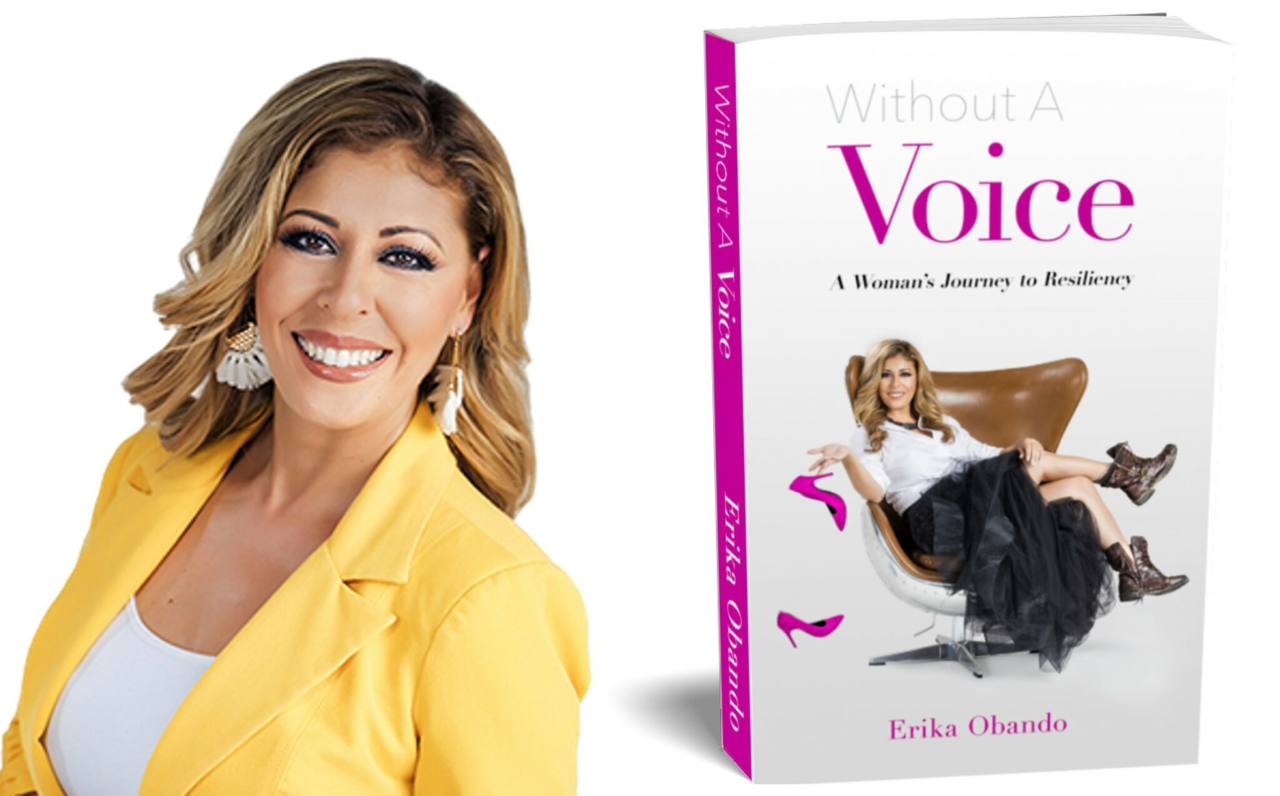

Obando graduated from high school, married and had a child. Today, she lives in Fort Lauderdale, Florida and works as an author, lecturer, and advocate for at-risk teen girls with organizations such as the Pace Center for Girls Broward, Women of Tomorrow, Johnson & Wales University, Lynn University, and Junior Achievement of South Florida.

“I feel like I have a responsibility,” she said. “I didn’t go through all that to say it at a party or at a bar. I went through that because there is a purpose for me at the end of the day and that is for me to give back and help empower people who feel like they just can’t keep going. I’m here to show and tell them that ‘Yes you can go on.’”

Obando uses the book “Without a Voice: A Woman’s Journey to Resiliency,” which she wrote and self-published in Nov. 2020, to teach during coaching sessions with others.

“I empower the youth,” she added. “I am part of a lot of nonprofits here that particularly cater to young women in at risk situations. They bring me in as a mentor so I can help them through different challenges like depression or anger management and I teach life skills.”