Talmage Boston: The name rings of American history. A lawyer by trade, Mr. Boston has written his way into the society of historians. As one of Texas’s finest litigators, he shares a connection with those early Americans whose lives he studies. Nearly half of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and more than half of those who signed the Constitution were lawyers.

From Yankee Stadium to the White House, Mr. Boston has written five books that connect with modern Americans on both cultural and political levels. His latest work, “How the Best Did It: Leadership Lessons From Our Top Presidents,” is not only a recollection of the country’s best presidents from George Washington to Ronald Reagan, but it is a propositional work for current and future leaders.

In this conversation, Mr. Boston stated that “How the Best Did It” is a work of “applied history” that encourages readers to do more than “enjoy history,” but to “actually apply it to what you are doing in your daily life.” Digging into the lives, methods, and decisions of the top presidents―Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Reagan―Mr. Boston has unearthed a treasure trove of qualities, disciplines, and skills that every leader should know and apply.

American Essence: What are some of the common qualities that you noticed in the eight presidents?

Talmage Boston: I found three common qualities: One, they were all great persuaders. Some were great persuaders because they were eloquent orators. Some were great one-on-one, personal persuaders. One way or another, they moved the needle with whomever the audience was in their particular era. Two, they were all self-aware. They each had an awareness of his strengths and weaknesses. They always found ways to use their strengths. Where weak, they would bring in colleagues who were strong and allow them to take charge. Three, they all succeeded in their eras because they targeted the middle way―the great middle. They were smarter than to target the extreme right or the extreme left. They knew that was never going to accomplish anything positive. Their efforts and messages were always in terms of what the vast American middle was inclined to think on an issue.

AE: People often “want” to be leaders but don’t understand or don’t want to accept the weight that comes with responsibility. What can readers learn from your book about the demands of leadership?

Mr. Boston: For each of my chapters on the eight presidents, I identify his three most important leadership traits that caused him to be successful … a total of 24 leadership traits. But at the end of each chapter, I ask a series of questions for the reader to ask him or herself. Essentially: “How am I doing in the trait I just read about? How am I learning from my mistakes? How am I doing on unwavering integrity? How am I doing in building consensus out of factions that are trying to split the organization? How am I inspiring optimism throughout my organization?”

These leadership traits are timeless and can be applied in any generation and basically any circumstance.

AE: Leaders are often accused of surrounding themselves with yes-men. Why is it important for leaders to surround themselves with people who are industry- or subject-knowledgeable, confident enough to be disagreeable, but also buy into the leader’s overall vision?

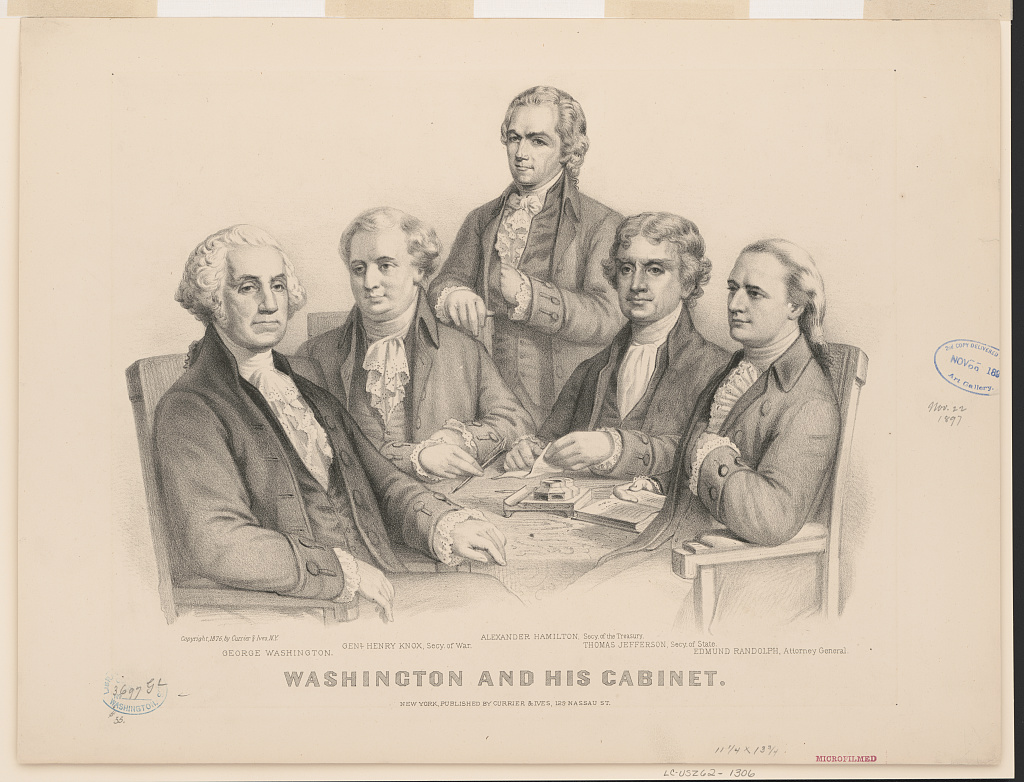

Mr. Boston: Washington is a great example. He knew going into the Constitutional Convention, [they] were basically going to create a government from scratch and to do that you had to have a deep knowledge of history, different types of governments, and what had worked and what hadn’t. He couldn’t have studied quick enough to draw any sound conclusions, but he knew James Madison had, so he delegated the responsibility of what became known as the Virginia Plan―essentially the backbone of the Constitution. With a brand-new country, we had postwar debts and we had to figure out how to make the economy work. Washington had never studied economics or fiscal policy, but Alexander Hamilton was a financial genius, so he turned that responsibility over to him, and Hamilton did a great job.

Lincoln was famous for his team of rivals [in his cabinet], three of whom had run against him for the Republican nomination. Two, Edward Bates and William Seward, immediately recognized that Lincoln was the smartest guy in the room. So, they became his biggest fans. Salmon P. Chase, who was something of an egomaniac, never could quite acknowledge it, but nonetheless he was a brilliant guy, and ultimately Lincoln named him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Eisenhower had cabinet meetings every single Friday. As a rule, you couldn’t bring up any issue that pertained to your department. He wanted to talk about big issues. He wanted free exchange, debate, and disagreements. He wanted to hear it all. He didn’t want to make the final decision until he knew he’d considered the soundest and strongest viewpoints on all sides of the issue. That’s how Eisenhower was so effective in making good decisions.

AE: You discuss Washington’s self-criticism. You also reference Eisenhower, who once said, “Always take your job seriously, never yourself.” What was the benefit of self-criticism for these presidents?

Mr. Boston: You can’t just go through life on cruise control, thinking, “Everything I do is great. Every decision I make is wise.” Not many people like to be on the receiving end of criticism from others, but a self-aware person can acknowledge his own flaws and areas that need improvement, and then diligently go about the process of making himself better. That’s how you become the best that you can be, and all eight of these presidents became the best that he could possibly be through this rigorous self-examination and fierce desire to be better tomorrow than he was today.

AE: All of these presidents were able to communicate at a high level for varying reasons—either by speech or writing or by virtue of their body of work. How did trust and credibility contribute to these presidents’ capacity for effective communication?

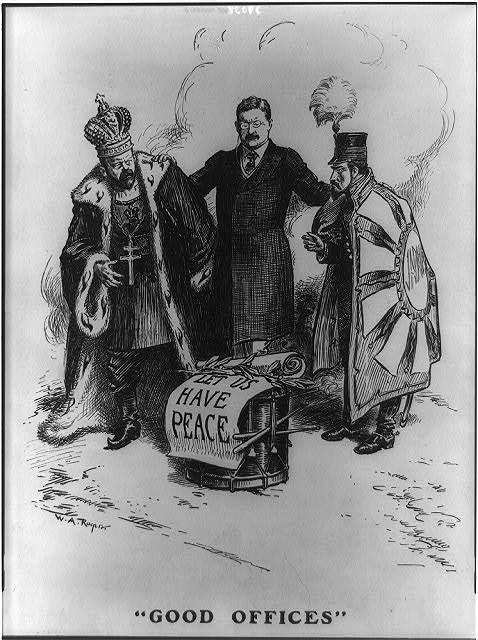

Mr. Boston: It’s virtually impossible to be an effective leader if you don’t have strong credibility, which is tied to your integrity. In terms of Theodore Roosevelt, he had this ferocious egotistical personality, but it had a certain charm and appeal to it. He was probably our highest IQ president. He was not a great public speaker. But his real skills as a persuader were demonstrated as a mediator, like the Great Coal Strike one year into his presidency. Winter was coming. People didn’t have coal. No American president had ever gotten involved in a labor dispute. Roosevelt said, “If I don’t do it, then it’s not going to happen and we’re going to have half the country freezing to death.” So, he got both sides―the workers and owners―together [and] created a dialogue. Together. Separately. Listening. Talking. Brainstorming. He finally came to the approach of binding arbitration on the issues involved, and they agreed to it, which ended the strike.

A [few] years later Japan and Russia were at war and they couldn’t find a way to bring an end to it. They reached out to President Roosevelt. He got that settled, and for it he won the Nobel Peace Prize. … Later he settled a dispute in Morocco. A [year] after that, he settled a dispute at the Hague Convention. With Roosevelt’s power personality, his brilliance, his emotional intelligence of getting people to do the right thing without pissing them off, these were his skills as an up close and personal communicator that caused his presidency to be so successful.

AE: John F. Kennedy was young and rather inexperienced politically. What made him such an effective leader?

Mr. Boston: The traits that made Kennedy stand out as a great leader that I think are important for anyone who aspires to be a great leader are, one, he was an amazingly quick study, who created great policies in three major areas in a short period of time. Two, he was calm in a crisis, and three, his ability to not only be an eloquent speaker, but for his words to inspire action―positive action.

In his first inaugural address, he said, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” A couple of weeks went by and he proposed the Peace Corps. Soon tens of thousands of young Americans joined the Peace Corps, and they went abroad and enhanced American PR all over the world. A year later, 1962, we were involved in the Space Race in the post-Sputnik era. Kennedy at Rice Stadium in Houston gave the famous speech where he said, “I want to send a man to the moon in this decade. And we’re going to do it not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard.” Those words, Congress heard them; all of a sudden they’re willing to spend money on the Space Race, and lo and behold we did get a man on the moon by the end of the decade. And then his speech after the Birmingham Riots awakened our conscience and reoriented the members of the House and Senate on the imperative of having a strong civil rights bill. All these positive things come out of his powerful speeches. Those are the traits from Kennedy that standout despite serving less than three years.

AE: You wrote: “Most people with ambition aspire to lead.” Ambition is often given a bad name, often tying it to famous leaders like Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon Bonaparte. How do you dispel the connotation that ambition is for the unscrupulous or power-driven?

Mr. Boston: Ambition can be for the unscrupulous or power-driven, but it’s also for people with good hearts and good moral compasses who simply want to be the best they can be. They have the basic human desire to want to be recognized and are willing to take on the public responsibility of governing. None of the presidents were unambitious. You don’t go through this process of elections, developing relationships, dealing with the negatives, and doing all that it takes to become the president of the United States unless you’re wildly ambitious. That doesn’t mean you’re going to be unprincipled or thoughtless. It just means you want to get to the top and in order to get to the top, you want to be the best person you can be. These presidents hit that mark.

AUTHOR NOTE: Mr. Boston’s selection of the eight presidents is based loosely on the two most recent C-SPAN Presidential Historians Surveys.

From Sept. Issue, Volume IV