When a young U.S. Army lieutenant named Zebulon Pike set out to explore the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains in 1806, he was unceremoniously arrested by Spanish troops in modern-day Colorado. The Spaniards marched him at gunpoint through northern Mexico (including today’s New Mexico and Texas) before deporting him to Louisiana. Isolationist Spanish authorities thus jealously guarded their frontiers against perceived American incursions.

Only a few years after Pike’s journey, however, Mexico erupted into revolution. What this development might mean for American traders, no one could say. Regardless, a vast, largely uncharted buffer territory yet separated Mexico proper from the United States. From the Missouri border, hundreds of miles of plains—inhabited by bands of highly mobile and often hostile American Indians—ran up against hundreds of miles of desert and mountains. All of this must be traversed before one could ever catch a glimpse of Santa Fe.

Enter William Becknell. Becknell had lived in Missouri for around a decade, making his way further and further west until finally setting himself up on the Missouri River—the state’s western border. A veteran of the War of 1812, Becknell worked a farm, traded horses, and operated a ferry across the Missouri at Arrow Rock. Later, he tried his hand at salt mining, and he speculated in land, too. To carry out his various enterprises, Becknell borrowed a sizable amount of money.

Spurred by Debts

Then came the Panic of 1819. Monetary inflation, much of it in the form of unredeemable paper money, drove gold and silver coin into the hoarder’s cache. Businesses shuttered. Banks collapsed. Loans were called in and credit contracted—and Becknell’s creditors demanded payment in gold or silver. How would he come up with the money?

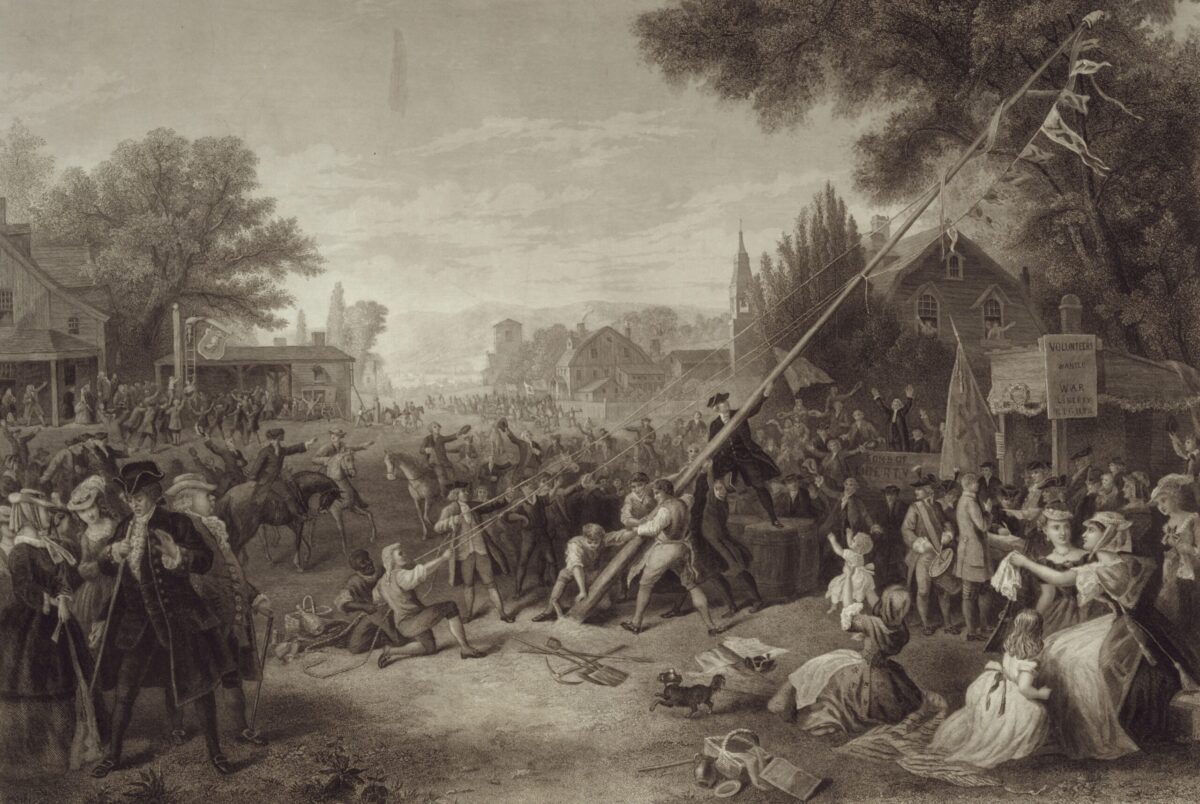

The standard hard-money unit circulating in the United States at the time was the Spanish dollar. Due to the Panic, these were now in very short supply. Becknell determined, then, to head west, deep into Spanish-controlled territory, to see if he could trade for silver coin. In August 1821, he placed an advertisement in the local newspaper. “W. BECKNELL” was captaining “[a] Company of 17 men … destined to the westward,” the notice read. The party hoped to increase its ranks to 30. “On the first day of September the company will cross the Missouri at the Arrow Rock,” the notice informed its readers. Any who wished to join were instructed on where and when to meet.

But when the prearranged day arrived, only a handful of men—perhaps five—showed up prepared for the journey. Including Becknell himself, then, the company may have numbered a mere six.

Moving in a southwesterly direction, Becknell’s company crossed the plains of Kansas—meeting virtually no natives along the way—to the Arkansas River. Continuing west along the Arkansas, Becknell turned southwest again at the much smaller Purgatoire River (thereby missing Pike’s Peak by about 160 miles). The stream led them to an offshoot of the Rockies. The journey through these mountains was difficult, but on the other side, Becknell and his company were greeted by a fantastical landscape of desert mesas, buttes, and canyons.

Reception by the Mexicans

Continuing southwest about 100 miles, the men suddenly encountered a contingent of 400 Mexican soldiers traveling in formation. They were led by a captain named Pedro Ignacio Gallego.

This was the moment of truth. Would this agent of the state, with a veritable army at his back, confiscate the Americans’ goods, deport them, or imprison them—as had been done to explorers and would-be American traders in the past?

As it turns out, Gallego had been sent on patrol not to seek out trespassing Americans, but rather to counter a recent wave of violent raids by the Navajo and the Comanche against Mexican settlements in the area. Indeed, Gallego at that very moment had been tracking a marauding band of Comanches when he’d spotted Becknell and his company. In his diary (translated here from the original Spanish), Gallego later described the meeting with Becknell:

“About 3:30 p.m. encountered six Americans at the Puertocito de la Piedra Lumbre. They parleyed with me and at about 4 p.m. we halted at the stream at Piedra Lumbre. Not understanding their words nor any of the signs they made, I decided to return to El Vado.”

Becknell’s own account of the meeting adds more detail:

“On Tuesday morning the 13th, we had the satisfaction of meeting with a party of Spanish troops. Although the difference of our language would not admit of conversation, yet the circumstances attending their reception of us, fully convinced us of their hospitable disposition and friendly feelings.”

The meeting was thus an amicable one, despite the language barrier, and Becknell came away convinced of the Mexicans’ “manifestations of kindness.” The two groups camped together that night, and the next day traveled together, too. Entering a town, a “grateful” Becknell noted that its inhabitants exhibited “civility and welcome.” It is likely that Becknell then learned of Mexican victory over the Spanish in their revolution. Mexico was independent. From here, the Americans were allowed to continue their journey on their own.

Trading in Santa Fe

In the middle of November, some 77 days after departing Missouri, Becknell and his men finally entered the town of Santa Fe. The new governor of New Mexico, Facundo Melgares, who had also been the old governor of Spanish New Mexico, was the same man who had arrested Pike 15 years earlier! Melgares personally welcomed Becknell and his men, informing them that Mexico was open for business.

Becknell spent several weeks trading with the highly receptive inhabitants of Santa Fe, offering calico cloth and other items from the States for Spanish dollars. On the way home to the United States, he traveled in a direct northeasterly direction (rather than following east-west or north-south river trails), which avoided mountains altogether in favor of a mostly flat, level path: the imposingly dry Cimarron Desert. Fortunately, the Cimarron River provided something of a watery path through this otherwise sand-sage country, though the river sometimes dried up completely.

Five months after his initial departure from “the Arrow Rock,” Becknell crossed back into Missouri, his saddlebags filled with Spanish silver. A few hundred dollars’ worth of trade goods had been swapped for around 6,000 dollars in hard coin. His debts could now surely be paid—indeed, several times over!—with money to spare.

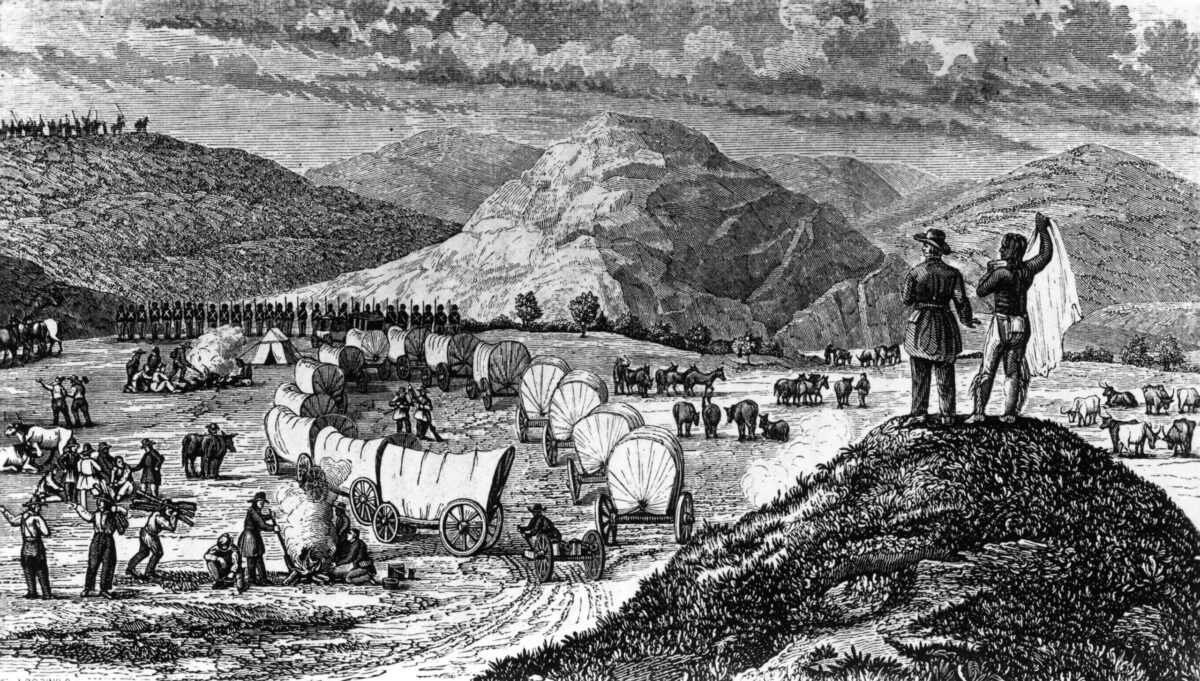

But Becknell wasn’t finished. The next year, he returned to Santa Fe—this time, of course, opting for the Cimarron route. Crucially, he brought with him several covered wagons, the first ever to cross this territory. The trip took just 48 days, and apart from an ordeal involving the Osage Indians—who kidnapped three of Becknell’s party and tortured them before the Missourian managed to get them back—it appears to have been uneventful. Later accounts that Becknell and his men at one point almost died of thirst, only surviving by sucking the liquid contents out of crudely removed animal stomachs, are of questionable authenticity. In any case, Becknell and company returned home from this second trip having earned 3,000 percent profits.

Becknell had blazed the Santa Fe Trail. Later, he would help map it as a surveyor and guide. And for the next 60 years, it was some variation of Becknell’s wagon trail upon which countless travelers and traders moved goods between New Mexico and the East.

Dr. Jackson, who teaches Western, Islamic, American, Asian, and world histories at the university level, is also known on YouTube as “The Nomadic Professor.” You can follow his work, including entire online history courses featuring his signature on-location videos filmed the world over, at NomadicProfessor.com.