George Washington, universally acclaimed nowadays as one of our best presidents, encountered a little bad press in his own day. Even before his inauguration, he knew that facing impossibly high expectations would be a challenge during his time as president.

“My movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.” These were the unenthusiastic words of George Washington, written to fellow Revolutionary War veteran Henry Knox on April 1, 1789, not long before his nearly inevitable election as president.

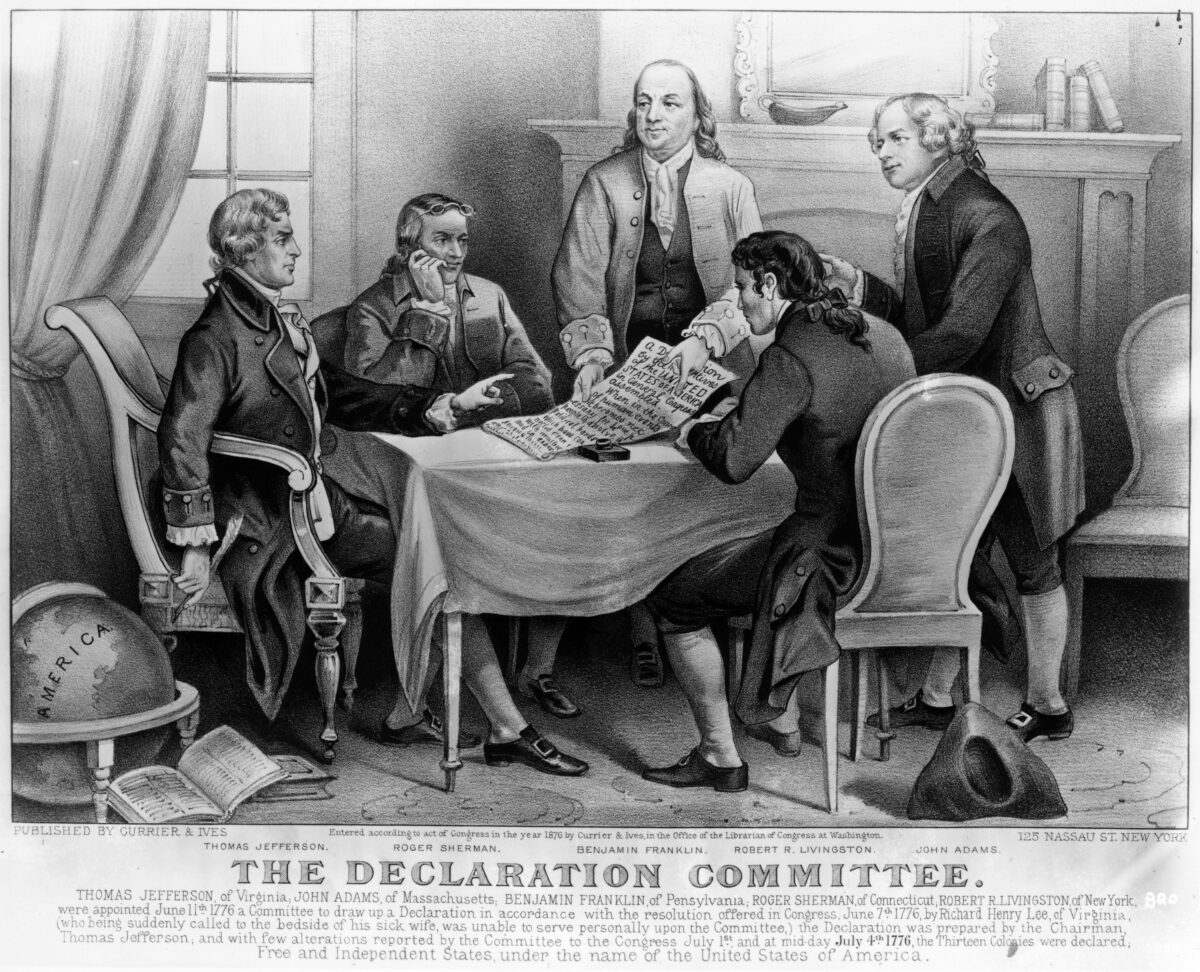

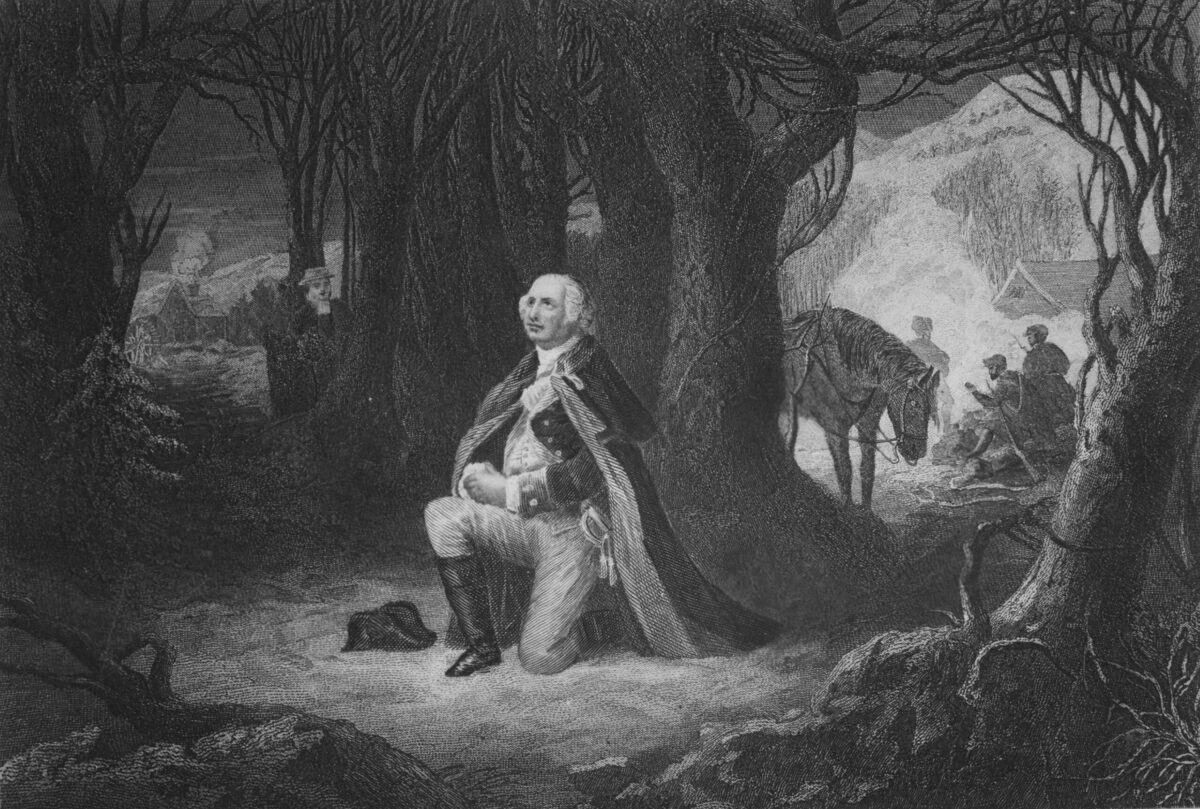

For eight years (between 1775 and 1783) and without pay, Washington had led the Continental Army against the British. The aristocratic Virginian might have gone on to leverage his impressive victory to become a “conquering general” and establish a personal dictatorship—an end conceivably within his grasp and even suggested by some in his circle.

Instead, George Washington very emphatically retired. Lest anyone should miss the point, Washington even delivered a public resignation address. His days of service were over, and beloved Mount Vernon was calling.

But now, he was being summoned into service once more. Two weeks after Washington had compared his feelings to those of a culprit on his way to execution, a dispatch arrived at Mount Vernon notifying the retired general of his presidential election. Two days after that, 57-year-old George Washington left Mount Vernon, penning the following in his diary:

About ten o’clock I bade adieu to Mount Vernon, to private life, and to domestic felicity; and with a mind oppressed with more anxious and painful sensations than I have words to express, set out for New York … with the best dispositions to render service to my country in obedience to its call, but with less hope of answering its expectations.

Perhaps no one in America was more familiar with the challenges of directing the new union than George Washington, who had played such a central role in its inception and evolution. As such, he was clearly under no illusion as to the challenges that awaited him. His acquiescence (for so it was) to the presidency was informed less by political ambition and more by solemn duty. There was no relishing of the prospect, no celebration on his part, no reveling in his political achievement. Being the sort of president people wanted—by unanimous vote of the Electoral College, no less!—seemed at the very least a daunting task, and probably an impossible one. He seems to have known this.

Bad Roads and White Robes

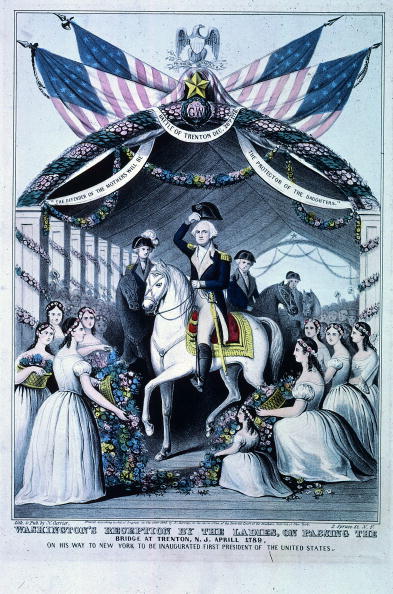

New York was to serve as the first temporary capital of the new United States of America, but great distance and bad roads meant that it was quite a journey to get there from Virginia. And if Washington was really weighed down by “expectations” at the moment of his departure, he was certainly more so as the journey progressed. Everywhere he went, crowds cheered his arrival, casting roses and wreaths along his path, or erecting triumphal arches for him to pass through. At Trenton, 13 girls—representing the 13 states—in white robes hailed him as “mighty Chief” in song, while Washington was made to ride beneath a 13-columned arch.

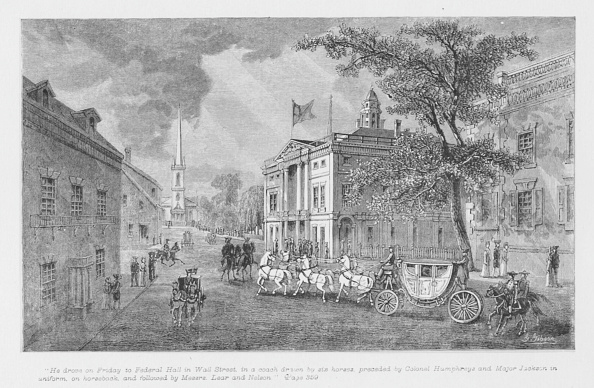

Finally reaching Elizabethtown, New Jersey, across the Hudson from New York City itself, Washington was greeted by an ostentatious barge manned by 13 white-uniformed captains. Upon this gaudy vessel, the president-elect was ferried across the river to where Wall Street met the water. New York Governor George Clinton awaited him there—atop a set of specially prepared steps with their sides draped in lavish cloth.

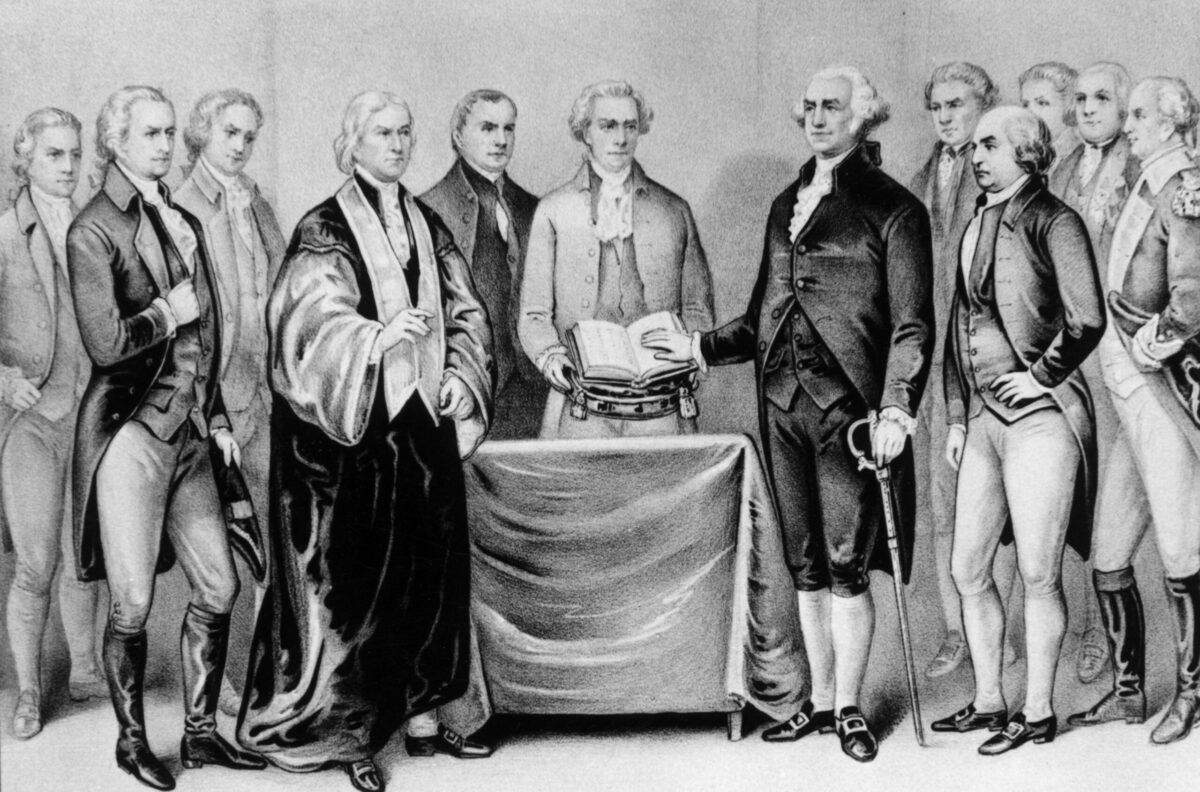

George Washington was sworn in on April 30, his oath of office administered on the balcony of Federal Hall, in front of a massive crowd gathered along Broad and Wall Streets and on balconies and housetops in every direction. All was hushed during the swearing in, after which the officiator exclaimed, “Long live George Washington, President of the United States!”

Thunderous applause echoed throughout the city as a 13-gun salute rang out from the harbor. As the ovation continued, an American flag was hoisted above George Washington himself.

Expectations, indeed.

Complainers

Of course, the hoped-for utopia to be ushered in by America’s greatest Founding Father never materialized. Even Washington himself had hoped that the new federation would, at the very least, avoid political factions. Instead, the real world offered its usual share of complication and contention—including a highly combative two-party system. By the time Washington left office, his once-invulnerable image had taken a hit among some contemporary people. Complainers picked at flaws, real or not. American newspapers attacked his perceived disloyalty to republicanism and his personal integrity. They attacked the lavish receptions (or “levees”) he hosted with his wife, his “aristocratic” airs, his alleged “monarchical” pretensions, his cold and aloof manner. Critics accused him of being unintelligent and susceptible to bad advice from his cabinet, of treacherously betraying France by proclaiming neutrality—and of betraying the American Revolution by not eagerly supporting the French one.

A whole series of letters (called the “Belisarius” letters, after their author’s pen name), addressed personally to Washington and published in opposition newspapers, lambasted the president on a wide range of counts: for cultivating “a distinction between the people and their Executive servants”; failing to stand up to (post-war) Britain; overseeing a costly war with the American Indians; maintaining a standing army in peacetime; and supporting internal taxation (then “denouncing” the people most affected by it), among other allegations.

Tempering Expectations

It may be that the aspersions cast in his direction were a primary reason George Washington decided to retire after just two terms. Indeed, an earlier draft of his Farewell Address actually included these words:

As some of the Gazettes of the United States have teemed with all the Invective that disappointment, ignorance of facts, and malicious falsehoods could invent, to misrepresent my politics and affections; to wound my reputation and feelings; and to weaken, if not entirely destroy the confidence you had been pleased to repose in me; it might be expected at the parting scene of my public life that I should take some notice of such virulent abuse. But, as heretofore, I shall pass them over in utter silence.

The impossible expectations placed upon the first president demonstrate, perhaps, the futility of investing in one individual the utopian hopes and dreams of an entire people. One of the original American lessons, at least as they pertain to the state, is that political saviors don’t exist; not even the vaunted George Washington could be one! He’d felt the weight of such expectations right from the beginning. That weight probably helped drive him out of the spotlight in the end.

When election cycles come around, perhaps our expectations should be tempered by Washington’s experience.

And when politicians talk like saviors, remember George Washington, too.

Dr. W. Kesler Jackson is a university professor of history. Known on YouTube as “The Nomadic Professor,” he offers online history courses featuring his signature on-location videos, filmed the world over, at NomadicProfessor.com