Stretching across 58 feet in Washington, D.C.’s Pershing Park is a bronze frieze that portrays “A Soldier’s Journey” through the demands and dangers of World War I. From left to right, 38 life-size human figures relate the experience of a single American soldier: his departure from home, the ordeal of battle and its aftermath, and his return.

The massive work, unveiled in an illumination ceremony on September 13, was created by Italian American sculptor Sabin Howard, whose lifelong quest is to revive figurative sculpture in the great tradition of the Renaissance. The fact that he has made his case in a large-scale piece commemorating World War I is something Howard finds deeply ironic.

“World War I marked the end of a philosophical thought process that the world is unified by a divine order. With the decimation of 22 million people, you move toward alienation and nihilism, the death of God and the beginning of the modern era,” Howard reflected. “That moment had a huge impact on art. The idea that the figurative is what art is all about was already starting to slide away. After World War I, the figure is no longer a part of the art world. The last moment that figure is paid attention is [during the] Art Deco [movement], and after that you move into abstract art.”

A hundred years later, Howard found himself commemorating in figurative sculpture those sacrifices made during the very event that led to the erasure of figurative art—ironic, indeed, yet somehow apt. “A Soldier’s Journey” is a powerful tribute to the Americans who fought in World War I, while its metaphysical reach “goes back to a previous age and speaks of our connection to the sacred,” Howard said. Its greatest potential: to spark what Howard calls “an American Renaissance revolution.”

Birth, Rebirth

Sabin Howard the man was born in 1963 in New York. But Sabin Howard the sculptor was born precisely at 4 p.m. on October 22, 1982.

“That was the moment I decided to become an artist. I was working in a cabinet-making shop, and I called my dad and told him. He said, ‘How long is this going to last?’ So far, it’s lasted 42 years.” Then 19, Howard did not know how to draw and was unfamiliar with the procedures of the art world. He called an art school to ask about requirements. “They said I needed a portfolio, but I didn’t know what a portfolio was,” he recalled.

All the same, Howard knew what he wanted. He persisted, earning degrees from the Philadelphia College of Art and the New York Academy of Art, and used what he learned in school to build upon what he had already experienced of the great masterpieces of Western art. Because his mother is Italian, he spent many formative years in Italy. There, “I was exposed to the great artists of the Renaissance, and I thought that’s what art is. I decided to make art like the Renaissance masters, especially Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo [da Vinci].” He chose sculpture because in the Renaissance, “everything—drawing, painting, everything—was guided by the three-dimensional energy of sculpture, which has such presence.”

The Aesthetic of the Figure

With his dedication to the Renaissance and figurative art came certain core values. “There are values that govern what art is,” Howard explained. “Art comes from experience, and experience is driven by the divine nature of how the universe is assembled. The artist takes something that stems from that sacred element and that shows something representative of our potential as human beings.”

Howard’s earliest works were sculptures of ancient deities such as Hermes and Aphrodite. In 2011 came the work Howard was convinced would bring him to the art world’s attention. “It was called ‘Apollo,’ a male nude that took 3,500 hours and two models. I thought I had made something comparable to the works of the Italian Renaissance.”

Howard’s “Apollo” was unveiled in a gallery in New York’s Chelsea district, “a huge space with huge glass windows floor-to-ceiling and light pouring out of the windows.” About 300 people showed up for the unveiling. And then, “Nothing. Nothing happened.”

It was a watershed moment in the artist’s life. He decided, “I had to do something different after the ‘Apollo’ because I was really down on myself. I’d worked so hard all those years, and nothing was breaking through.”

Change of Direction

In 2014 came a call from the commission of the National World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C., for proposals by architect-sculptor teams to create a park, incorporating a sculpture, that would commemorate the Americans who fought and died in World War I. In 2015, Howard, then 52, was chosen and teamed up with then-25-year-old architect-in-training Joseph Weishaar. Together, they conceived of a 58-foot-wide frieze that would be placed on a deck raised above a water feature.

Howard began work on the sculpture in January 2016, completing it eight and a half years later.

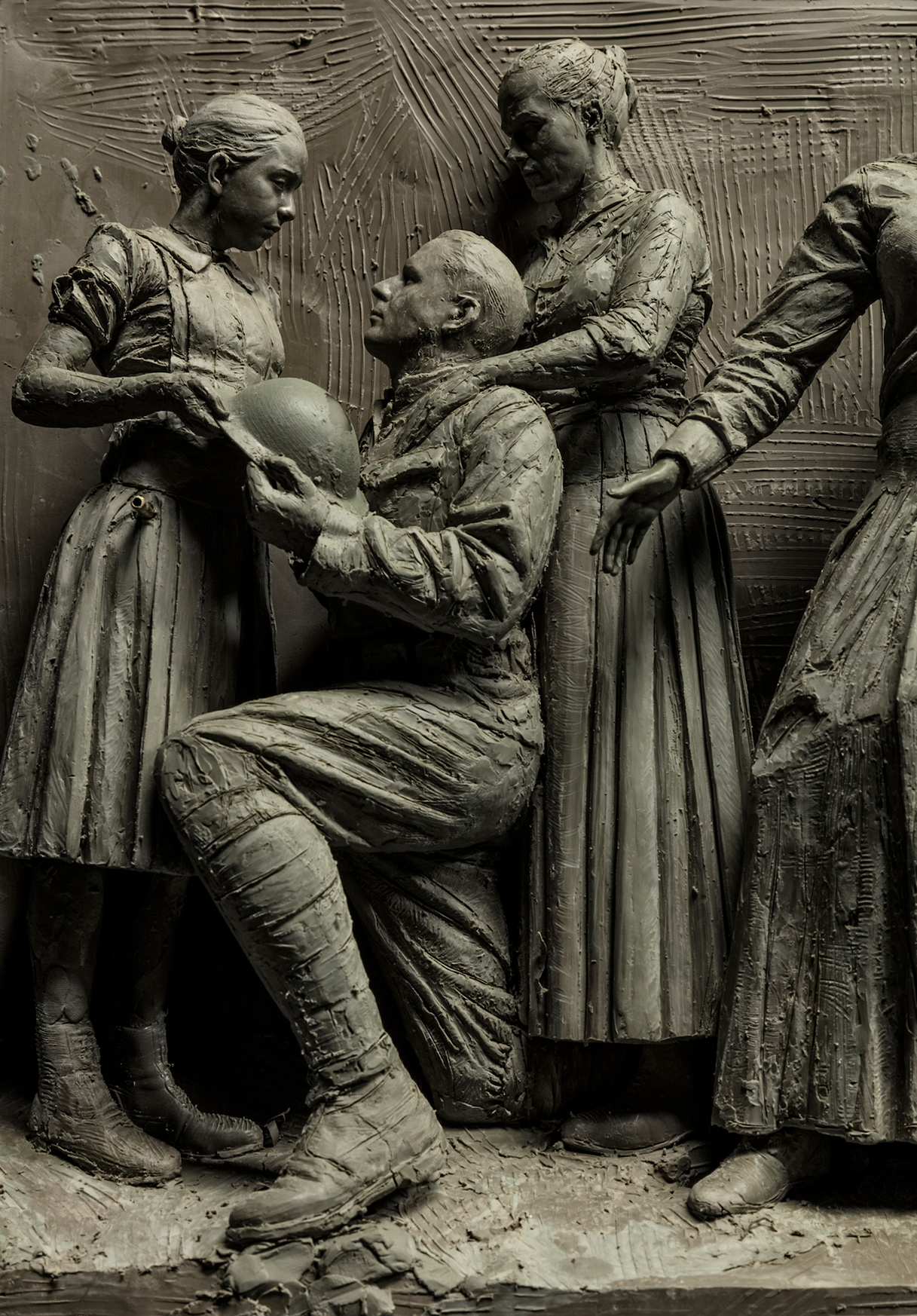

“Those years were dedicated to meetings with the commission and to 25 different iterations of the sculpture. Then came a 10-foot maquette and then another 5-foot version which became the final, green-lighted project. It was a battle,” he said.

One member of the commission suggested that Howard look at Henry Shrady’s bronze statue of Ulysses S. Grant, unveiled in 1924, located at the base of Capitol Hill. “I saw it and liked it and thought, ‘That’s a template I could follow,’” Howard recalled.

But not all figurative sculpture is alike, and Howard faced having to reshape his style. “I had to change from an esoteric, quiet classical style to one that is very vibrant and human and expressive and dramatic and kinetic. That’s a great challenge for an artist.”

Challenging in a different way were the “tortuous and difficult” meetings with the commission as the work progressed through its 25 iterations. “But in the end, it was worth it. It was almost like I had created something that tasted so good but so condensed, like French food. The flavor is very powerful and satiating, too,” he said.

Sculpture for Everyone

Howard called “A Soldier’s Journey” “a break from making sculpture for elites and governments.” His intention was for anyone to be able to connect with it. “An eighth grader with no interest in art will be fascinated by this movie-in-bronze that unfolds as you walk from left to right.”

At the start, we see a man saying goodbye to his wife and daughter as the daughter hands him his helmet. We move to the right and see him engaged in fierce combat, while men around him are killed, wounded, and gassed. We then see the solemn aftermath of battle, and the return home to wife and daughter.

As the action moves from left to right, the face of the protagonist changes to reflect the different races and ethnic groups that contributed to the war effort.

Howard’s wife, novelist Traci Slatton Howard, pointed out to him that the implied story of the sculpture parallels the “hero’s journey” story that is universal to the human experience.

Howard compares completing the enormous sculpture after nearly a decade of continuous work to “traveling at 90 miles an hour and then suddenly coming to a stop.” When he finished, he didn’t know what to do next, so he wrote a 750-page book about the experience.

He sees “A Soldier’s Journey” as the spear-tip of a potential shift from abstract to figurative sculpture and is not reticent to make his position clear: “Schools, art critics, galleries, and museums are arrogant and ignorant of what art is.”

To correct that, Howard believes we must re-connect with the divine that is inherent in human nature.

From Nov. Issue, Volume IV