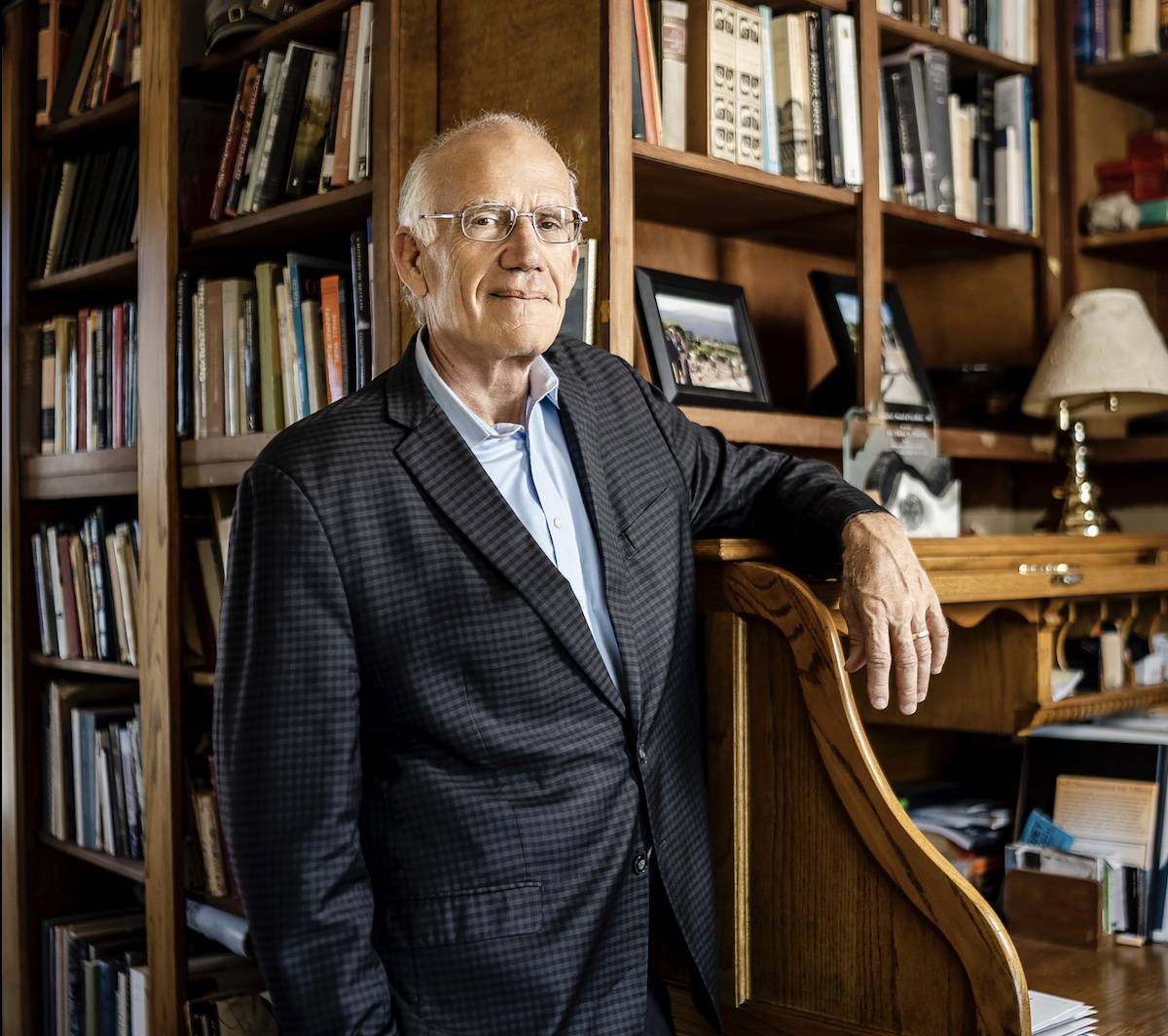

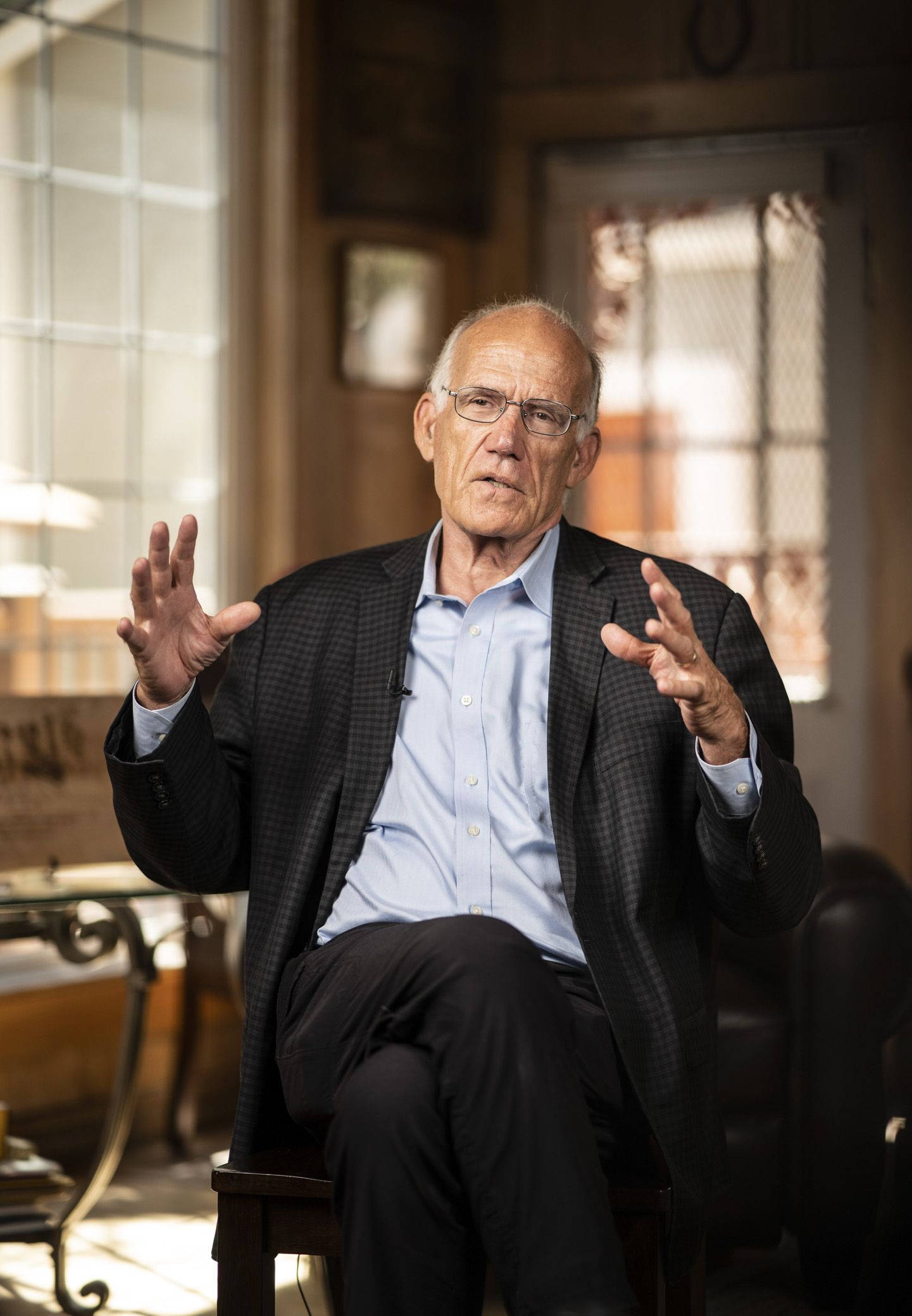

It’s nearly a 200-mile commute home for historian Victor Davis Hanson from the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where he travels once a week, to his quiet family farm in the fertile Central Valley of California.

As a classicist, he’s at ease with the ancient world but often brings a historian’s insightful perspective to current events. And he’s also a fifth-generation farmer.

His house, surrounded by almond orchards, holds many stories—from the generations who sacrificed all of their soul, sweat, and hard-earned money trying to save the farm, to later generations who decided this wasn’t the life for them and moved away with no intention of ever returning. Of the original 180 acres that were passed down through the years, only 42 remain—rented out to a farmer who owns 12,000 acres in the surrounding region. This is California, where agriculture has gone almost all corporate, leaving farming families with few choices: mainly to scale up vertically and jump into agribusiness, or to sell and move away.

The America where 40 acres per family was the norm is now long gone. But its personality, the strength of its communities, and its work ethic were all deeply shaped by family farming. In this conversation, Hanson talks about this important aspect of our nation’s heritage.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

American Essence: Looking back at America, and its early days as a nation, what was interesting to Europeans about what American farmers were doing?

Victor Davis Hanson: The history of Europe was always too many people, and too little land. When the American nation was founded, 95 percent of the people were homestead citizens, and they had their own land. They were completely independent and autonomous; they raised their own food. They were outspoken, and they were economically viable.

Observers who came from Europe, [for example] Alexis de Tocqueville, noticed that the American citizen was not a peasant. He was not indentured, he was not attached to a manor, or he wasn’t like an English subordinate. He wasn’t a Russian serf. He was an independent person because he had all of this land. And until the mid- or early 20th century, that was a peculiar characteristic of America—there was so much farmland, and there were so many people from all over the world that wanted to be independent farmers. That had been impossible in their own land.

And even today, when we have people from Asia, or India, or Mexico, it’s astounding how many of them want to buy land, because that was an unavailable, yet they have it deeply ingrained in their psyches: If you have land, you’re going to be protected, you’re independent, you can raise your own food.

American Essence: You mentioned a quote in an opinion article you penned in 2015. Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison in 1787, “I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries, as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become as corrupt as in Europe.” What is the connection between farming and preserving a virtuous society?

Mr. Hanson: That’s an old idea that farming serves two purposes. It’s not like agribusiness. It doesn’t just produce food, but it [also] produces citizens. The idea behind it goes back to Greece, if you read Xenophon’s “Oeconomicus” or Varro the Latin agronomist, the message that comes out of that is that farming requires your brain and your brawn. So you plan an orchard, but then you physically have to enact that, so if you’re a farmer who can only think, you’re not going to succeed in a pre-industrial society, but if you’re just a brute, you’ll make mistakes. So they felt that farming gave a person the perfect balance between the head and the body. And then it allows them to connect in a realistic fashion with nature. People in town … were either afraid of it or they romanticized it. But the farmer was a partner with nature. He knew that he had to kill bad bugs to produce wheat. But he also understood there were good bugs that ate the bad bugs. So he tried to find a balance.

In classical agronomy, the idea was that that process created a different type of citizen. In other modalities, people either didn’t own the land that they worked, or they were indentured—in other words, they had small plots, but they didn’t have a title to it. So if you give a man a title, and they own it, they improve it, and you have inheritance laws that allow them to pass it on, then you create an involved citizen. If the citizen is a serf, or peasant, or renter, then you cannot have a constitutional government because they’re restless, they’re envious, they’re angry, and they don’t improve the property when they rent something.

American Essence: Thomas Jefferson saw the yeoman farmer as key to the preservation of a good government. Yet over the centuries, that ideal has been displaced. A smaller and smaller chunk of the population farms the land, pushed out by agribusiness and government.

What then is there to conserve when we speak of conserving the farm and traditional food production?

Mr. Hanson: When the Founders ratified the Constitution, 95 percent of the constituency was farming. … By the end of the Depression, World War II, we’re down to 20 percent. It’s now down to 1 percent of the population is involved directly, or maybe 2 percent. So it’s maybe 4 or 5 million people out of 330 million.

The Founders were worried about a number of things. People wouldn’t know where their food came from. They wouldn’t have that experience of working physically, with nature, to grow something. They wouldn’t have a compound rather than just a house. The farmhouses, when I grew up, in the last vestiges of farming, were multi-generational.

So this house, I was told, in 1935, had 28 people living in it, and the other buildings around had another 30 during the Depression. When I grew up, this house was full: My grandparents lived here, they had a daughter who was crippled, we lived down the road, the kids free-ranged, cousins were here, neighbors dropped in. It was just booming. And that was what farmhouses were. So my grandmother had the Wednesday Walnut Club [consisting] of all the people who had walnut groves, and they tried to do self-improvement. Or they had the Eastern Star or they had the Masonic Lodge or the Elks Club. And when you look at them, they were all about self-improvement.

So it was the type of sinews and community that encouraged Little Leagues, hospitals, PTAs, community schools, but it’s wiped out now. All the houses around 40 acres, they’re wiped out. The person that I rent 42 acres to, he owns 12,000 acres. And the houses that he rents from used to be homesteads. They’re now usually inhabited by people from Mexico, many of them here illegally. There is an MS-13 group down here, there’s a gangbanger there. There’s prostitution there. There’s dogfighting. Because people are renting the home, and the land has been farmed by a corporation. So there’s no community. It’s rich and poor. And so that’s what Jefferson and other people were worried about. [Family farming] was a way of maintaining a middle class.

The $64,000 question is, can that ideology be transferred to a modern industrial society? So if you have an independent trucker—to take just one example—he owns his own rig, he’s a mechanic. He is an expert in refrigeration, and he’s responsible for his own load. He’s very different than a teamster that works for Walmart. In other words, he goes to a trucking dispatcher, and they say, “Mr. Smith, you’ve got to take 20 tons of steel to Dallas,” and he figures out the route, he works on his own truck, and he does it. And that creates an independent-minded person. And you can see that when parents run into a school board and say, “You can’t teach my child this,” or “We’re not going to take this.” Often, they tend to be small business people. You have to have people like that in our society. You can’t have everybody working for the government or corporation.

American Essence: How can we maintain the values without that farming family backbone?

Mr. Hanson: It’s very hard because their values are based on shame in traditional societies, and we have transmogrified that into guilt. So if I was in this house 60 years ago, and my grandmother said to me, “You said the word ‘darn.’” She just wouldn’t have said, “You said the word ‘darn.’” She said, “Are you gonna go out there and say that word in front of everybody? What are they gonna think of us? They’re gonna think we taught you that. You don’t say that or you’re going to shame the entire family.” Whereas today, it’s maybe at most private guilt, “Oh, I feel so bad I said it,” but there’s no mechanism to enforce behavior.

I remember my grandfather would say, “Now you’re driving to high school. So I know what you boys do. You all go have a beer on Friday night, but you’re under 21. You want your parents to wake up on Saturday morning and it [a newspaper headline] says, ‘Hanson boy caught with Coors beer in his car’? They will do that, and then what are we going to do?” So that was the emphasis. That’s what the modern therapeutic society rebelled against and said, “That’s judgmental,” but they didn’t replace it with anything other than, “Oh, it wasn’t my fault,” or “I had a bad childhood,” or “I was offended,” or “It was unfair,” or “They did this to me because of my race or sex or gender.” That was a very different method of maintaining a more collective morality.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.