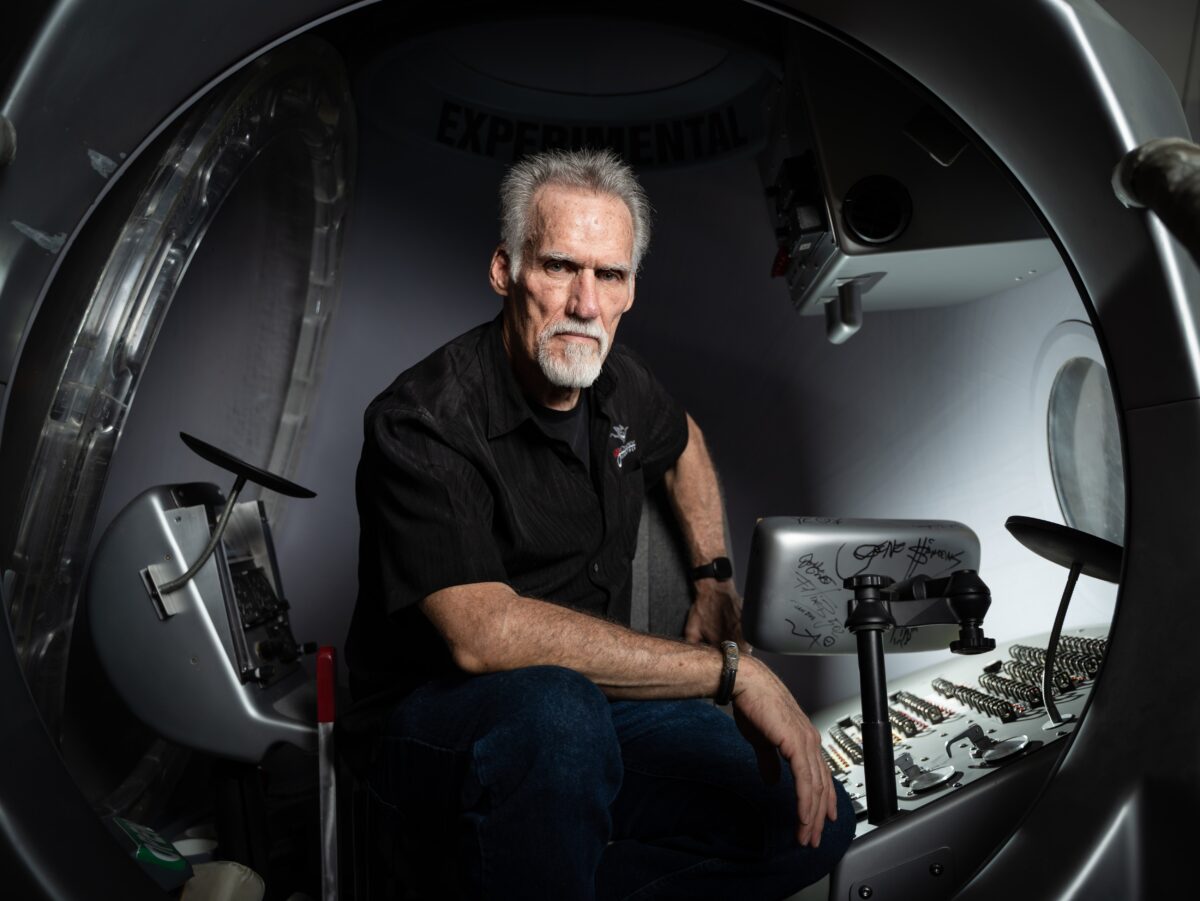

What does it take to forgive someone who tried to kill you?

To Virginia Prodan, it was simple. Being a woman of Christian faith, she lived her life by the principles expounded in the Bible. What she wasn’t prepared for was how the assassin sent to kill her reacted to her plea. Not only did he put down his gun, but he ended up changing his entire course of life afterward.

Prodan met her killer’s eyes and asked, “Have you ever asked yourself, ‘Why do I exist?’ or ‘Why am I here?’ or ‘What is the meaning of my life?’ I once asked myself those questions,” as she recounts in her memoir, “Saving My Assassin.”

He slid the gun back into the holster. Prodan proceeded to describe God’s capacity to forgive all who have sinned. The man softened, and eventually inquired about the faith that gave her the power to face him so bravely. “I will come to your church as a secret brother in Christ. I will worship your powerful God,” Prodan recalls him saying.

Prodan’s supposed offense, which led to her inclusion on the hit list of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, was defending Christians who were not allowed to exercise their freedom of belief. As a Romanian lawyer, she took on dozens of cases involving Christians who faced persecution for their faith during Ceausescu’s regime of the 1970s and 1980s. Some had their work licenses revoked or were charged with crimes because they had a Bible in their possession. Others turned to Prodan when the land that churches sat on was in danger of getting confiscated by authorities. During a time when Ceausescu only allowed citizens to worship himself, Prodan’s courageous defense of citizens with faith brought the attention of international reporters and U.S. officials monitoring the situation in Romania. Her court cases showed the world that religious freedom was absent in Romania. It angered the dictator so much that he hired a hitman to finish her.

Years later, after Prodan made a daring escape to freedom in America, she would meet him again in the most unexpected of circumstances. “We are not enemies to each other,” she said in a recent interview. “God changed my assassin; God can change everyone. … God changed Romania through me.”

Seeking the Truth

Prodan grew up in an abusive household that did not cherish her. Prodan’s book describes a childhood in which her mother constantly reminded her that her freckles and red hair meant that she did not belong. She was often left at home to do chores while the rest of her family was gone on vacation. If she did not do them correctly, she would be punished with beatings. “As a child, in order to avoid punishment—for every single situation, I learned to find solutions,” Prodan said. She reflects that this was perhaps her training ground to learn how to rise above the circumstances and gain the resolve to overcome anything. “In life, sometimes we don’t understand why we go through tough times and why we have to endure those things. But those hard times will prepare us for something really, really wonderful that otherwise we will not be prepared for,” she said.

Books were her escape from reality. She excelled at school. After witnessing how the Romanian regime persecuted her uncle and her next door neighbor, Prodan became determined to study law. Her uncle was forcibly taken to the psychiatric hospital three times for daring to speak up against the regime—though the family never spoke about what exactly he did that made him a target for the Romanian Communist Party. “A fire started to build in me to find and understand the truth and understand why adults will know the truth but be too fearful to speak the truth, and also how to be strong and courageous and speak the truth. … That became my mission in life,” Prodan said.

Discovering Her Mission

Prodan applied successfully to law school and passed the bar exam for working in Bucharest, the capital of Romania. Her first solo case was a pro bono case to defend a university student accused of burning his Communist Party ID card. He faced a 10-year prison sentence. Prodan found out that her client was coerced into confessing to committing the offense. She persuaded the client and his parents to testify and admit that he was forced to confess. In the end, the judge sentenced him to two years of community service. His family continued to be harassed and interrogated by police after the trial. His father suffered a heart attack during an intense interrogation session and died. Soon after, the client hanged himself, and the rest of the family disappeared out of sight. Prodan felt lost.

One day, a church goer asked her to represent him. The communist regime had confiscated his family’s land. While assisting him with the process to get the property back, Prodan was introduced to Christianity. The regime considered the Bible’s teachings as running counter to Communist Party doctrine, but in an attempt to appear like the country respects freedom of belief, the government still allowed churches to operate. However, Christians were routinely persecuted and could be arrested for having the Bible in their possession. Prodan soon found herself defending church organizations and believers in court. Her courageous defense, accusing Ceausescu of human rights violations, garnered the attention of observers in the American embassy and international media. “People all over the world found out that a young attorney in Romania, a woman under 5 feet tall, 82 pounds, is taking the dictator to court,” she said.

Danger Ahead

Prodan soon found herself directly targeted by Ceausescu’s government. One day, as she was leaving her office and getting ready to go to the courthouse, a homeless man followed her and pushed her into oncoming traffic. She was constantly followed by Securitate, or secret police. One day, several officers forced her into an unmarked black car and took her to the Securitate headquarters. They hit her and threatened to put her in prison for life. Though they released her that evening, the scare tactics continued. Officers would ransack her home and her office. She faced more interrogations in which she was beaten by Securitate officers. On some occasions, “they will come inside of my home, eat the food, and leave the dirty dishes, or move the furniture around, because they wanted to play a psychological game,” Prodan recalled.

There were days when she would let the tears run down her face. But she refused to cower before authoritarianism. She believed that it was her mission to defend religious believers. “You have to just trust God, when you know that he is the one who gave you that mission … if you look back, that he will give you tools and open doors for you to accomplish that mission.” She recalled moments when she would be searching for provisions in the arcane Romanian code of law that, at least on paper, guaranteed a Romanian citizen’s freedom of belief. She would flip open the book—and it would miraculously land on the page that contained the information she needed.

Assassination Attempt, Escape to Freedom

One day, after Securitate officers slammed her head against the desk repeatedly during an interrogation and threatened to harm her children, she returned to her office, shaken but pretending as if all was OK. Her legal assistant told her a man was waiting for her to discuss a case. When the man entered her office and closed the door, he drew a gun. “I believed that I would be dead the next moment,” Prodan recalled. “My knees were shaking. I heard my stomach. I heard my heart in my ears. I was shaking. I even thought that my kids will live without a mother. But in all this, I heard also the whisper of God saying, ‘Share the gospel,’” she said.

Prodan describes the next few moments in her book, as she calmly spoke to him. “‘You are here because God put you here, and he has put you to a test. Will you abide in God or in the will of a man—your ultimate boss, President Ceausescu, who requires you to worship him? God has given you free will to choose.’”

Moved by her words, the assassin quietly listened as Prodan recited passages from the Bible about the power of forgiveness. By the end, he told Prodan that he would start to explore Christianity, and walked away.

But this was not the end. The next morning, two armed police officers blocked Prodan and her daughters as they left their house. They informed her she was being placed under house arrest. For four weeks, Prodan was stuck inside, with food supplies dwindling. When all hope seemed to be lost, the American ambassador’s wife managed to sneak to Prodan’s house, letting her know that the American embassy knew of her situation and was finding ways to help her.

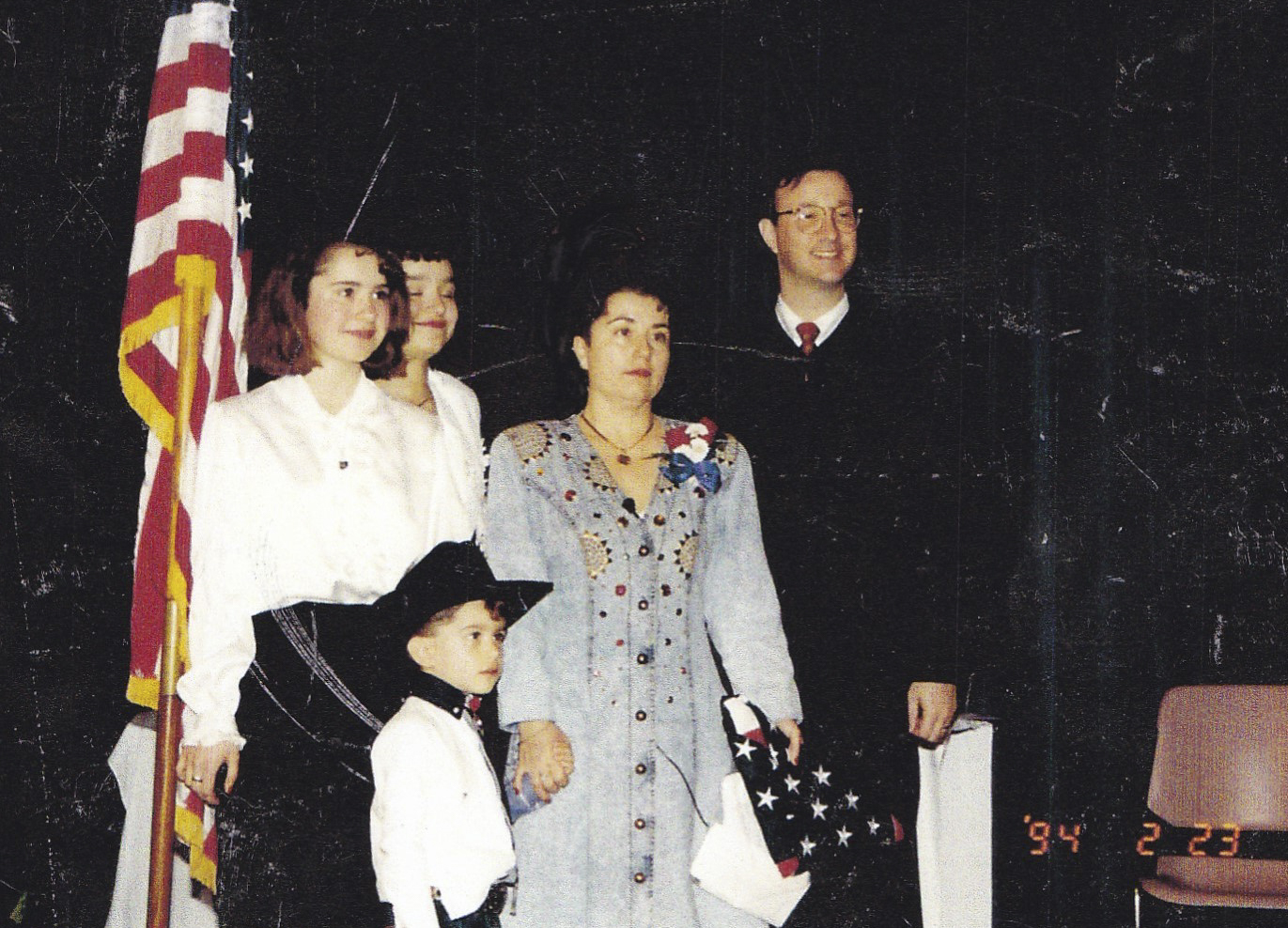

U.S. President Ronald Reagan authorized Prodan and her family to move to America as political refugees. Prodan was released from house arrest and allowed to go to the local passport office to get her paperwork. After transiting through Rome, Prodan and her family arrived in Dallas, Texas, in fall 1988.

Life in America

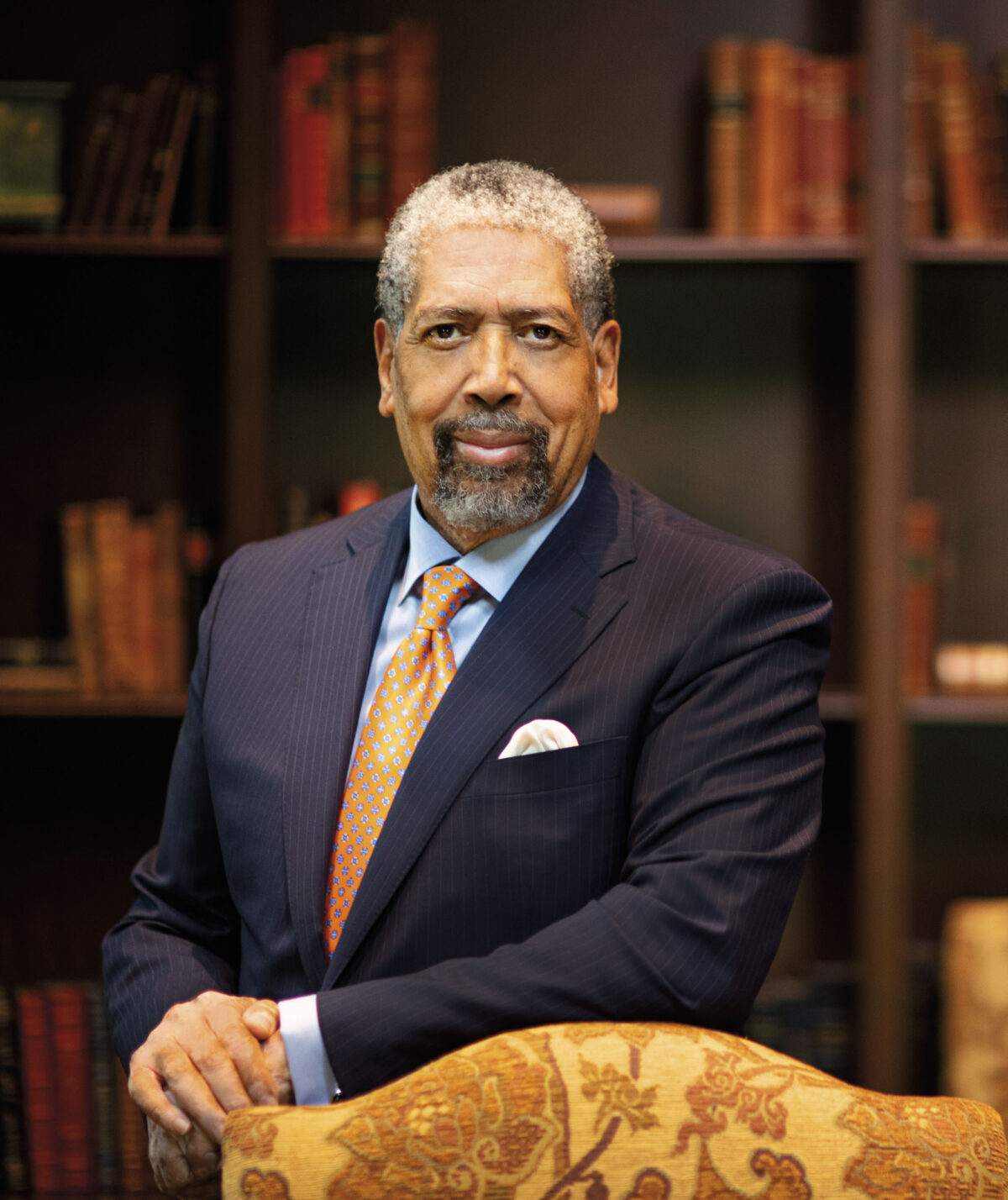

Upon settling in Dallas, Prodan went back to school to receive a law degree from Southern Methodist University’s law school, then opened her own practice. To this day, she continues to take on clients who feel their freedom of belief and freedom of expression have been infringed upon. She feels blessed to be in America. “American people are like no one else. They will open their hearts, they will open their houses [to you]. They encouraged me to go on and rebuild my life,” she said.

One day in 2010, she received an unexpected visit. A man came to her office and explained that the church where his son was pastor had encountered some legal trouble while seeking to construct a building. Suddenly, he asked, “Virginia, do you remember me?”

It was the assassin. After stepping out of Prodan’s office in the 1980s, he’d studied theology and became a pastor in Bucharest following the collapse of the Romanian communist regime. Now, he pulled out his phone to show Prodan a photo of his newborn granddaughter, who was named Virginia in Prodan’s honor. It was an emotional reunion. Michael—the name he adopted in America—was eager to share with Prodan the impact that faith had in his life. They caught up over lunch, but when Prodan asked to keep in touch with him, he explained that he was worried about repercussions in Romania. There was a growing wave of people calling for former participants in Ceausescu’s regime to be brought to justice. “Lots of Romanians asked the government to punish those people,” Prodan recalled Michael explaining to her. He told her that “it’s better for me not to know about his whereabouts. Because the government might come against [him].”

Have No Fear

Throughout the years, Prodan has received anonymous letters and emails about former Securitate officers being jailed in Romania. She also receives a Christmas card from time to time, with the name “Michael” signed. She suspects these were all from her former assassin, quietly signaling to her.

Prodan said her experience not only allowed her to see how faith can transform even a cold-blooded assassin, but that there is nothing to fear in life. “Fear will just make you a slave. Fear will destroy your enthusiasm. But in order to conquer that fear, you have to confront that fear,” she said. She frequently recounts her story as part of motivational speaking engagements.

More importantly, she said, our actions are greater than ourselves—just like how she unexpectedly helped to change the course of Romania’s future. “My life and your life, it’s not only for us. What we do, what we accomplish, what we influence—sometimes we know, sometimes we don’t know. But we’ll reach beyond our imagination, [for] people, countries, generations to come,” she said.

From February Issue, Volume 3