In the big cities and small towns across America, young and old alike daydream of cruising the curvaceous coast of California on charismatic Highway 1. There are breathtaking stretches etched between sheer cliffs and surging sea wind, from crystalline coves to redwood groves and from Los Angeles city lights to San Francisco heights.

Along the highway, you can refuel and revel in the dozens of coastal towns, iconic and historic edifices, parks, and beaches, all while gaining insights into the exciting driving experience.

The longest state route in California, Highway 1 extends 650 miles from San Juan Capistrano in Orange County to Leggett in Mendocino County. It’s time to pull down your visor; you’re facing the sun’s glare, with a steep drop just beyond your passenger’s right elbow. Known also as the Pacific Coast Highway, it doesn’t constantly cradle the shoreline, and segments range from rural road to urban thoroughfare.

In 1937, the highway was completed with the blasting of rock faces and erecting of aerial bridges spanning cavernous chasms. A tenuous, narrow strip along the coastline was created, with stretches of cliff-clinging, hairpin-turning roads. Whether you are cruising the tight track in a humdrum Hyundai or a snazzy Mustang convertible with the wind in your hair and the sounds of the Beach Boys’ “California Saga” in your ears, this drive uncorks clutch-the-edge-of-your-seat excitement.

You never know what’s over the next rise or around the next bend. It might be mountains that plunge nearly perpendicularly into the ocean, surf and wind that pound the rocky shore and contort the cypress trees into otherworldly shapes, or a sheltered cove harboring a tranquil sea painted in shades of turquoise and sapphire.

Beach Towns

Heading northwest, the dry inland heat gives way to the cool sea air, as the tangle of metroplex traffic loosens, and you enter the embrace of the Pacific Ocean. The longest and most accessible sandy beaches along Highway 1 are found on the 95-mile expanse from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara.

Malibu has achieved mythical status among California beach towns for its sun-kissed Hollywood stars, who are drawn by the celestial-high real estate, and its perfect curl waves that attract walk-on-water surfers. Even for Malibu surfing mortals, there’s a rush of adrenaline when a breaker curls over your head, and you can see the light of day as you pass through the crest of a wave.

The Santa Ynez Mountains are a statuesque backdrop to the Santa Barbara coast, referred to as the American Riviera. The exquisite Mission Santa Barbara, known as “Queen of the Missions,” inspired the colonial style of the city. Few structures define the Spanish heritage of our nation like the 21 California missions established during the 18th and early 19th centuries, according to the National Park Service.

After its longest inland foray, Highway 1 cuts back to the coast close to Morro Bay. The seaside town sits along a natural estuary inhabited by blue herons. The bay is notable for a solitary, 576-foot-high volcanic rock that was once a prominent landmark for mariners. On the embarcadero, sleek seals and shaggy dogs raise a ruckus barking at each other. Fishermen unload and weigh their catch; gulls squawk and flock to tossed salmon scraps.

A Hilltop Castle and Big Sur

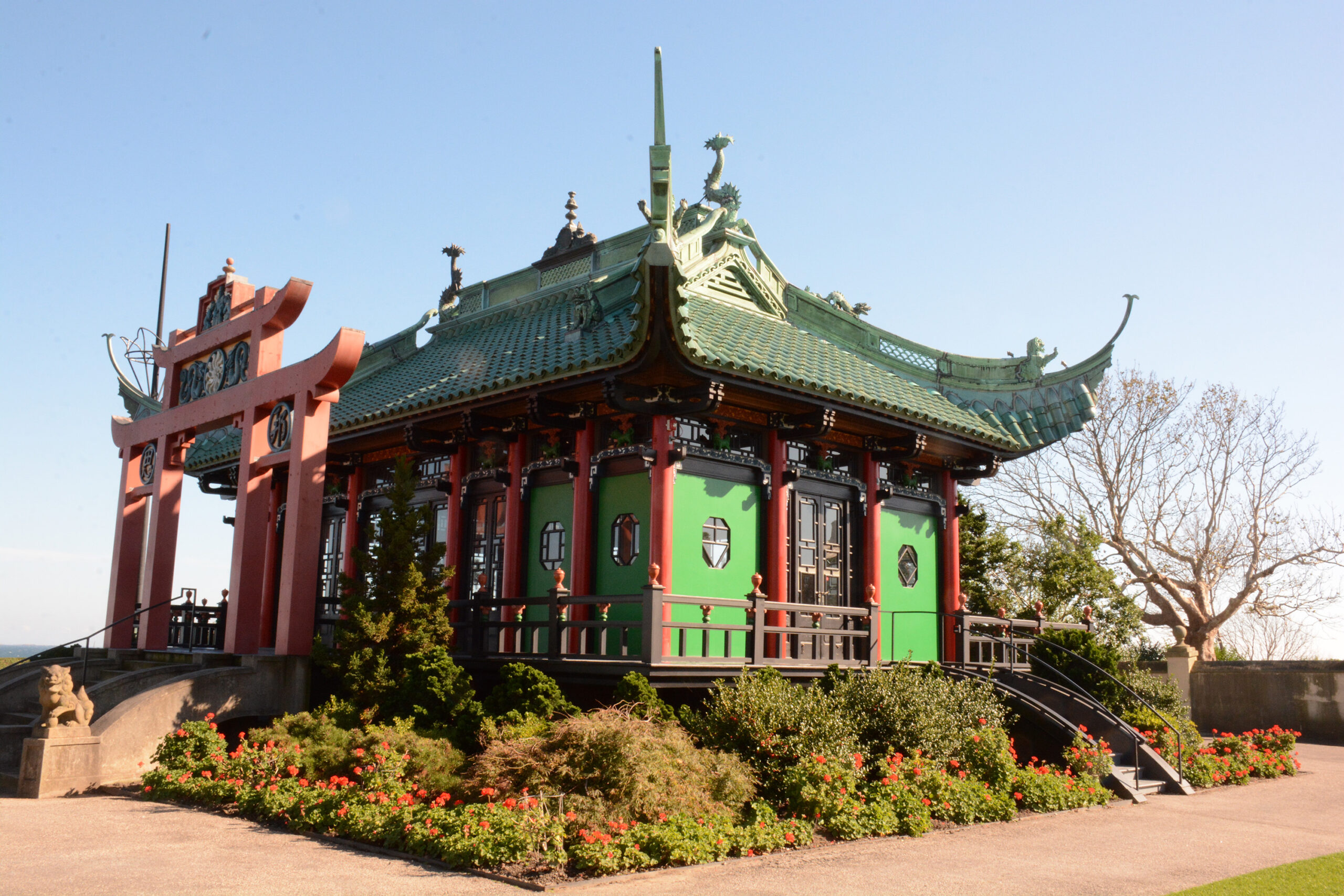

The central coast’s diminutive San Simeon soon comes into sight with Hearst Castle standing sentry. Newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst’s fabled hilltop castle began construction in 1919 and was never completed. A magnet for Hollywood celebrities during the 1920s and 1930s, today the site attracts about 700,000 annual visitors, who are drawn to the opulent extravagance of the extraordinary estate. They marvel at the ornately decorated and furnished 124-room mansion and the three guesthouses reigning over a crown jewel coastline.

Nearly in the shadow of the castle lies the under-the-radar Piedras Blancas rookery. More than 25,000 elephant seals pile up seasonally like bloated bratwursts on a narrow crescent of rocky beach. The behemoth bulls inflate their trunk-like snouts to make a roaring bellow. The portly pinnipeds ponderously waddle in and out of the water, crowd together to sunbathe, throw sand over themselves, and erupt into brawls.

The 90 miles from San Simeon to Carmel bring you to the Big Sur region, with a wild and rugged coast and rough-and-tumble mountains. Encompassing five state parks, a national forest, and a wilderness area, Big Sur is a milieu of meadows and hillsides awash with brilliantly turned-out wildflowers and canyons crowned with magnificent redwood cathedrals. California condors, with a wingspan of more than 9 feet, soar in bright cloudless sky or amid fingers of fog.

Delightful Scenes

Carmel is an enchanting and whimsical seaside enclave of fairy-tale cottages, posh art galleries, and chic boutiques that captivate the creative set. An eminent departure is the most faithfully restored of the California missions, the Carmel Mission Basilica Museum. Dating to 1770, it houses an impressive collection of original paintings and relics, most notably “Our Lady Of Bethlehem,” a statue that migrated with the missions’ founder Father Junípero Serra to Carmel.

20th-century writer John Steinbeck immortalized neighboring Monterey in his novel “Cannery Row.” The gentrified waterfront would be unrecognizable to the writer who eight decades ago described its historical pedigree as “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream.” The cannery was once filled with the sounds of men whistling and hollering, rivers of silvery fish pouring out of boats, and the clangor from titanic turbine pumps. Then, the sardines disappeared from the bay in the early 1950s. Over time, all fell silent. The last operating cannery was converted into the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

It’s a short shoreline stroll to the Fisherman’s Wharf, which once served as a fish market and now is a tourist hub. Affable, 80-year-old Captain Chris Arcoleo owns and operates Chris’ Whale Watching. There’s no better than Captain Nick Lemon, who has worked for him for 62 years, when it comes to spotting whales. “This is the Serengeti [national park in Africa] out of all the oceans that I have sailed throughout the world,” seaman Keith Stenler told boat passengers gawking at a congregation of two-dozen humongous humpback whales.

On the northern edge of Monterey Bay, about an hour’s drive, is Santa Cruz, celebrated for its surfing culture and laid-back lifestyle. Surfers can be seen pedaling their bicycles through town carrying their boards. The nostalgic boardwalk contains the West Coast’s last seaside amusement park. The fun-for-all atmosphere is punctuated by squeals from nervous Nellies riding the Giant Dipper, a century-old wooden roller coaster. For the faint of heart, the 1911 Looff Carousel still spins a magical spell with 73 hand-carved horses, an original band organ, and rings to toss into the clown’s mouth as you whirl by.

The highway crosses San Francisco’s graceful suspension bridge—the engineering marvel fancifully described as a “giant harp hung in the Western sky” by the late USC librarian Kevin Starr in his book “Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America’s Greatest Bridge.” The bridge lives in the national imagination as a symbol of American enterprise and as the gateway to the Pacific. Upon its completion in 1937, chief engineer Joseph Strauss heralded the triumph with his poem “The Mighty Task is Done.” A partial stanza reads:

The Bridge looms mountain high;

Its titan piers grip ocean floor,

Its great steel arms link shore to shore,

Its towers pierce the sky.

Fewer Souls

Once beyond the Bay Area, the road becomes less crowded, as many tourists opt for the convenient start and end points of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

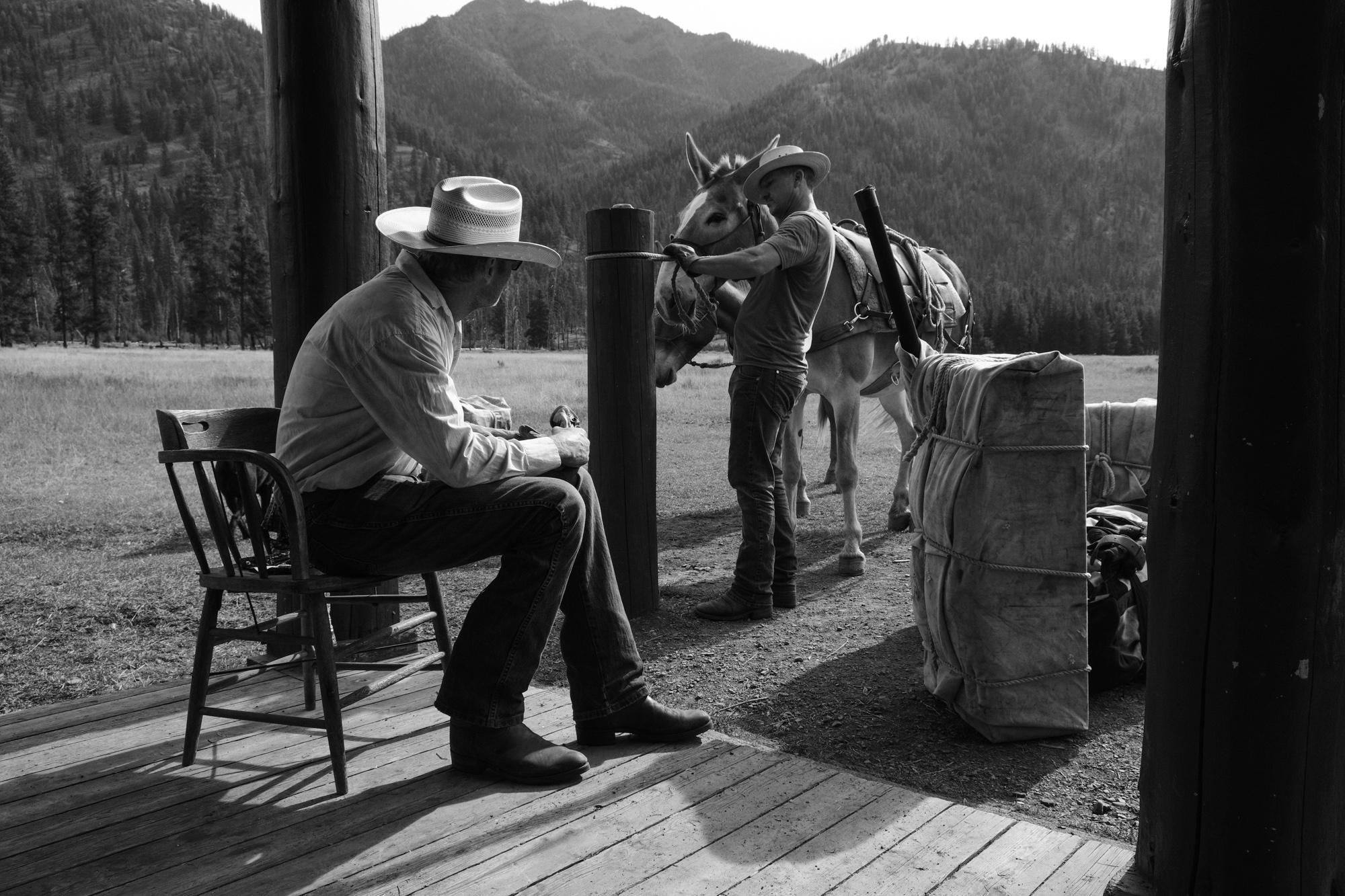

This northern portion of Highway 1 is synonymous with splendor and serenity. From San Francisco, it’s about two hours to the harbor-hugging hamlet of Bodega Bay. Nearby Chanslor Stables offers guided trail rides in a peaceful and picturesque pastoral setting. The 40 quarter horses on the 400-acre ranch are lovingly trained rescues, which saddle-savvy riders can scamper down the ocean strand with. “The most amazing experience I’ve had riding,” said 29-year-old senior wrangler Taylor Piercy, “was racing down the beach with a deer. When you’re on a horse, you’re just extra fun to a deer.”

Highway 1 treads the periphery for the next 137 miles overlooking offshore sea stacks and rock arches: sandy beaches separated by surf-swept headlands. The residents are romantics: lovers of solitude and the wild. They carve out a living in precariously perched, cliffside settlements with fewer souls than seals.

Here, you can make your way down to the serrated shore and scramble out onto a ragged reef. Once you peer into the tide pools at the underwater wonders, you’ll see vibrantly colored sea anemones with flowing tentacles that emulate petals of tranquil flowers, clustered among rocks covered with white barnacles that resemble miniature volcanoes. An ochre starfish may stretch its purple arms. When you reach into the brine, you may find a two-toned spiral shell shaped like a turban; it stands up on crab legs and skitters away.

The Russians Aren’t Coming

By the time the morning fog lifts from the hillsides at Fort Ross State Historic Park, the two-century-old wood-burning oven is loaded with hearty loaves of bread. Little boys clamber onto the cannons. Dancers hold hands as they circle the parade ground, singing Russian folk songs. The women and girls wear long, brightly patterned dresses, with strands of amber beads around their necks, their hair swept under colorful scarves—festive attire for a weekend gathering. The men and boys are dressed in simple white tunics, belted at the waist.

Set high on a natural escarpment commanding a stunning view of the sweeping seascape, Fort Ross was established in 1812 as Russia’s only colony in the contiguous United States. The only original building that remains is the one-story family dwelling belonging to the enterprise’s last manager. The outpost was abandoned due to lack of commercial success in 1841.

After navigating the curves and crannies of the coastline beyond the fort for an hour, a 2-mile spur road threads the needle of land, leading to the Point Arena Lighthouse, anchored on the cusp of a crag 50 feet above thunderous breakers. Visitors can climb the spiral staircase of the state’s tallest lighthouse. It was built two years after the 1906 Great Earthquake destroyed the initial structure that had guided mariners away from perilous waters since 1870. Station keepers and their families have endured battering winds, slashing rain, and the low rumbles of the foghorn for more than a century.

Fragrances

Thirty-five miles farther, Highway 1 appears to lose its bearing. The quaint maritime village of Mendocino is more reminiscent of Cape Cod than California. Prim saltbox cottages are framed by red roses and white picket fences. An artisan assortment of wind chimes tinkles in the sea-scented breeze. Cozy B&Bs welcome you to curl up by the fire; fine restaurants serve freshly caught seafood and local organic wines.

Meanwhile, the Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens, terraced on lofty bluffs, first greet visitors with waltzing wildflowers and storm-twisted conifers. Here, you can explore the tableau of manicured formal gardens, dense pine forest, and fern-covered canyons; and delight in the floral displays of rhododendrons as big as wedding bouquets, dahlias in Popsicle colors, and magnolias with the fragrance of orange blossoms.

Almost within arm’s reach are the brawny shoulders of the biggest and most vigorous town on Highway 1 north of San Francisco: Fort Bragg. With a population of 7,000, the town operates a commercial fishing harbor tucked into forested hills at the mouth of the Noyo River. A block off Main Street stands the depot for the vintage excursion Skunk Train, dating back to 1885, when it first transported loggers and freight. Foul exhaust fumes evoked the odious nickname the company has since shrewdly embraced. “Disneyland has Mickey Mouse, we have Mr. Skunk,” general manager Stathi Pappas said jovially about their mascot.

Driving in a Ladybug-Like Pattern

The oft-fog-blanketed and brooding northernmost 70 miles of the highway are little traveled: motorists typically cut over at Fort Bragg to U.S. 101. The road bends inland at the halfway point just above the squall-scoured palisades of rustic Rockport.

The dizzying drive delivers the most posted 10-miles-per-hour twists. It’s mechanical poetry interweaving the countless curves in a syncopation of acceleration and braking. You coil around ridge after ridge. The road curls in on itself and rises, only to drop again. You make your way up, mimicking a ladybug trying to cross a rose in bloom.

Your last descent is near the route’s end at the erstwhile logging camp Leggett, known for the drive-through “Chandelier Tree.” The towering redwoods in this area create a spreading canopy of arching branches over the storied highway. Five-fingered ferns and delicately flowering sorrel form a lush understory along rippling creeks, with dense thickets growing over fallen, Goliath-like logs. “They are not like any trees we know,” Steinbeck reflected in “Travels with Charley,” his travelogue documenting a road trip he made in 1960. “They are ambassadors from another time.”

For 650 miles, the thin ribbon of highway stretches ahead to the horizon, capturing your attention and unleashing your imagination. It reveals the natural splendor and a timeless spirit representing land and sea’s dramatic embrace. The route can inspire a dreamer’s poetic musing and an adventurer’s intrepid quest. The Highway 1 road trip is a rite of passage, and it reminds us that it’s as much about the journey as about the destination.

From April Issue, Volume 3