Fran Solomon’s 20 years of working in bereavement care began with an intense personal experience. “My father died in 1998,” she said. “His death was the first of a significant person in my life. I did what I think many people do. I grieved through the funeral, and then I had to get ready to return to work on Monday. “So I put my grief into a box, tied a pretty bow on it, and stuck it on a shelf. I thought I was going to get over it, move on, and with time, forget.

“Fast forward to 2002, my daughter was born. Somehow this beautiful life that had entered mine was accompanied by profound sadness. A friend sat with me and listened to all the reasons for my sorrow. Then there it was. The last thing I said encompassed all my grief,” Solomon said. “I was grieving that my father wasn’t here to see the one thing he had wanted more than anything —to have a granddaughter. Until that moment, I had no idea that the loss of my dad had had such a profound impact on me. It had resurfaced now many years later, as I welcomed my daughter.”

It ended up impacting Solomon’s own relationships going forward. “Because of my friend’s willingness to sit and listen, I was given an invaluable gift. I was able to understand the association between my sadness around the birth of my daughter and my father’s absence. Had that not happened, my relationship with my daughter could have become a resentful one, resulting from my having displaced my emotions. Through that experience, I came to understand the importance of bereavement care for support, understanding, and appreciation for what grief really is.”

Solomon founded HealGrief.org, a non-profit website that provides the tools, resources, and information to guide one’s journey after a death, through grief and into a healthy post-bereavement equilibrium. It also provides a place to celebrate the lives of loved ones, including pets.

The site provides these tools through offerings like a podcast archive, featuring interviews with a wide array of people who have survived the grief process themselves. The podcast, Let’s Talk Death, can be accessed as a printed transcript, as audio only, or viewed. Central to its mission is removing the cultural taboo that has surrounded death. A virtual support network connects people who are grieving with others who have lost loved ones too. These connections help to dilute the feelings of isolation often associated with grief.

Philanthropy has been a long-term commitment for Solomon. She has been a member of the Cedars Sinai Medical Center Board of Governors for some 20 years. Simultaneously, for a decade, she served as a member of the Board of Directors, as well as the Chair for Our House Grief Support Center, a community-based agency located in Los Angeles.

Now a certified grief-recovery specialist, Solomon lives in LA with her husband, Rick, and their three children, Matthew, Alex, and Lianna. Solomon’s husband serves on the HealGrief.org Board of Directors. He has long supported her work, she said, because he’s realized how much it has enriched her life and the life of their family.

During her work with Our House, Solomon’s focus began to expand beyond community boundaries. She realized that grief is universal. She perceived the need for a place where people across the world could come to celebrate the lives of those they love. She realized that this place also would need to provide resources to help those who are struggling with grief to recover.

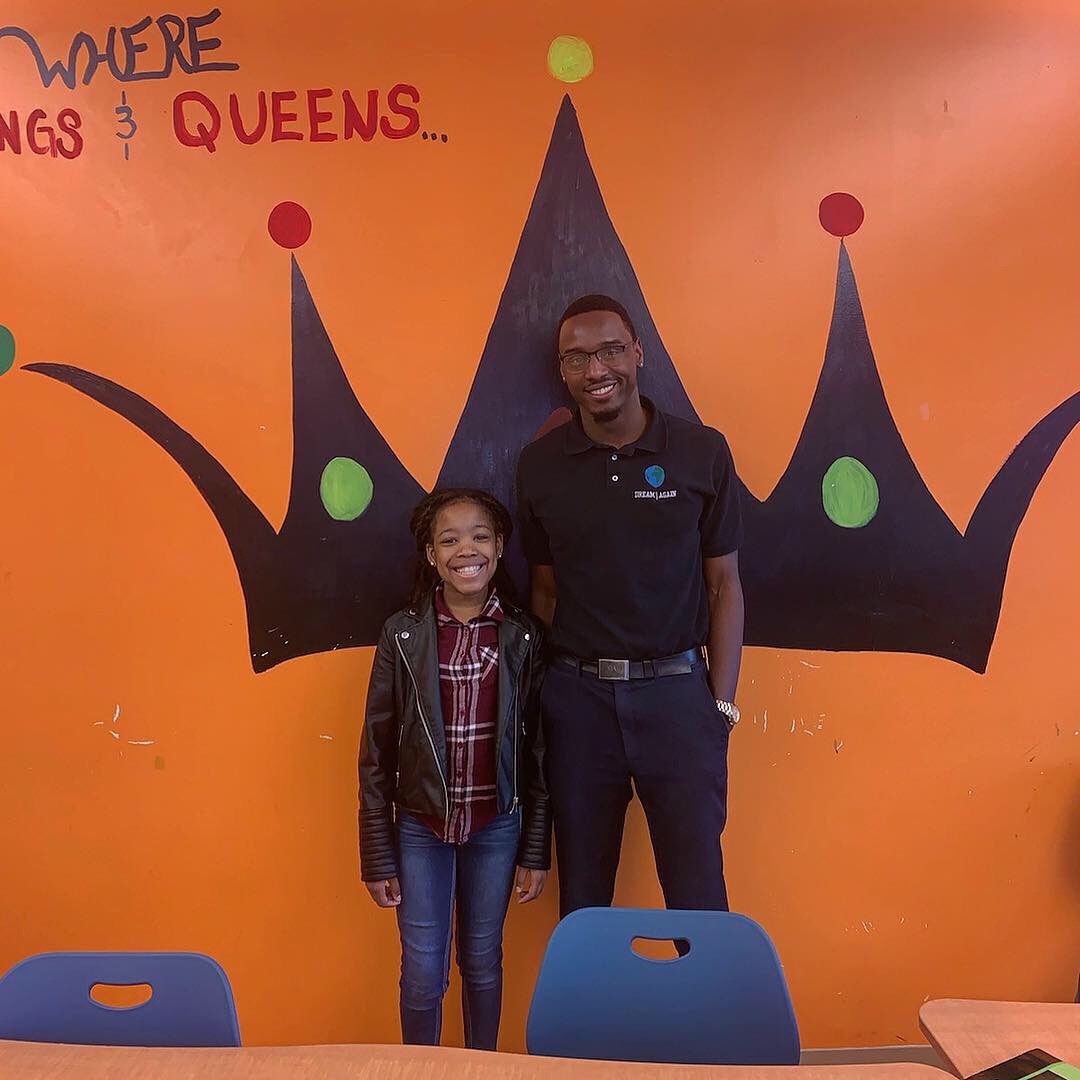

Actively Moving Forward is another HealGrief program. Best known as AMF, it began with college students supporting other college students through their grief journey. It evolved into a program supporting all young adults, allowing them to communicate with each other in a way they communicate best—digitally. It’s an app that is a hybrid of a social network, database of resources, and a notification center for daily inspirational quotes. It also offers a community board for posting.

The app since has extended to people of all ages, hosting separate and distinct communities for young adults and for those who are over 30. App members can participate in regularly-scheduled virtual support groups and in book clubs.

“It’s such a gift to hold a safe and sacred space for people to share their most intimate feelings about something so deep within them. And it’s a gift to witness deep friendships emerging from this thing called grief,” Solomon said. “None of this costs our members anything. They can sign up for as many kinds of virtual support as they like.”

“Our members have learned that although grief has a start date, it doesn’t have an end date. Grief is an uninvited companion that we somehow learn to take with us through the rest of our lives,” she observed. Solomon says her work in bereavement care “teaches me to live life to the fullest, to never wait for tomorrow. To tell my family and those I love how much I love them and how important they are to me. It’s a daily reminder of how precious life is and how important it is to be present for those we love.” The site averages about 10,000 new visitors each week, according to Solomon. Poignantly, she reports that the most-visited page by far is “Death of a Child.”

Services are offered at no cost to the site’s users. Solomon reports that HealGrief.org, as a 501c3, accepts donations and has received grants. One was from Funeral Service Foundations, who recognized the importance of the app. Traditional bereavement care was disrupted during the time that Covid shutdowns were most intense, according to Solomon. People who work in bereavement care were unsure of the best ways to serve their clients during that time, so many referred them to HealGrief.org.

“Being virtual, we were in a prime position as the continuum for serving those in need,” Solomon said. “In-person care for many will always be necessary, however we have found that people tend to be more comfortable and share more from the comfort of their own homes,” she explained. “We have been able to serve in new ways. People with disabilities or who don’t have transportation, for example, now can access the support they need too.”

“Support is crucial,” Solomon reflects. “Lack of support can lead to poor coping skills, which can lead to addictive behaviors, suicidal ideology, etc. Grief can change the trajectory of a person’s life. We find that when people try to put their grief into a box or shut down their feelings, this tends to trigger displaced emotions and manifest in ways that they themselves often don’t understand. I was a clear example of this.”

The organization provides training to university faculty, staff, and social work students. It works to help faculty become more grief-sensitive and to understand the needs of grieving young adults through its Grief Sensitive Campus Initiative.

“Many institutions offer bereavement leave to faculty,” she observed, “but not to students. Students have had to negotiate their workload with each professor, interfering with their need to be with families. And upon returning, grieving students can’t be expected to function equally with their peers.”

Christine Colbert holds a master’s in journalism. She has written for and edited varied media. Her preferred “beat” is good news.