New Orleans is passionate about its bread, especially when it comes to the po-boy. Some say the city’s signature sandwich, usually stuffed with fried oysters, shrimp, roast beef, sausage, or meatballs, isn’t the real deal unless it’s served on a locally baked Leidenheimer loaf.

“The most important part of the po-boy is the bread,” said Joanne Domilise, one of the family members who runs Domilise’s Po-Boy & Bar. “Leidenheimer’s bread has a crispy crust and is light and airy inside. It’s not bready or doughy like a hoagie or submarine. If you don’t have the right bread, it’s just not a po-boy.”

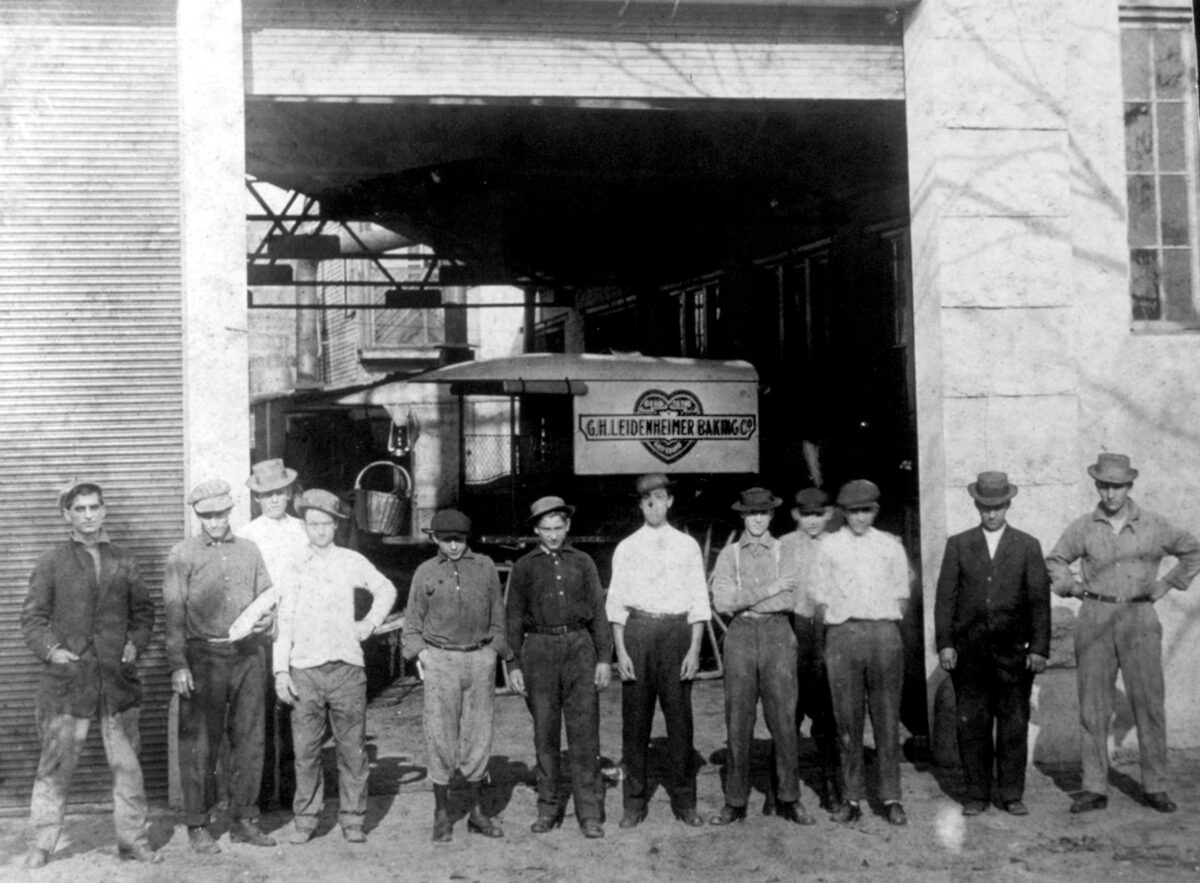

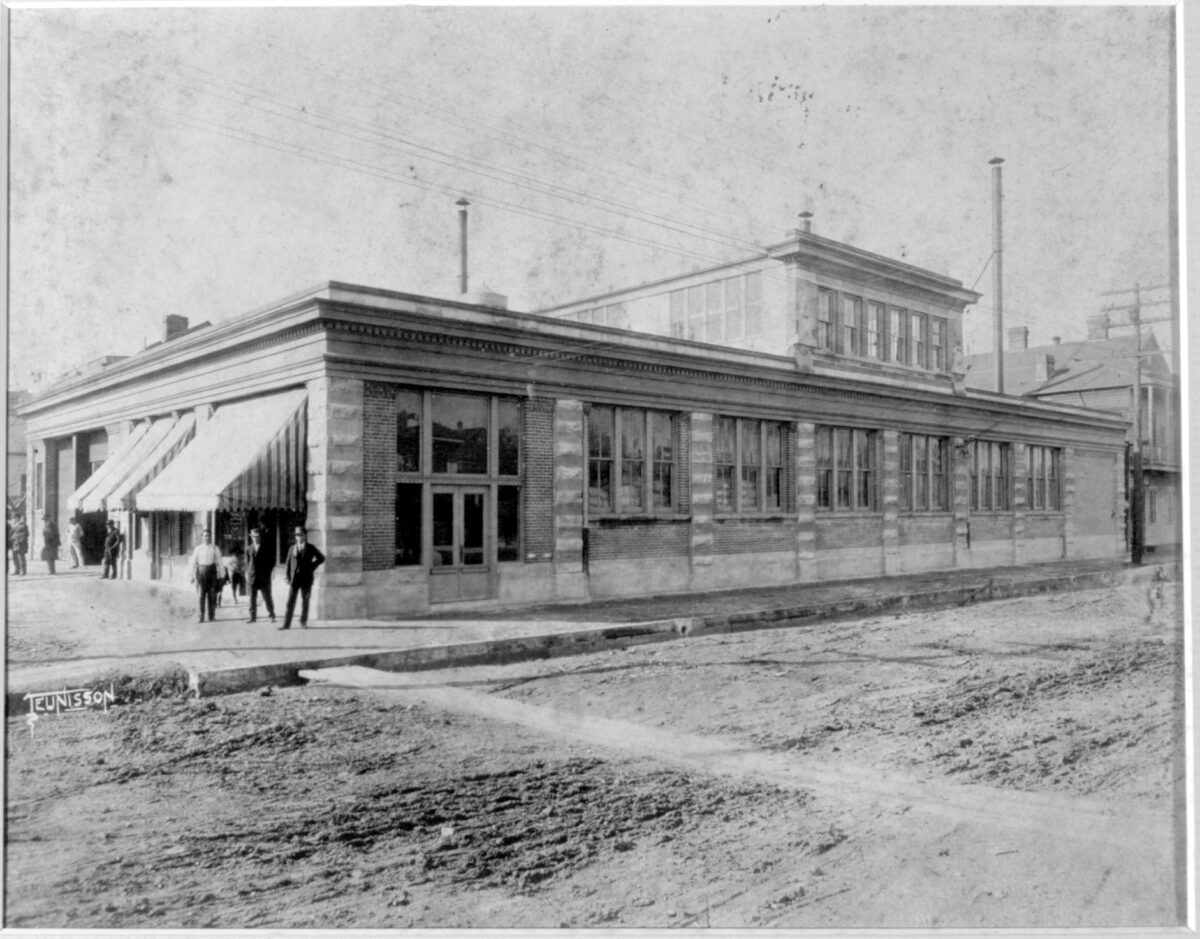

Like Domilise’s, and many other local institutions, the G.H. Leidenheimer (pronounced LYE-den-high-mer) Baking Company is a century-old family food business. It’s been a hub of New Orleans French bread baking for 125 years.

A Family Legacy

Founder George Leidenheimer immigrated to New Orleans from Deidesheim, Germany in the late 1800s, and established his namesake bakery in 1896. Initially, he made the dark, dense brown breads popular in his homeland. But he found success perfecting lighter French-style breads to complement the local cuisine, which draws from the bounty of the Gulf waters and the city’s Creole and Acadian heritage.

As the nation’s interest in regional American cooking and artisan foods grew over the years, and New Orleans became a tourism hub known for its outstanding restaurants, recognition for Leidenheimer’s distinct breads grew.

Being a local family-run business was also important.

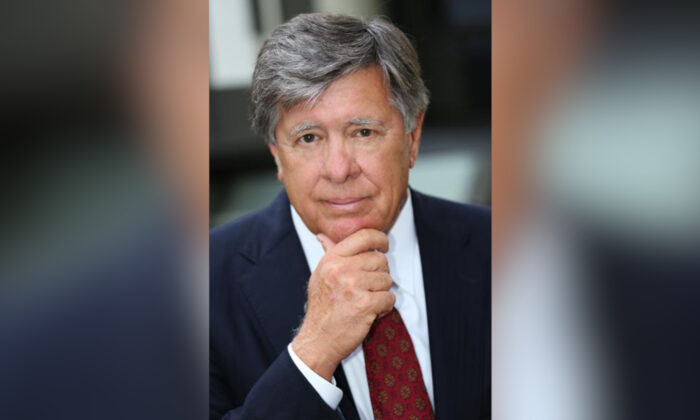

“Family culture is everything in New Orleans,” said Robert J. Whann IV, known as Sandy, a fourth-generation member of the Leidenheimer family. “People return home to this city to be with their families. That’s why it has many multigenerational families who run businesses.”

Whann’s grandmother was George Leidenheimer’s only daughter, Josephine. Her husband, Robert J. Whann Jr., took over the company with his brother, Richard.

Sandy Whann joined the company in 1986, after college, and today, he runs it with his sister, Katherine.

“I’ve been fortunate during my 35-year tenure to work with Katherine to manage the company. My brother-in-law, Mitch, has served as operations manager for 20 years. My son, William, and daughter, Katie, are now also involved with the company.”

Whann takes carrying on the family baking tradition seriously. You won’t see a gluten-free loaf coming out of this bakery.

“We produce traditional New Orleans French bread, and we are blessed that we are kept busy doing it. When we are approached about doing something new we have to consider it very carefully. We are not going to jump on the bandwagon and bend to trends,” he said.

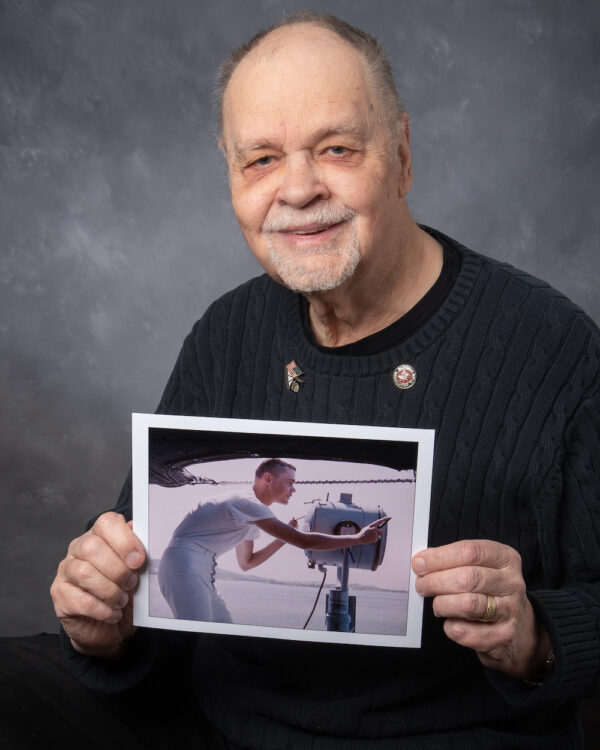

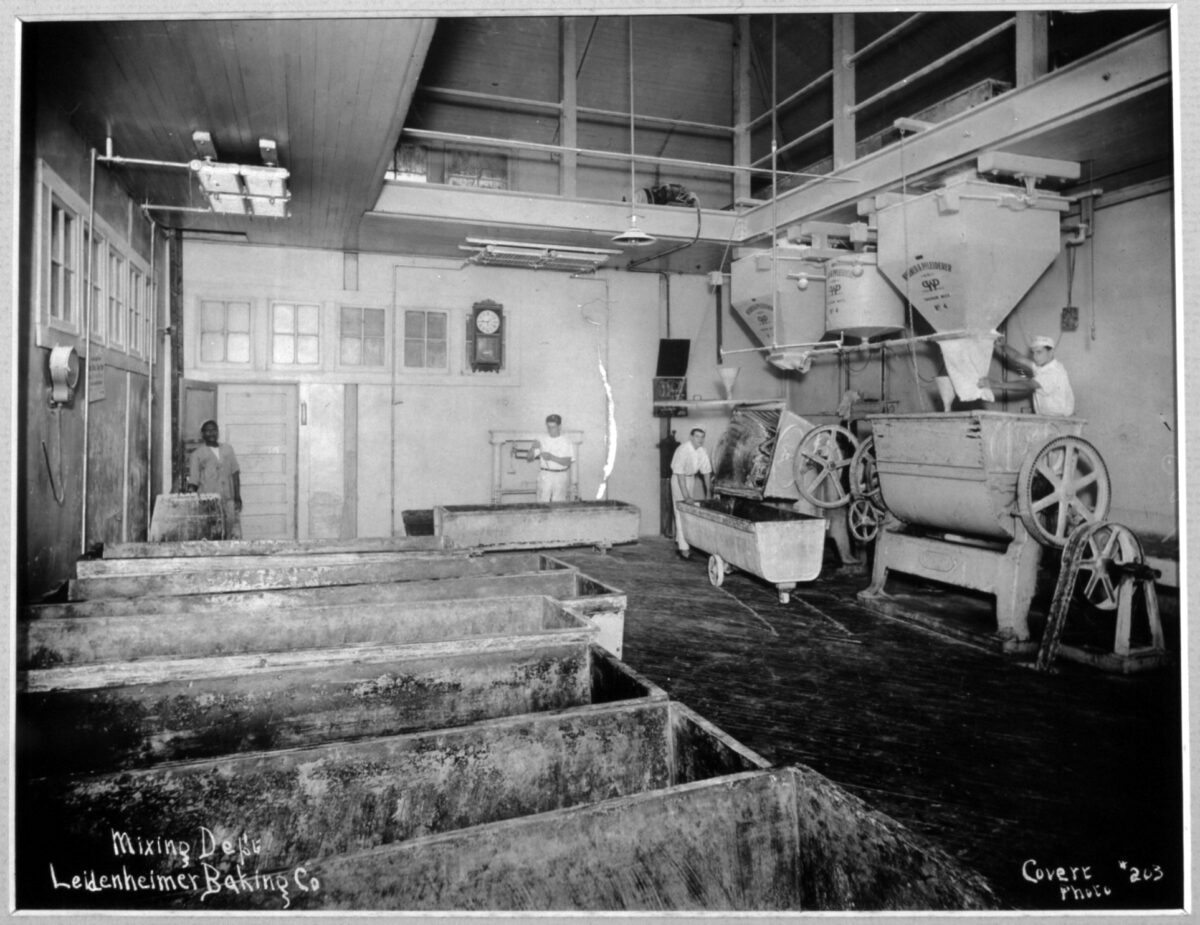

Since 1904, Leidenheimer’s baking headquarters have been in a large white brick building on Simon Bolivar Avenue in the central city. Many of the company’s 100 or so employees represent multiple generations.

“Being family-run with many long-tenured employees is a potent combination for success. We have route salesmen who have been with us over 40 years, and many bakery employees for 20 years,” said Whann.

A Time-Honored Process

My mother used to tell me New Orleans’s bread has a unique texture because of the water. Whann acknowledged that the local water has a good pH level for making bread, but explained the time-honored process in further detail.

Leidenheimer’s bread is made with flour, yeast, water, and a little salt and sugar. Lard was removed in the 1960s and replaced by small amounts of soybean oil. The flour is milled from a high-gluten spring wheat, sourced in the Dakotas and shipped to Ardent Mills near Baton Rouge. The company has been milling flour for Leidenheimer’s for 70 years.

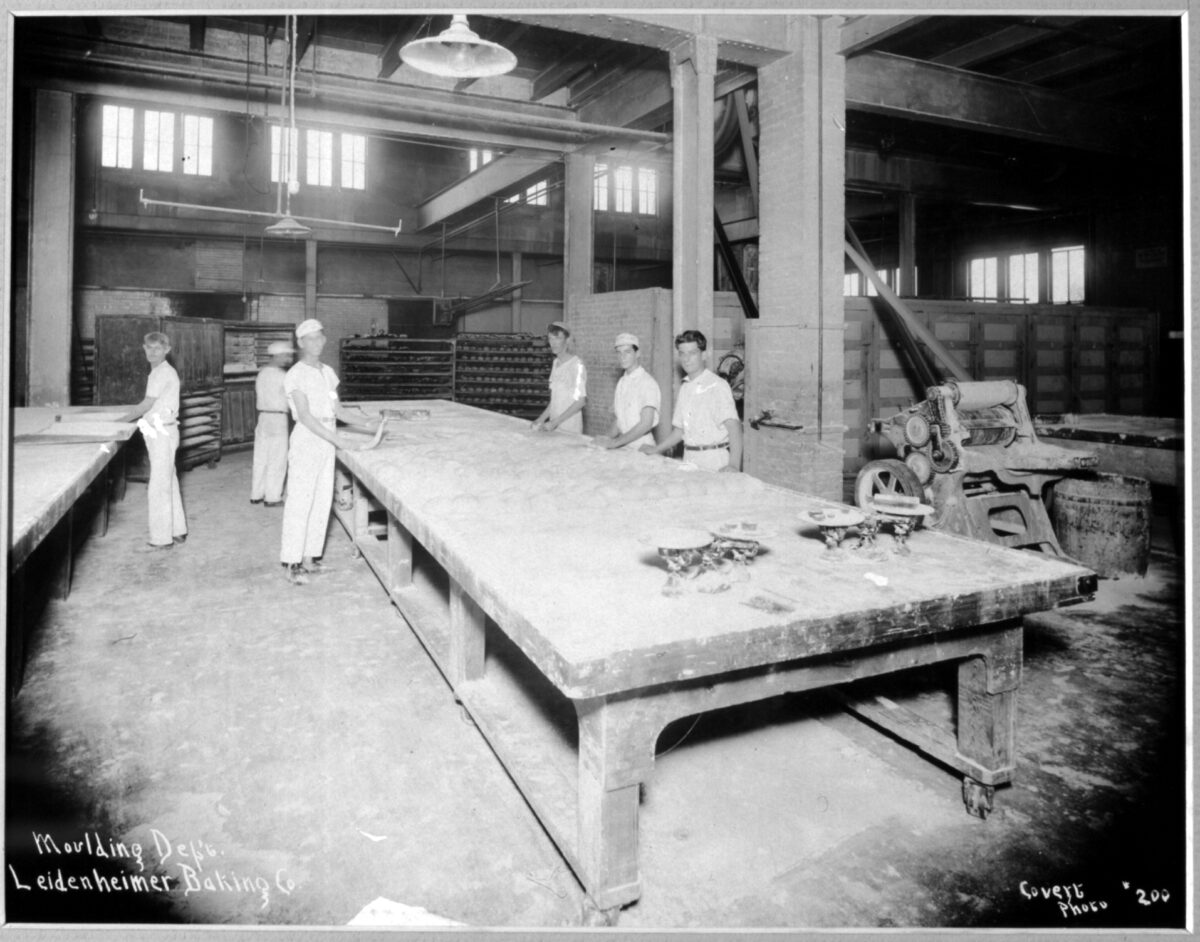

“We start with the best ingredients and let time and temperature do their work through natural fermentation,” Whann said. “All our po-boy loaves are hand-stretched. Our bakery workers know by touch when the dough is right, from how much water to add to how long to stretch it to achieve that light consistency.”

Once the dough is ready, the baking process involves copious amounts of steam and monitoring the temperature to achieve just the right texture.

Weather is also an important factor. “New Orleans is an inhospitable place for bakers. We have two seasons: It’s either hot and cold [in the winter] or hot and hotter [in the summer],” Whann said. “Our bakers need to be aware of the weather conditions since the dough is sensitive to atmospheric conditions such as humidity and temperature.

“For French bread, which is inherently light, on a day with 100 percent humidity, it acts like a sponge. We have to bake the bread more to keep its texture. On colder days, we need to bake the bread less.”

Legendary Loaves

Leidenheimer produces a small variety of artisan breads, sold locally and distributed nationally. There are three main types:

Its signature pistolet is an oblong loaf with a very crisp crust and a fluffy interior—a texture many compare to cotton candy. Available in different sizes, up to 12 inches long, the pistolet is usually served warm, wrapped in white napkins, at fine dining restaurants like Commander’s Palace and Galatoire’s.

“I can always tell locals from the visitors when our pistolet is brought to the table,” Whann said. While visitors reach for a fork and knife, “locals just grab the bread and tear it apart with their hands to share with their table companions.” Either way, the light-as-air loaf is heavenly slathered with butter.

The po-boy loaf is a 32-inch-long French bread loaf used for the namesake sandwich. Unlike a traditional French baguette, which has tapered ends, a po-boy loaf, like the pistolet, is uniform from end to end.

The muffaletta is a large, round, seeded bread used to make a sandwich by the same name. Another New Orleans icon, the muffaletta sandwich is a savory combination of salami, ham, provolone cheese, marinated olives, and giardiniera, said to have been created in 1906 by Central Grocery in the French Quarter, to feed the Italian immigrants who worked at the nearby dockyards.

Locals Loyal to the Last Crumb

New Orleans has many family-run bakeries known for their signature products, whether cakes, pastries, or breads. But when it comes to New Orleans French bread, loyalists always look to Leidenheimer’s.

“Leidenheimer’s is the only bread in town with that crackly crust. It’s both an art and a science to make it with such consistency,” said Justin Kennedy, general manager and head chef at Parkway Bakery and Tavern. They sell about 2000 sandwiches a day. “We lightly toast our bread to bring out that crunch even more.”

That loyalty transcends distance. At Local Catch Bar and Grill in Santa Rosa, Florida, chef Adam Yellin, a transplant from New Orleans, only uses Leidenheimer bread for the restaurant’s po-boys. “When I was living in New Orleans, we’d squeeze the bread a little and listen for the outside crunch to know it was fresh,” he recalled.

“Good to the last crumb,” is Leidenheimer’s slogan—and it’s true. New Orleanians know to ask for extra napkins and a crumb catcher when they tear apart a pistolet or devour a po-boy. All that crust leaves a beautiful mess of crumbs!

The Po-Boy: Perfect End-To-End

The history of the po’boy explains how the unique loaf for the sandwich was created.

Louisiana-born brothers Bennie and Clovis Martin worked as streetcar conductors before opening Martin Brothers Restaurant in the French Quarter in 1922. In 1929, when the streetcar workers went on strike, the Martin Brothers, sympathetic to the workers’ plight, gave them free sandwiches filled with fried potatoes, gravy, and bits of roast beef on French bread loaves. When a striking worker would come into the restaurant, one of the brothers would call out, “Here comes another poor boy.”

As Whann tells the story: “Back then, the bread was a traditional French baguette with tapered ends. The person who received the middle portion of the sandwich made out like a bandit, but those with the ends were not as fortunate. The Martin Brothers asked a local baker, John Gendusa, to make a 32-inch loaf that could be cut into equal-size sandwiches. No one would be stuck with the ends.” The sizable, shareable sandwich was a hit and became part of the Martin Brothers regular menu.

Now, the ubiquitous sandwich can be found on many menus, from small po-boy shops to fine restaurants throughout New Orleans and beyond.

Melanie Young writes about wine, food, travel, and health. She is the food editor for Santé Magazine, co-host of the weekly national radio show “The Connected Table LIVE!” and host of “Fearless Fabulous You!” both on iHeart.com (and other podcast platforms). Instagram@theconnectedtable Twitter@connectedtable