Adam Brand, fourth-generation co-owner of M&S Schmalberg Custom Flowers, joined his family business about 12 years ago. “My dad was a flower man. I never really appreciated what that meant,” said Brand. “The business was 90 years old at the time, and I didn’t appreciate that either.” It was only when Brand started coming into the factory and seeing the passion and admiration through the staffs’ eyes, that he finally realized the importance of his family legacy. Brand’s pride and ambition in continuing this legacy stem from his ancestor’s love for the craft. “It’s absolutely morphed into something that I love, and I’m proud of,” he said.

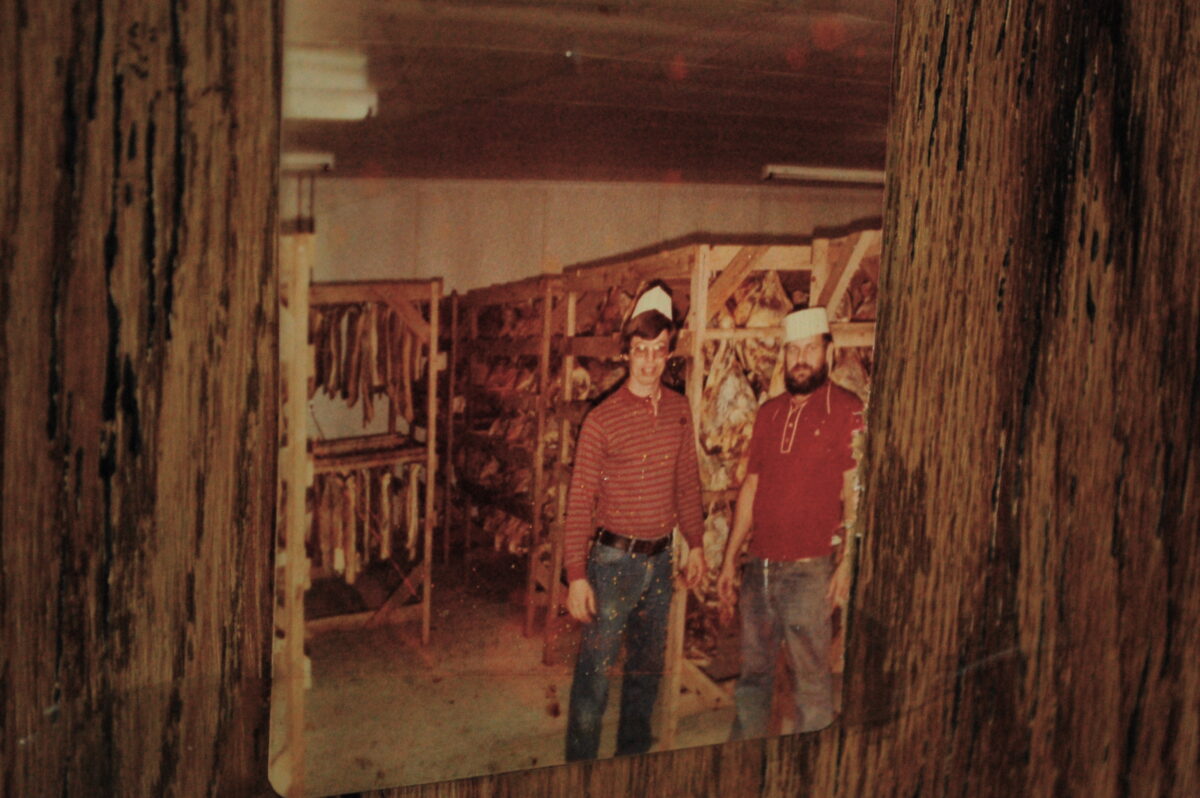

Located in the heart of New York City’s historic Garment District, Schmalberg is the last remaining artificial custom flower factory in the entire city. The flowers are still handmade by expert flower makers, using traditional techniques and vintage molds passed down in the family.

Schmalberg has worked with numerous top fashion designers like Vera Wang, Marchesa, Oscar de la Renta, Ralph Lauren, and J. Crew. The company has also produced flowers for theatrical productions and TV shows—typically used for costumes or to emulate flowers in vases—like “The Gilded Age” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.” “We’ve worked with the New York City Ballet, the Metropolitan Opera, the Australian Opera, and even Walt Disney,” Brand said.

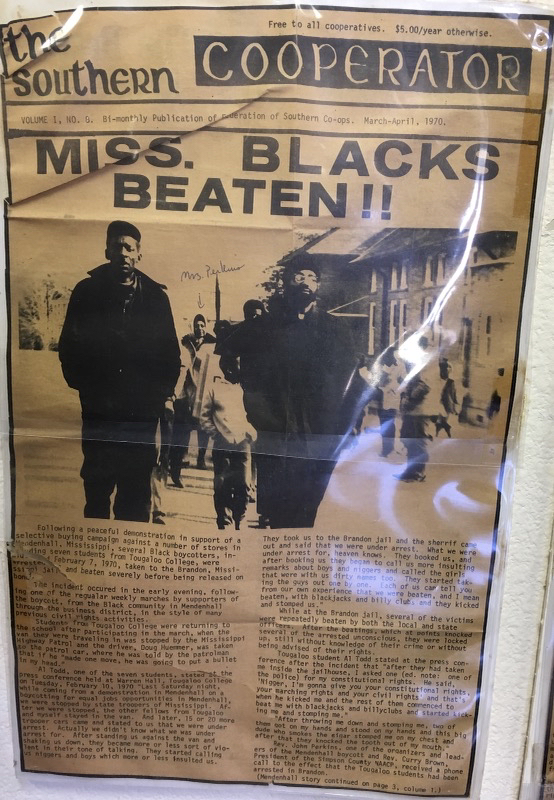

The company was founded by brothers Morris and Sam Schmalberg in 1916, when the Garment District was considered the fashion manufacturing capital of the world. “There’s a picture in the hallway of 35th Street in the ‘40s,” said Brand. “And you see all the trucks and pushcarts. It was like a highway of just fabrics and dresses going from one factory towards another to the designer.”

Brand’s grandfather, Harold, was a Holocaust survivor from Poland. Harold was 17 years old, and living in their attic, when he first started helping out at Schmalberg, a company started by his uncles. Harold eventually got married and had children—Adam’s father, Warren Brand, and Warren’s sister, Debra—who took over as their father got older. Adam now runs the family business, assisted by his team of expert flower makers.

Traditional flower making is on the decline, as an increasing number of companies have turned to Chinese manufacturers and automation. “As the last competitors in New York closed down, a lot of the time, my dad would buy out their old tools,” said Brand. “There’s nobody who owns a factory like this that could make thousands, 10 thousand pieces or more, that pays New York wages. That’s really a true American-made company.” Every single flower that leaves their factory is proudly made with vintage molds that have remained in the family for decades.

The Gift of Flowers

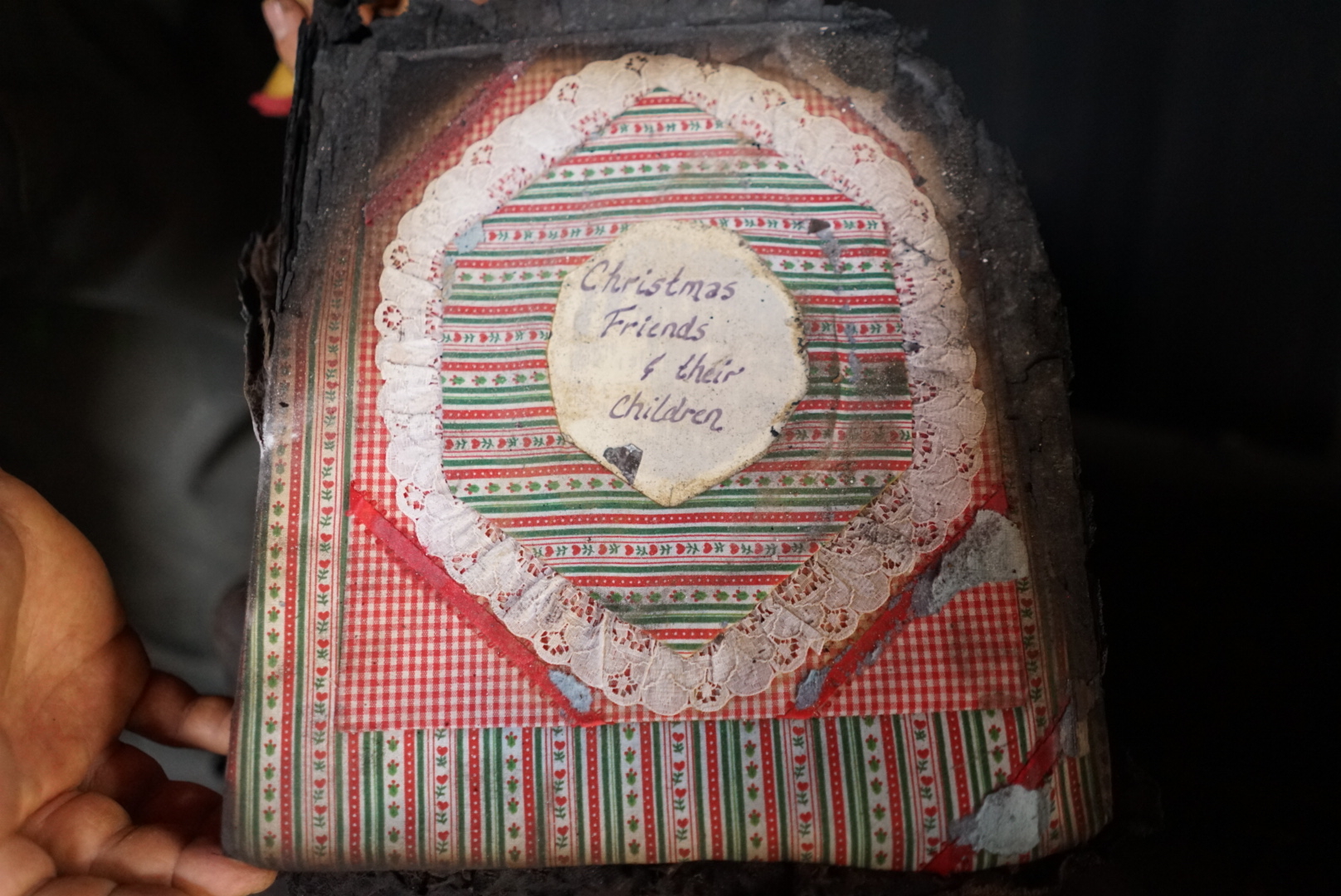

The company produces flowers using a variety of materials: silks, synthetic polyester, leather, suede, cotton, velvet, felt, and velour, but they are capable of using almost any fabric. “Most of what we do for clients is with their own material. That’s kind of what makes us special,” explained Brand. He has transformed many old wedding dresses that would have otherwise been forgotten in an attic somewhere, into beautiful flowers. Customers often gift them to their children or loved ones as tokens to cherish forever.

The company often gets approached by clients for unique projects, from making flowers for weddings, to crafting florals from curtain drapes that match a bouquet on the dining table. “We had a bride once send us fabric from her wedding dress, and we cut 100 flowers that she put on the plates of every guest,” Brand said. They also work closely with milliners who purchase flowers for their hats.

Brand has also worked with Eagles and Angels, a company that salvages veterans’ old army uniforms, and repurposes them into high-end accessories. Together, they took old uniforms and created limited-edition fabric carnations from them. Brand said that these types of custom orders give him the most joy, because the company is helping to repurpose something with a lot of memories into something beautiful, while offering loved ones a way to honor these heroes’ sacrifices.

The Process

One of the perks of working with an American-made company is the versatility, customization, and level of detail that goes into every product. “We did a project with Marc Jacobs, who wanted flowers with specific color graduations on them for a runway piece,” recalled Brand. “They came in on a Thursday and needed everything by the weekend, like five thousand flower petals.” The company brought fabric that had been pre-dyed in-house, and Brand’s team cut it to achieve the unique coloring they wanted on the flowers. This would not be possible if manufacturing was off-shored.

M&S Schmalberg has a special crafting process that allows them to produce detailed pieces for their clients. He explained that the company either offers its own fabrics, or clients send in their own. Then, the team will cut the material into panels and apply a fabric stiffener to it, to provide the material a little extra body, and allow its shape to hold better when placed in the molds. This also allows the embossing molds to imprint on the fabric better.

Brand explained that, in the old days, workers would use vintage die cutters and a rubber hammer—swinging hard over the mold—to cut the fabric. “As long as I’ve been alive, we don’t have to do that,” he said. To make the process easier and less hazardous, the company sawed the long handles off the molds and now uses a mechanical machine to automatically do the cutting. “We’re still using the same fundamental process, but we’ve modernized it. It’s safer; it’s faster, and it’s more efficient.”

Next the fabric is embossed with vintage molds inside a modified electric hydraulic press. The operator simply has to place the petals on the plate and push a button on the side, allowing the machine to press the flowers into unique shapes. “It’s just a more modern way, but still using the same molds that have been in the family,” said Brand. The final step in the process is assembling the flower petals to make a complete piece, which is done by slipping flower petals through a wire and using a special paste to hold them together.

Family and Legacy

Each member of Brand’s team has been working with the family for decades and has formed a special bond with them. “Alex, who does the cutting in the back, used to come over for Thanksgiving and different holidays when I was 3 or 4 years old,” Brand recalled. Miriam, who weaves flowers together by hand, “was here long before I was even born.”

Brand hopes to someday hand over the reins to his daughter, Skylar, who is just over a year old. “To be able to have the opportunity to pass it down would be really, really outrageous,” he said.