Her name alone is nearly poetic, but it is history and grandeur that give Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave her befitting nomenclature.

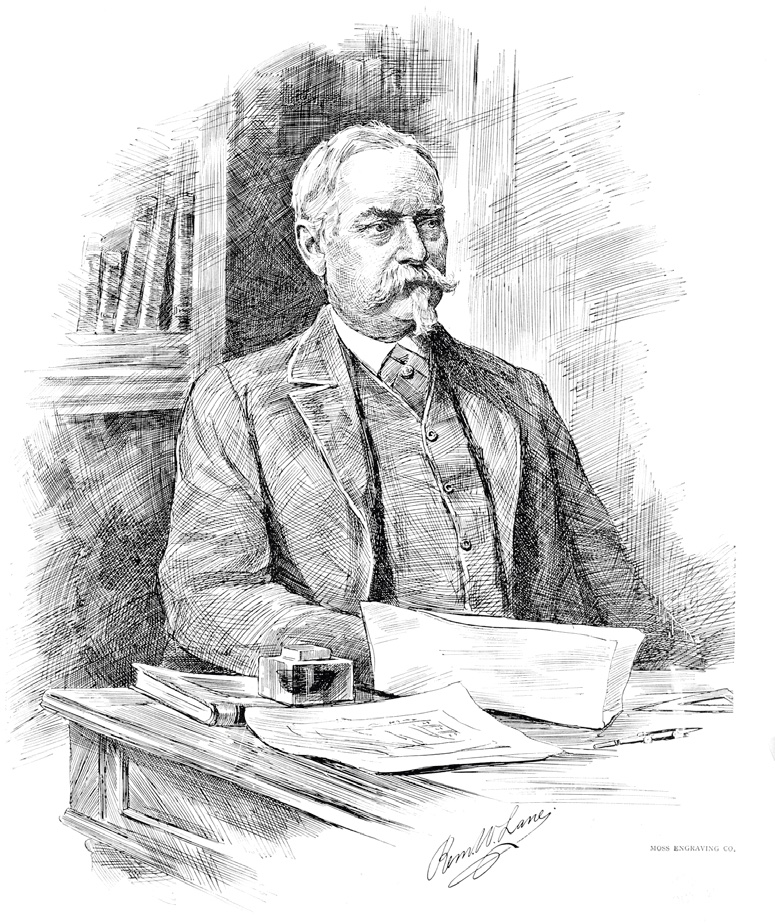

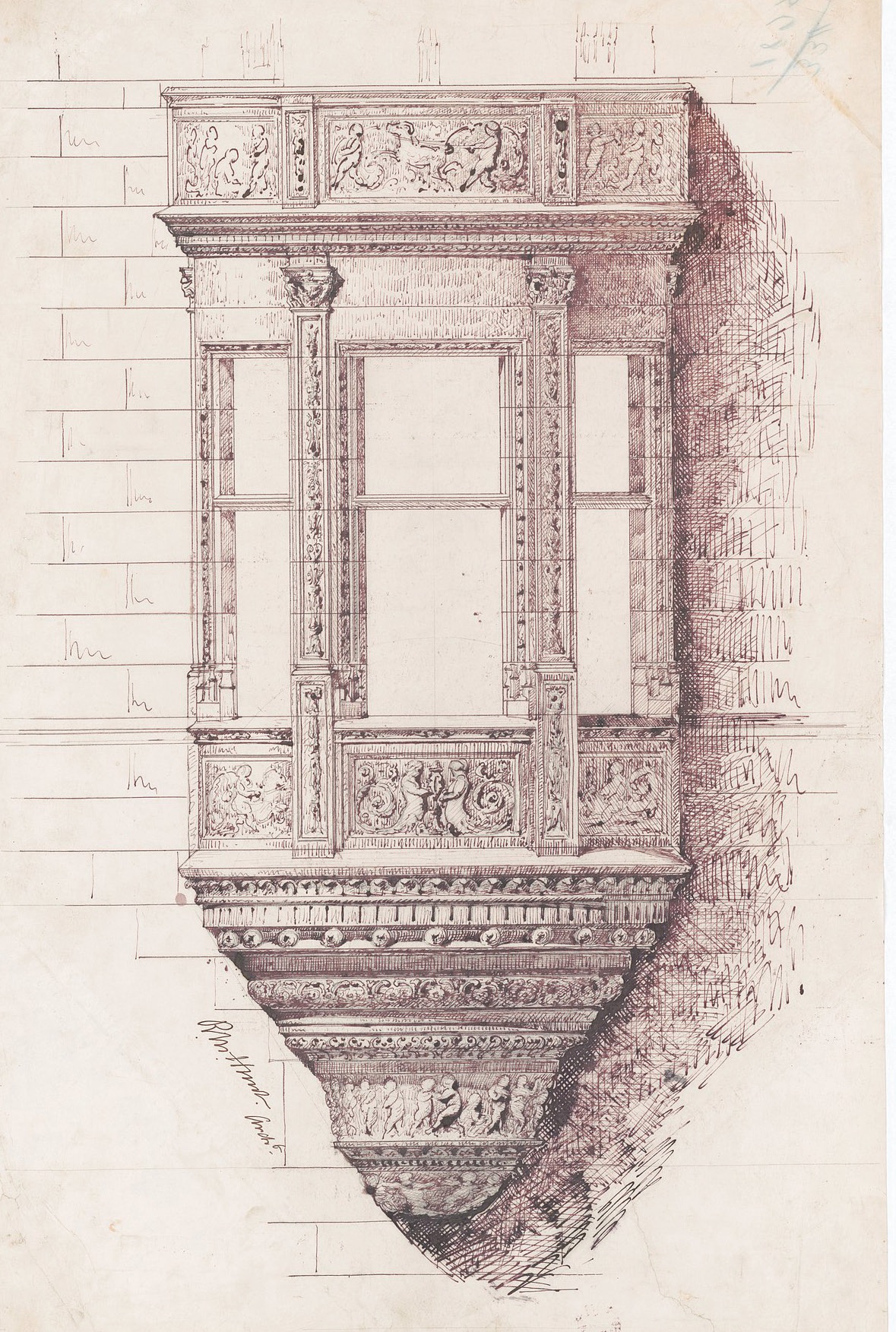

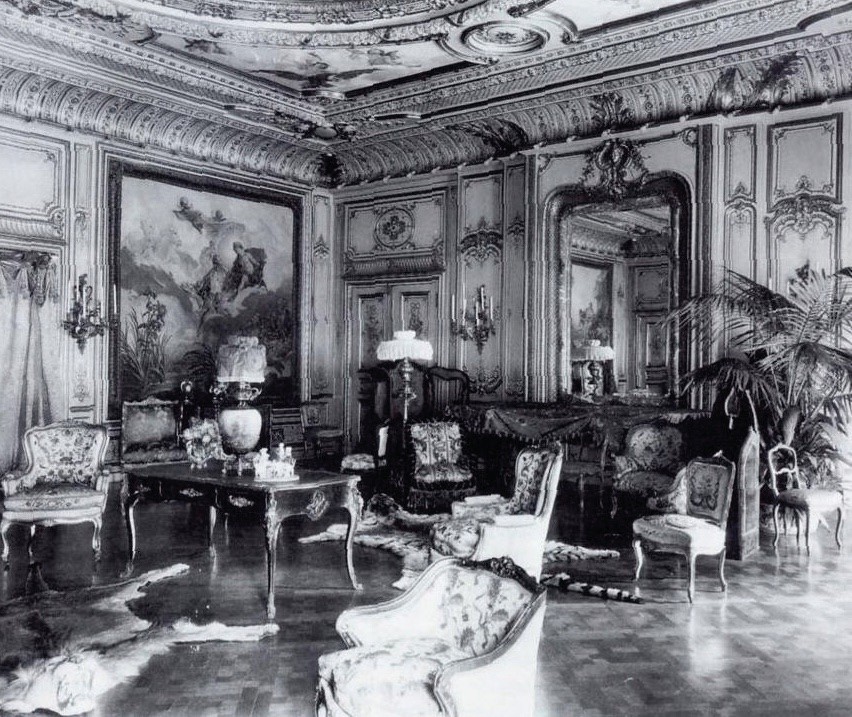

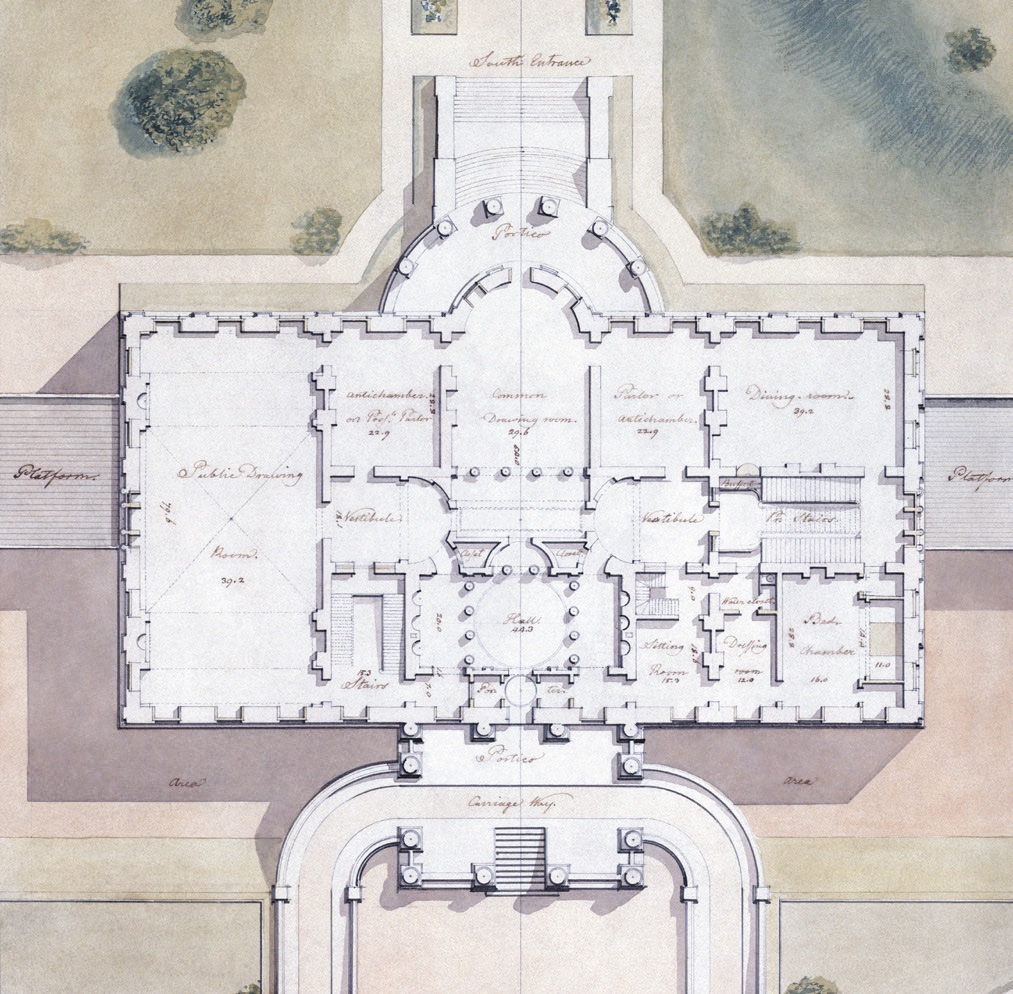

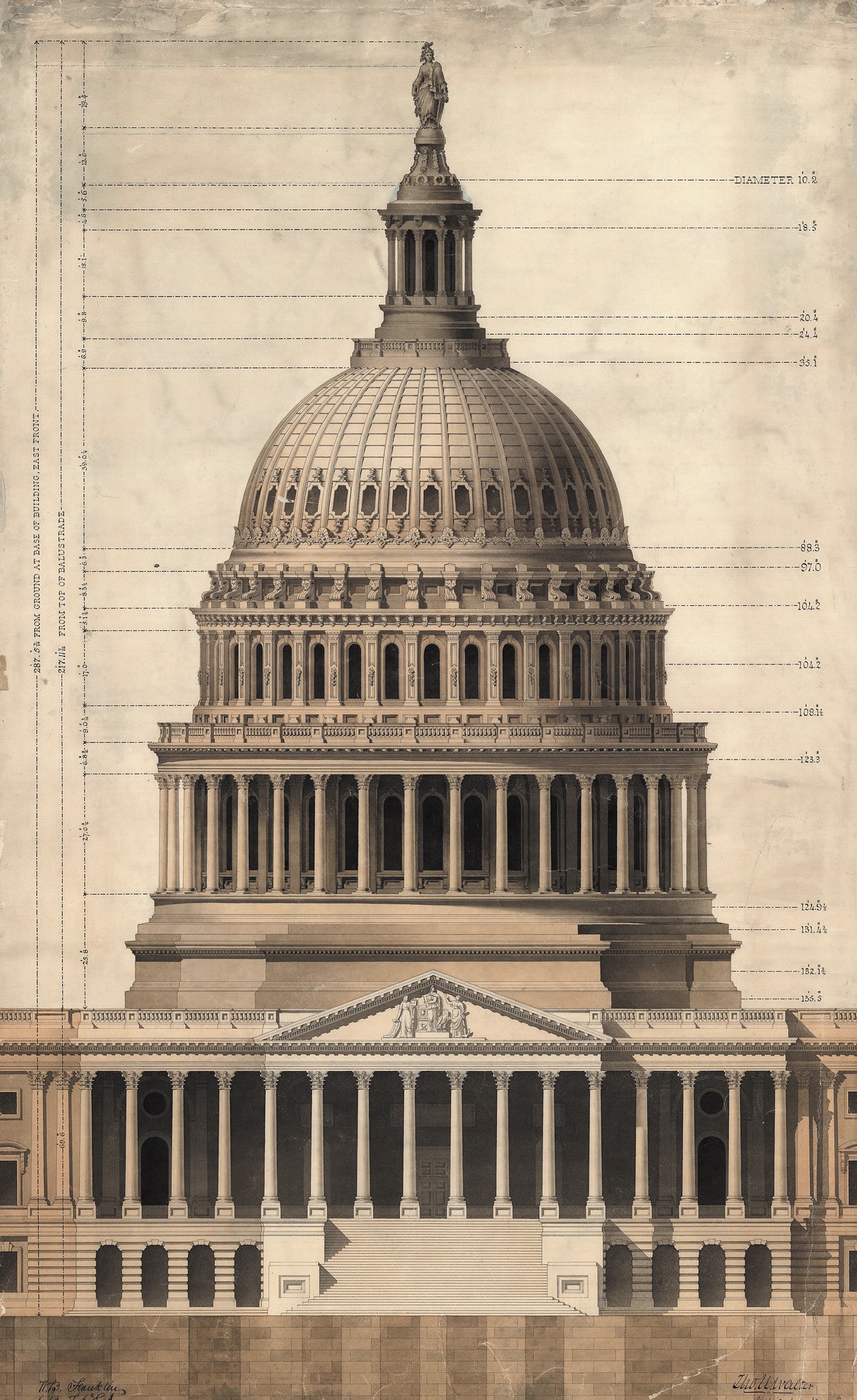

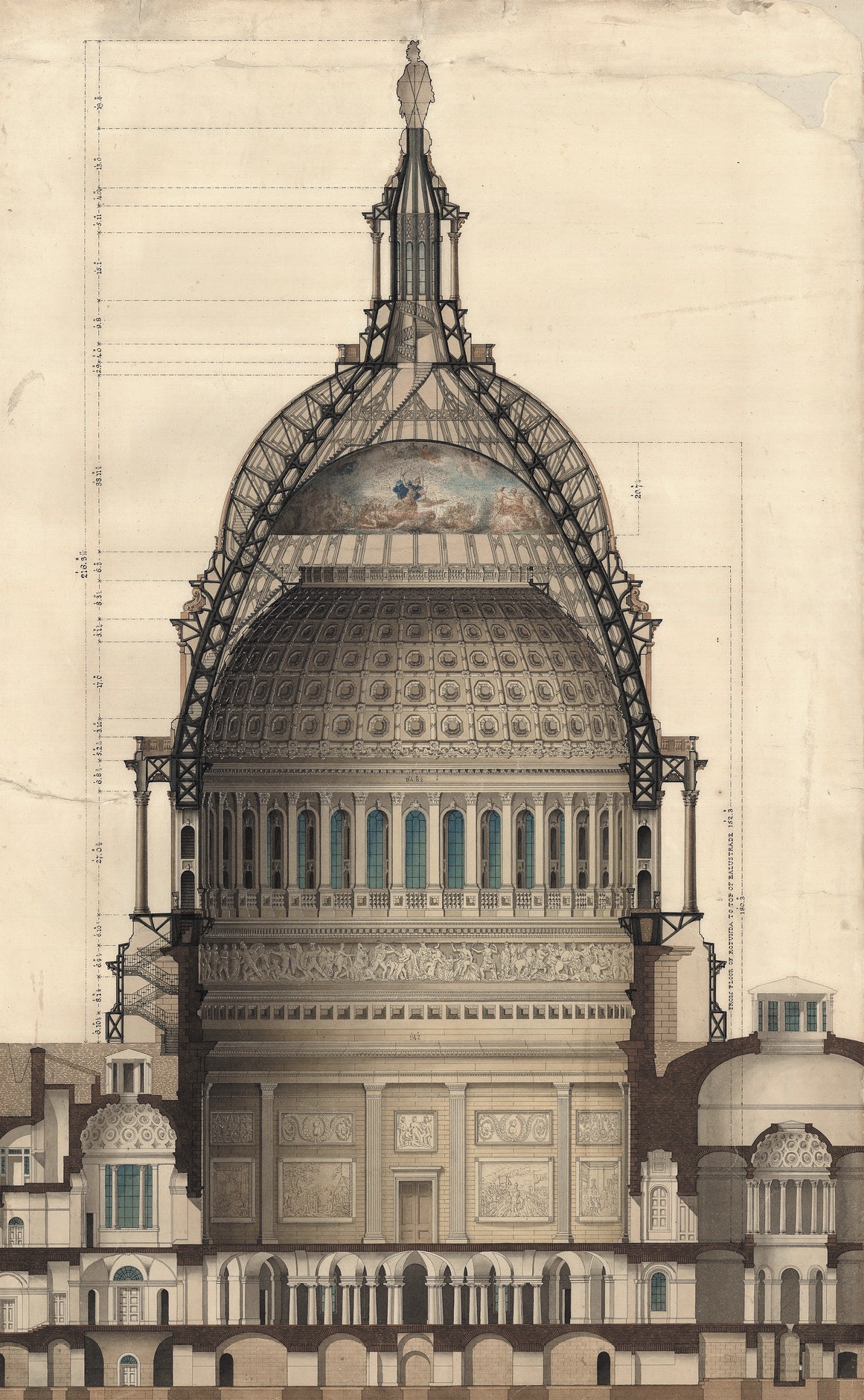

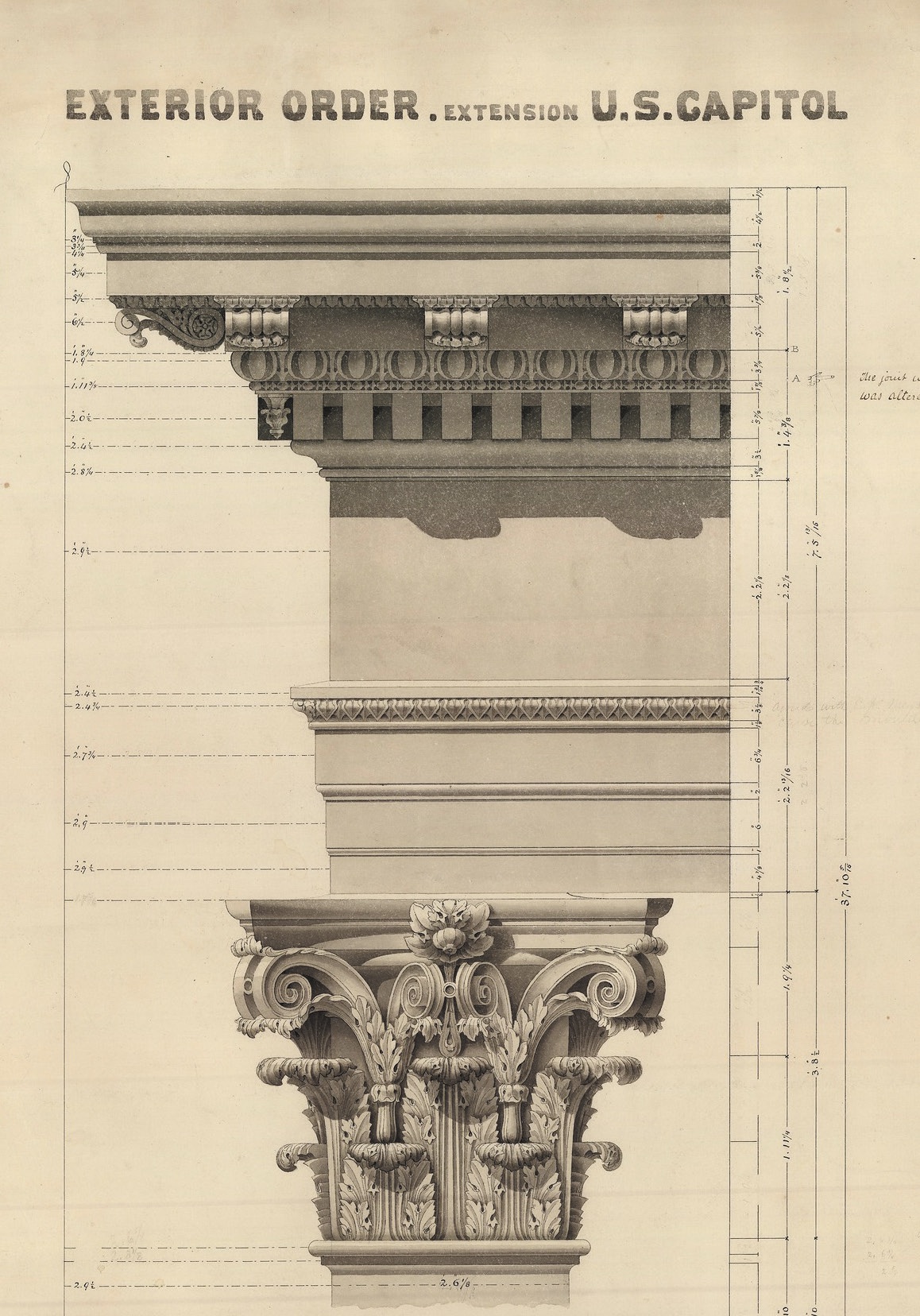

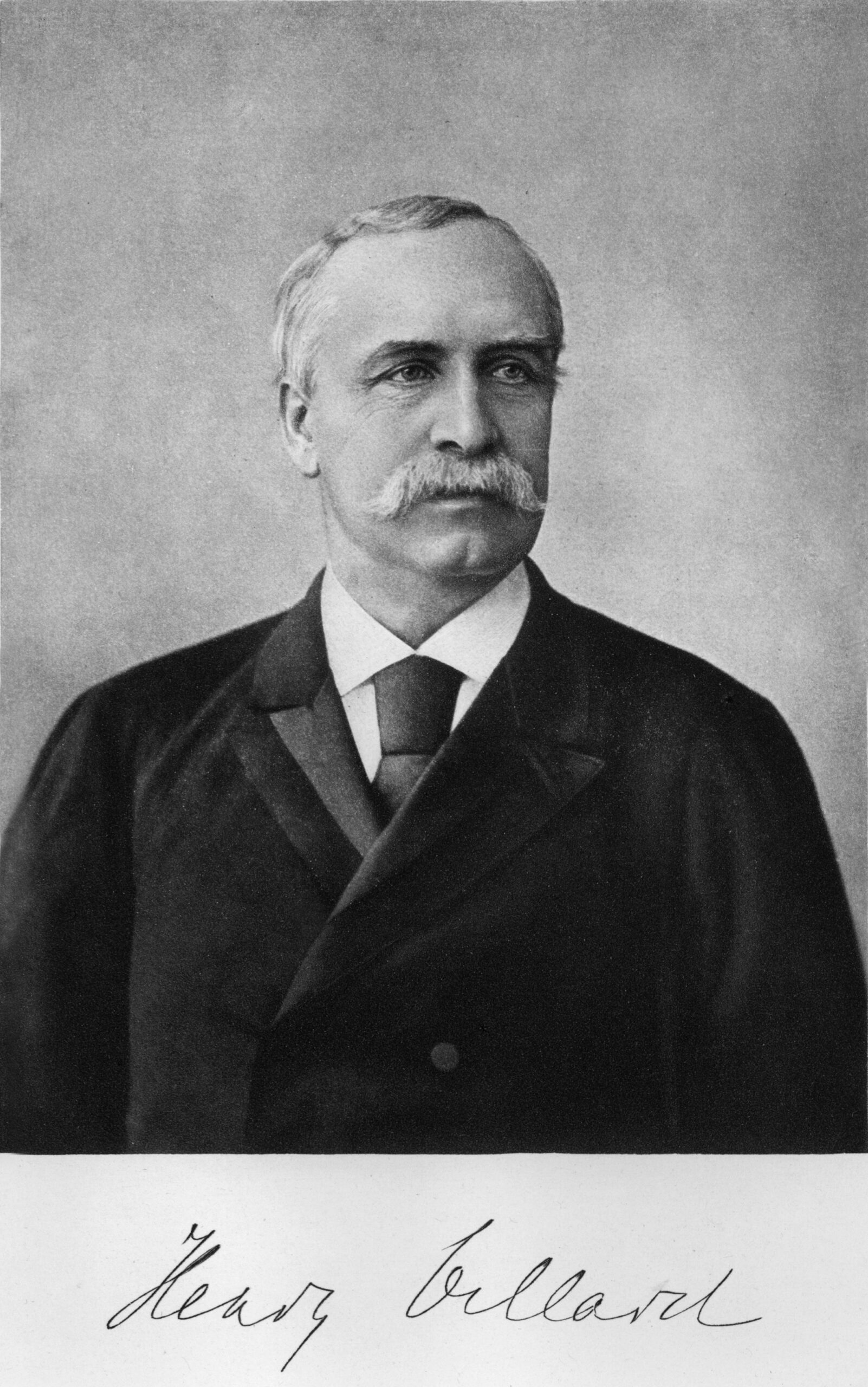

She is the great-granddaughter of Henry Villard, a Bavarian native who came to America with only 20 borrowed dollars in his pocket—only to make groundbreaking financial ventures and become president of the Northern Pacific Railroad and owner of the New York Evening Post. He also built what has become one of Manhattan’s most recognizable architectural landmarks: the Villard Houses, a Gilded Age mansion that today houses the luxurious Lotte New York Palace hotel.

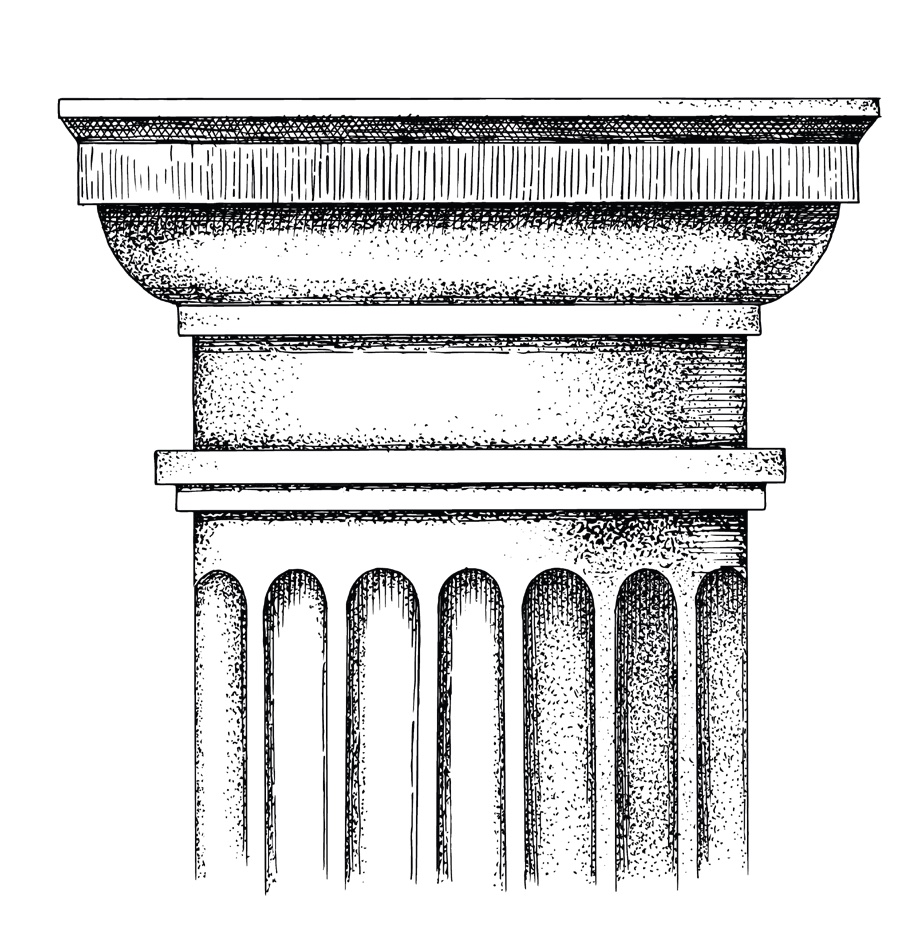

He believed so much in the greatness of America that he put his whole soul into the railway company—allowing it to complete the country’s second transcontinental railroad—and funded Thomas Edison’s early experiments in electricity, Alexandra reflected. Meanwhile, the Villard Houses remain one of the few surviving examples of stunning design by the acclaimed architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White.

The American Story

Villard immigrated to the United States in 1853 from Germany at the age of 18. Within five years of arriving in America, he mastered the English language and began working for leading daily newspapers at the time. Villard covered the famous presidential debates between Abraham Lincoln and Democratic Illinois senator Stephen Douglas over the issue of slavery. Lincoln took a shine to him, and included him in his entourage. Villard was the only correspondent, then working for the Associated Press, to accompany the president-elect on his inaugural train from Springfield, Illinois to the nation’s capital. Then, during the Civil War, he was a war correspondent for The New York Herald and later for the New-York Tribune. In his coverage, he made sure black soldiers were properly commemorated for their service.

He was there when Thomas Edison famously lit up the first incandescent light bulb at Menlo Park, New Jersey in 1879. Villard would later hire Edison to install lighting aboard his new steamship, the S.S. Columbia. That was the first commercial installation of Edison’s invented light bulb. The installation was successful as the ship made its trip around South America. “Of all of my patrons,” Edison said, “Henry Villard believed in the light with all his heart.”

In 1881, Villard secured control of the Northern Pacific Railroad company through what modern-day finance would call a leveraged buyout. At the time, Villard was the president of major railway companies operating in the Pacific Northwest. But one major competitor, Northern Pacific Railroad, stood in the way. He started buying shares of the company quietly. But it was not enough to gain control. He came up with the idea, known as the ”blind pool,” of raising money for the venture by asking his friends to invest in a secret opportunity. By not revealing the plan, the investors became eager to get in on the novelty. Meanwhile, his intentions would be hidden from the competitor company. The tactic worked, and he became president of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Later, he bought two of Edison’s electric utility companies, Edison Lamp Company and Edison Machine Works, and formed them into the Edison General Electric Company in 1889. He served as president until its reorganization in 1893 into the General Electric Company.

Villard built his wealth from the ground up and was generous with it, paying off debts for universities and financing some of America’s most iconic colleges and architectural preserves, including Harvard University, the University of Oregon, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He was so inspiring to his great-granddaughter, Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave, that she honored his legacy in a 2001 biography co-authored with John Cullen called “VILLARD: The Life and Times of an American Titan.” The book tells of his remarkable rise from humble beginnings, eventually becoming a powerful financier and befriending luminaries like then-general Ulysses S. Grant (while covering the Civil War), and steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, among many others.

The Descendant

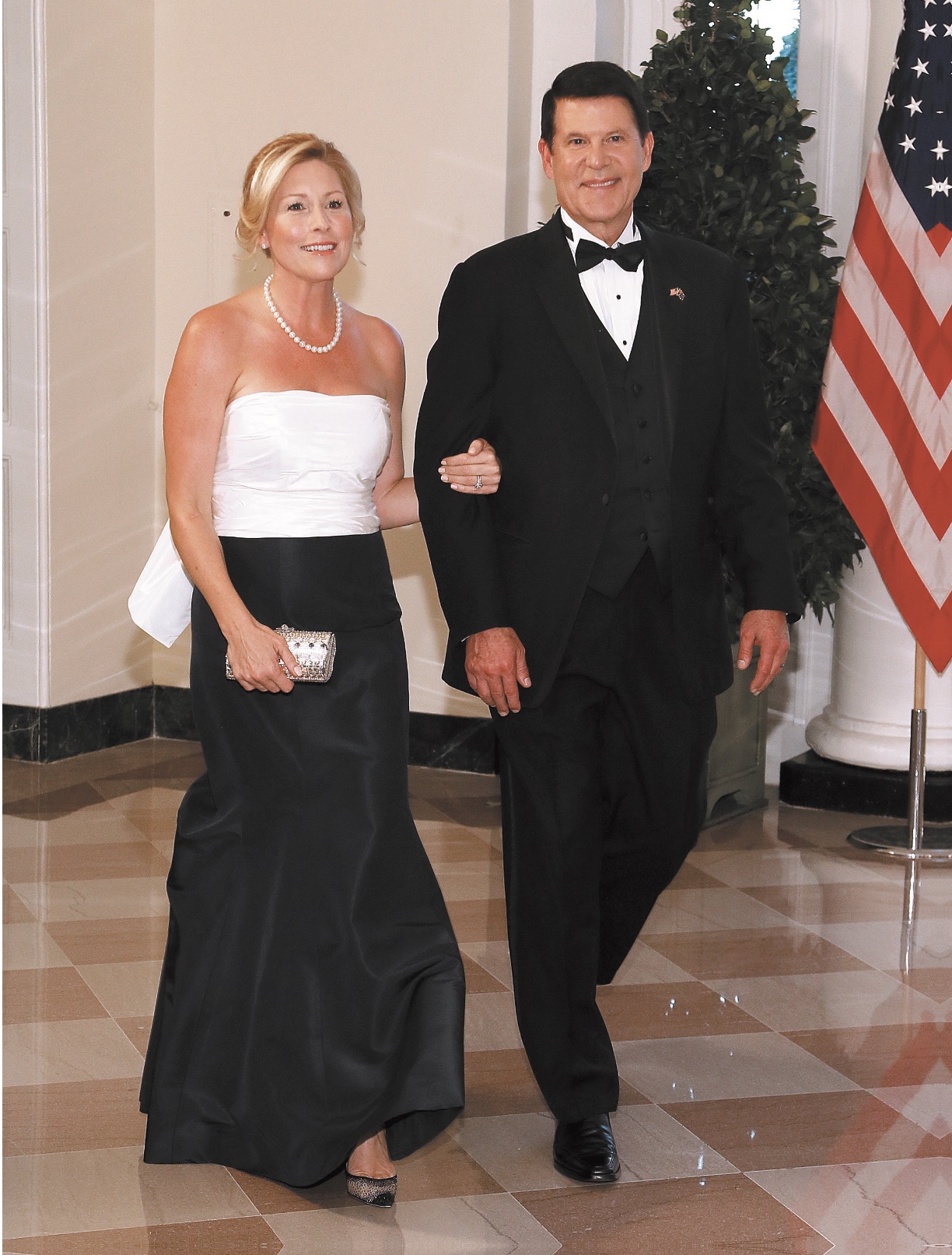

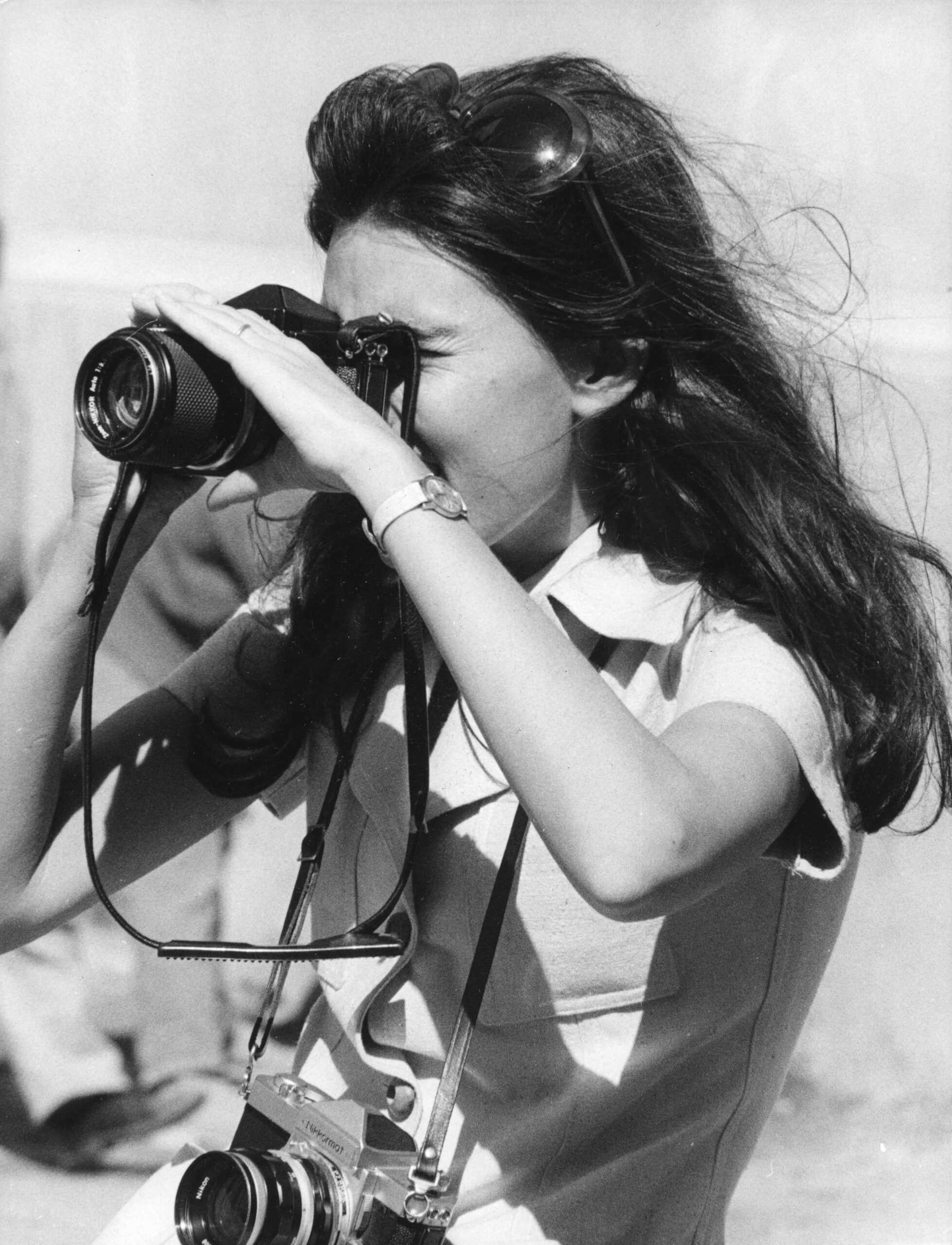

As a photojournalist, Villard de Borchgrave built a reputation on the merits of her own talents, with her work appearing on the covers of international magazines such as Newsweek and Paris Match. The late president of Egypt Anwar Sadat, Henry Kissinger, and the late U.S. president George H.W. Bush are among the many world leaders she photographed, and her portraits hang in government offices around the world.

She went on to establish a charitable organization called the Light of Healing Hope Foundation, which gifted books of hope to comfort patients receiving treatment at hospitals and hospices. With an eye toward helping those in the military, her foundation donated thousands of gifts to the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Navy Seal Foundation, Wounded Warrior Project, and American Gold Star Mothers. During its 12 years of activities, her organization also provided uplifting books and journals to several children’s facilities, including St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Ronald McDonald House Charities, and the Wendt Center for Loss and Healing. Villard de Borchgrave donated over 70,000 gifts which included her books of poetry and musical DVDs, for those who could not read, to over 100 medical centers nationwide. She developed and shared a total of eight inspirational publications including her first book, “Healing Light: Thirty Messages of Love, Hope, & Courage.”

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, United Nations secretary-general during the 1990s, wrote the foreword for “Healing Light.” Villard de Borchgrave and her husband Arnaud, who enjoyed a long career as chief foreign correspondent for Newsweek, had become friends with Boutros and his wife Leia while in Cairo in the 1960s. The couples were having dinner together in Paris when Villard de Borchgrave asked him to write the foreword, and so he did. “He just took a paper napkin on the table,” she recalled, and “penned it.”

Despite her many accomplishments, Villard de Borchgrave is most proud of her long marriage. She and her husband Arnaud, who passed away in 2015, were bonded for more than 45 years by their love of adventure and for each other. “In the 47 years since the first moment we met, Arnaud never failed to inspire me with his courage and determination,” Villard de Borchgrave passionately professed.

She also humbly pays homage to her parents, describing her mother as “a warm and giving person” and her father as someone who instilled a good work ethic in her, having worked on the U.S. Marshall Plan that helped rebuild European countries after World War II. Most of all, Villard de Borchgrave said, she draws inspirational humility from those who have been forced to overcome unspeakable tragedies. “I’m most inspired by the ability of those who are suffering,” she said, “to find a way to express gratitude despite the pain and hardship they are experiencing.”

Not only has Villard de Borchgrave honored her great-grandfather’s legacy through her biography about him, but has also, through her own work, continued to carry forth the same message of hope, courage, and resilience that he displayed throughout his life. “Henry Villard believed in America,” she said. “To this day, our country offers unique opportunities to anyone with the courage and determination to realize a dream, just as he did.”

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.