It was called everything from a male version of a Cinderella story to the greatest comeback in American sports history. It drew even those who are most uninterested in football to their television sets. Some football fanatics even couldn’t believe what they heard.

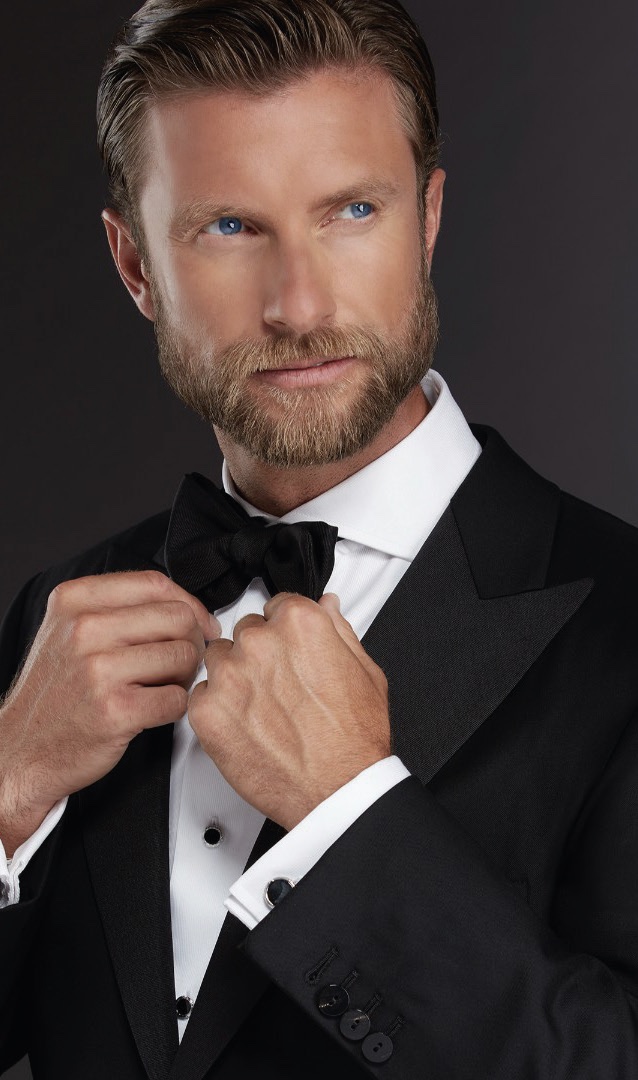

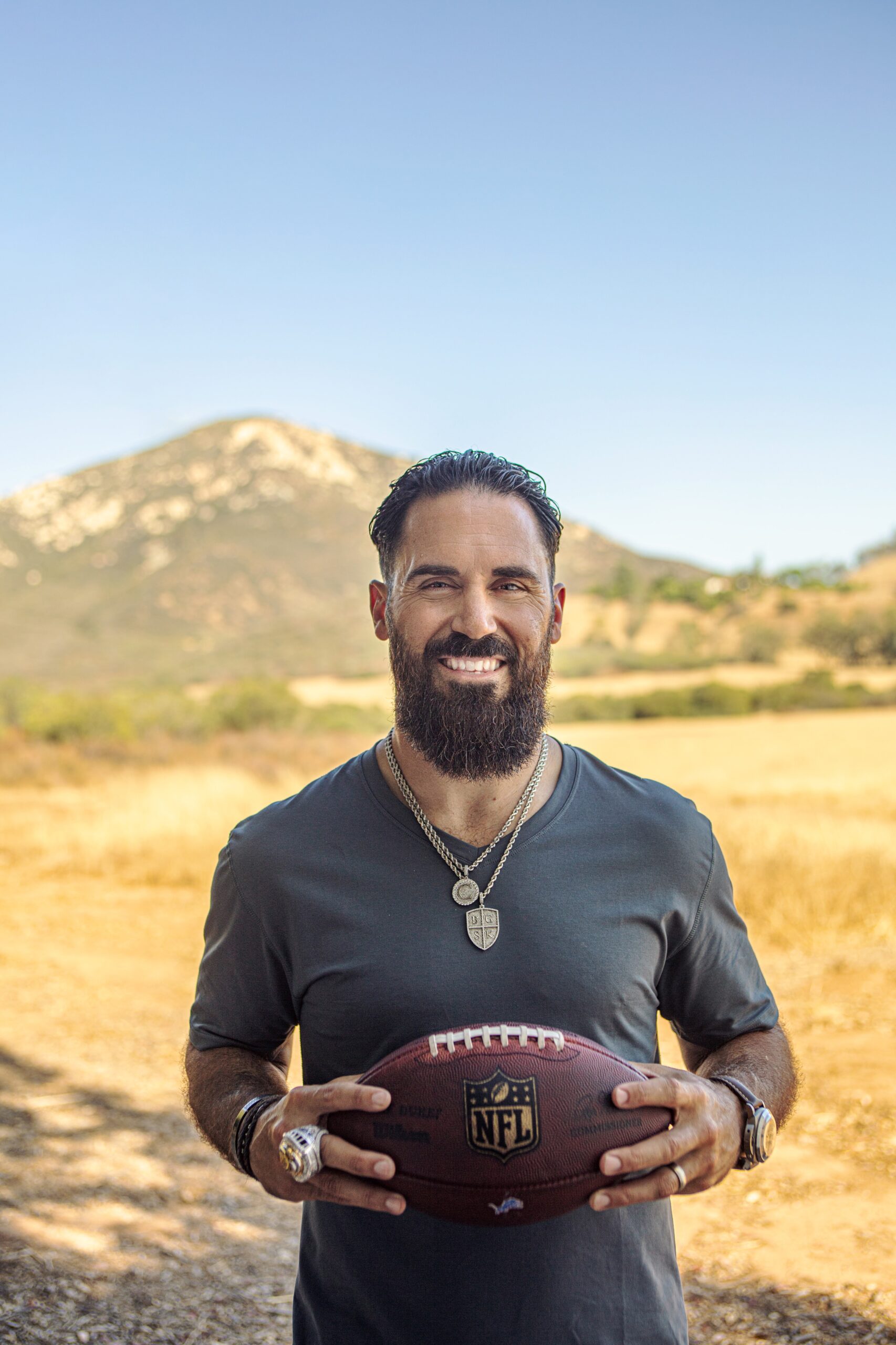

Just three weeks before Super Bowl LVI took place in February 2022, ex-NFL safety Eric Weddle got a phone call that sounded more like the neighborhood kids asking him to come out and play. And to some extent, it was.

Only it was the Los Angeles Rams, a little stunned themselves by their underdog status as an unlikely contender in the playoffs for the highly coveted Super Bowl. The California team found itself unexpectedly without either of its safeties, and so it turned to a former teammate, who had retired two years earlier after a 13-year-long career in the NFL.

“The first question they asked me, is what kind of shape I was in,” recalled Weddle. He admits he is still pinching himself, several months after helping to lead the Rams to victory.

The surprise invitation would create the ultimate in second chances and also turn Weddle into an even bigger role model off the field.

Redemption

Weddle, remembered mostly for his days with the Baltimore Ravens and San Diego Chargers, retired after the 2019 season with the LA Rams without a Super Bowl win—a reality that was tough for him, he said, but something he just had to accept.

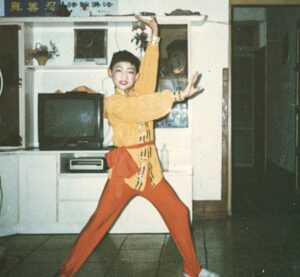

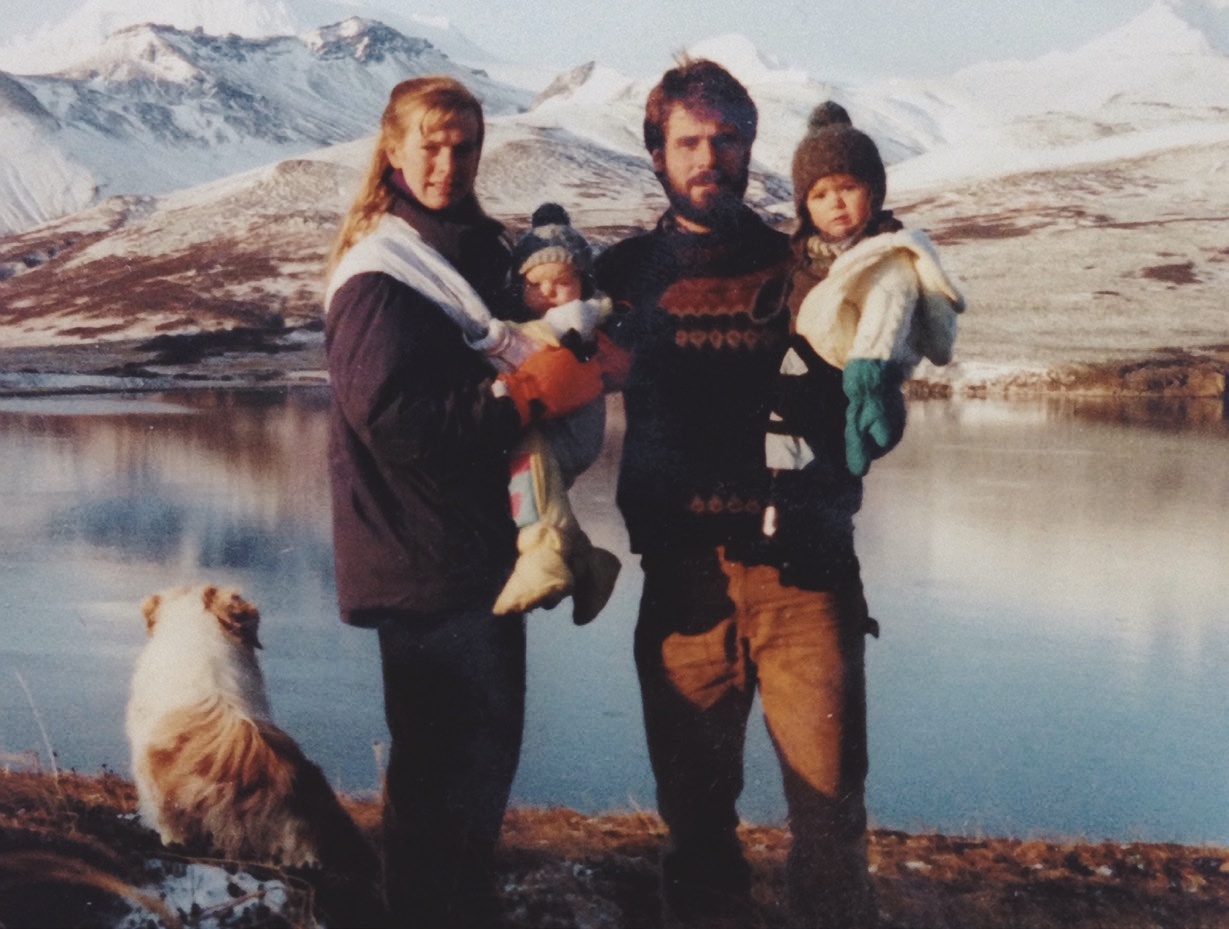

The six-time Pro Bowler and two-time All-Pro player thus settled into life as a full-time dad. Weddle soon became busy making school lunches and driving around his son and three daughters to their litany of activities: Brooklyn, the eldest, plays volleyball and soccer; Gaige, obviously football; Kamri is involved in acrobatic dance; and then there’s Silver, whom Weddle affectionately calls “our baby monster” because she’s into everything!

Then came the phone call. After Weddle’s return was announced to the press, Rams coach Sean McVay expressed this laudatory sentiment: “If there was anybody that was going to be able to do it, it would be him.” Not only did 37-year-old Weddle suit up, but his performance was bar none, completing five tackles—with a ruptured pec to boot—in what turned out to be one extra-glorious win against the Cincinnati Bengals. His tackle of Bengals wide receiver Tyler Boyd during the team’s final drive deprived it of one more chance to add points to the scoreboard, leaving the Rams’ lead of 23–20 as the final score at the Super Bowl.

Weddle was the talk of the town with his storybook comeback, headlining ESPN, CBS Sports, and every other media outlet in between.

A ball-hawking safety who led the league in interceptions and was recently placed on the 2023 ballot for College Football Hall of Fame for his early days with the Utah Utes, Weddle was back in the game, and the NFL wanted him. Who wouldn’t cave to such temptation?

Football Lessons

But to Weddle, the choice was clear. This fall, Weddle hit the field as head coach of the Broncos—that is, the Rancho Bernardo High School Broncos in San Diego, a homespun venue far removed from the million dollar NFL clubhouses that Weddle is so well-acquainted with. It’s also where his 14-year-old son is now attending school.

“I had every opportunity, but in my mind, if I’m going to be involved in football, coach anyone, why not it be with my own son,” reflected Weddle—who, by the way, also loves to cook. “This is an opportunity for me too, to be a leader in a different way to my kids and the other kids.”

Leadership, he said, sometimes means not being afraid to go against the mainstream. And he sees football, as well as other sports, as an unsung teacher of leadership—both on and off the field. “You learn so much from sports, how to treat people, how to interact, how to work through problem solving, how to communicate, how to handle adversity, and competing,” he said. “You’re also trying to beat other people at a play. Sometimes it works in your favor and sometimes it doesn’t. Are you going to quit, or are you going to keep fighting and keep pushing?”

And if you’re not hooked on football yet, consider Weddle’s viewpoint on how it could mend the world through example. “Every football team has a great locker room,” he said. “Race, political views, where you’re from—that all doesn’t matter, because we’re there as a team with one common goal: to win.” This world, said Weddle, could unify, if people just started acting like a team.

Weddle is also a dedicated church leader. As a stake president in the Church of Latter Day Saints, he is actively involved in church fundraisers, youth camps, and coordinating speakers for the church’s radio fireside chats. During his NFL career, it was pretty common for Weddle to seek out a church near the stadium where the team was playing to attend service before the start of a game. His faith, he said, has kept him grounded and focused on what’s most important.

And right now, that is coaching the Rancho Bernardo Broncos to a championship, something Weddle talks as passionately about as his NFL career. With a pride-filled motto of “Blue In, Blue Out,” the blue-and-white-uniformed Broncos seem just tailored for Weddle. Already well-versed on the team’s stats, Weddle already has some game strategies in mind for his new team.

Of course, he might have a little extra inspiration on hand, or that is, on his hand: a big, shiny Super Bowl ring, for one shining star.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.