In the fall of 1962, a little airplane manufacturer on Long Island, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, beat out seven competitors for the lunar module contract. How did this happen?

The story begins when Leroy Grumman, the company’s founder, struck out on his own in 1929. Working out of a rented garage, he began developing some of his own experimental airplane designs. In 1932, he presented the U.S. Navy with the FF-1, his first production fighter aircraft. The plane’s design continued to be improved, leading eventually to the creation of the F4F Wildcat, Grumman’s first fighter with folding wings.

Grumman built tough planes. The “cat” series, built for the U.S. Navy, had a reputation for getting their crews home. The sturdy aircraft, designed and built for carrier deployment, earned the company the nickname “Grumman Iron Works.” Aluminum, however, was the material Grumman engineers had real mastery over, forming it into beautiful aerodynamic shapes to build their planes.

Enter Aeronautic Engineer Tom Kelly

Grumman engineer Tom Kelly spoke of his involvement in the early development of the moon lander: “I guess I’ve been involved in Apollo-related work as long as anybody in Grumman, actually. I started on the thing in 1960—April 1960.” Kelly and his team competed for NASA-funded studies. Though they didn’t win any of them, Kelly said, “we went down and gave our own study conclusions to the NASA people right along with everybody else—we had a very active interest in-house, and we just wouldn’t let it die; whether it was funded, or not, we kept going with it.” Kelly’s work ushered in a whole new era for the company.

Grumman was not one of the larger competitors for NASA contracts. They initially offered to be a subcontractor in General Electric’s bid to build the command module and service module. North American Aviation beat them out. NASA had originally intended for the command module and service module to land on the moon and take off directly from the lunar surface to return to Earth. That particular spacecraft configuration proved to be prohibitively massive. It would require a rocket larger than anything already developed just to get it into space. But an engineer at Langley Research Center, John Houbolt, suggested taking along a smaller spacecraft, just to land on the moon. It would then launch from the lunar surface and rejoin the command module, which would now remain in lunar orbit.

The lander would be discarded after the astronauts transferred back inside the command module, which alone would return to Earth. Rendezvous in lunar orbit seemed risky, but it saved so much weight that it allowed the program to go forward at a pace that would meet President John Kennedy’s challenge to land on the moon within the decade. When NASA decided that they would develop the program around the lunar-orbit rendezvous approach, Tom Kelly and his team were well prepared to offer their proposal. Grumman wrote up the proposal, and General Electric became the subcontractor for the lander’s electronics.

When they won the contract in 1962, Kelly and his engineering team realized that they would be faced with the same challenge that had faced Leonardo da Vinci, the Wright brothers, and Charles Lindbergh: weight! Every step forward in human flight had involved overcoming the limitations imposed by gravity. NASA gave them an initial estimate of 30,200 pounds for the spacecraft. The craft that landed on the moon and then launched from the lunar surface to rendezvous with the command module had to fit within this prescribed limitation. They had seven years.

Overcoming Challenges

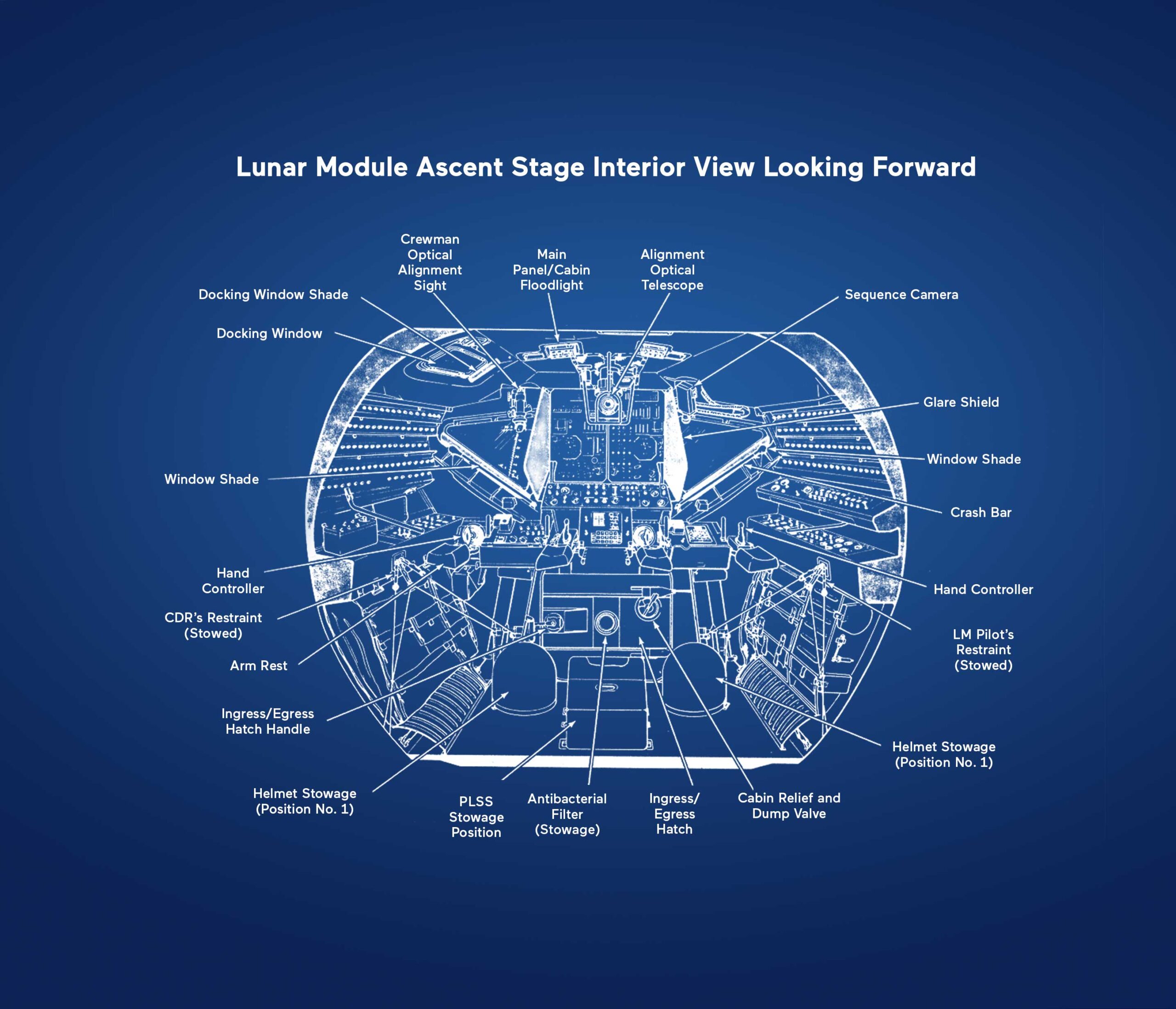

Kelly’s team worked tirelessly to conserve weight in unusual ways—in particular, the engineering of the astronauts’ seats. Grumman built 15 landers, 6 of which actually went to the moon. Some of the others are on display in museums, and visitors often ask where the astronauts’ seats are. In 1964, the design team eliminated them. The astronauts flew the lander standing up. In gravity that was one sixth that of Earth, the astronauts could fly, land, and take off standing in the craft. Their legs were all the shock absorbers they needed. With no seats, the astronauts also had more room for donning their space suits for the walk on the lunar surface. They could also hang their sleeping hammocks for the rest they needed while on the moon. Removing the seats saved weight in itself, but the move also allowed the astronauts to stand closer to the craft’s windows, allowing them to be significantly smaller. This saved hundreds of pounds of glass as well.

Astronaut Pete Conrad would refer to the cabin design as a “trolley car configuration.” Bethpage, New York, where the landers were built, is just 30 miles east of Brooklyn, where trolley car motormen actually stood up while operating a throttle with the left hand and a brake with the right. According to Kelly, those trolley cars had already inspired the name of a baseball team. Manhattan residents, who had more subways, sometimes referred to Brooklyn’s inhabitants as “trolley dodgers”; hence, the team’s name came to be the Brooklyn Dodgers. Did the trolleys of Brooklyn also influence the design of the lunar lander? Conrad’s reference suggests it might have.

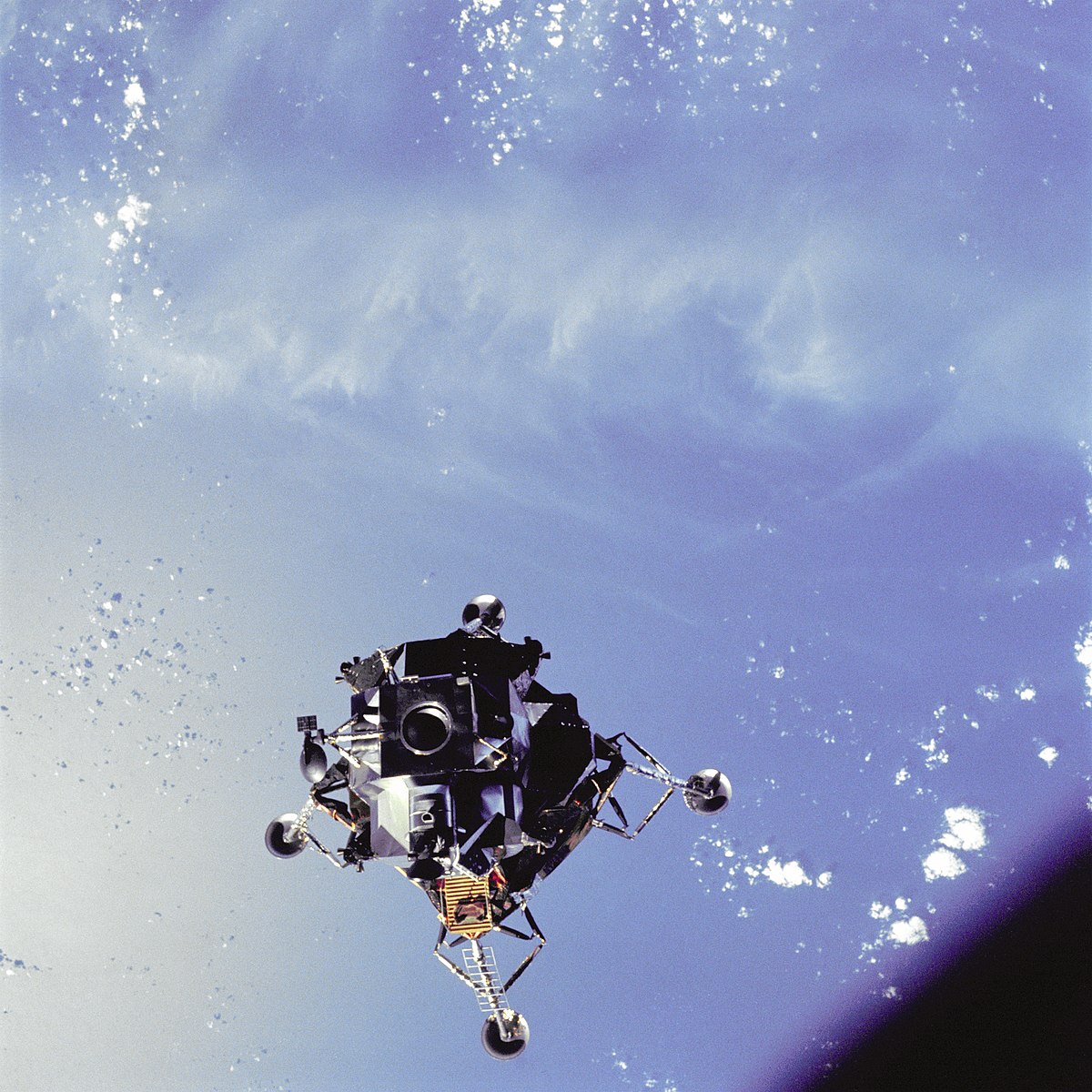

The landing module (LM) had to operate in extreme temperatures. The team came up with the Kapton sheeting (a kind of Mylar foil covered with gold leaf) that gives the lower part of the craft its “tinfoil” appearance. It simply reflected the solar heat away from the spacecraft, much like a windshield reflector does for a parked automobile. Because the lander never had to fly in atmosphere, it needed no aerodynamic design—no smooth, rounded surfaces to resist airflow. It could just be a long-legged, boxy shape. The first manned LM, flown in the Earth’s orbit by Apollo 9, would be called “Spider.” After one more dress rehearsal in lunar orbit by Apollo 10, the “Eagle,” flown by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on Apollo 11, would land on the moon. The date was July 20, 1969—eight years after John F. Kennedy laid down the challenge.

Tom Kelly and the Grumman team did some thinking beyond the task at hand that proved invaluable just two missions later. They recommended designing “lifeboat” capabilities into the LM. These capabilities would save the lives of the Apollo 13 astronauts when their command-service module was crippled by an explosion. The crew fired up the LM and used it to provide life support and navigation right up to the time that they jettisoned it. The command module was the only part of the spacecraft that could reenter the atmosphere. Though the LM “Aquarius” was consumed in a fiery reentry itself, the “Grumman Iron Works” team had successfully delivered one more crew safely home. In 1994, Grumman merged with the Northrup Corporation to become Northrup Grumman, one of the country’s largest aircraft manufacturers. In 1994, Grumman merged with the Northrup Corporation to become Northrup Grumman, one of the country’s largest aircraft manufacturers.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.