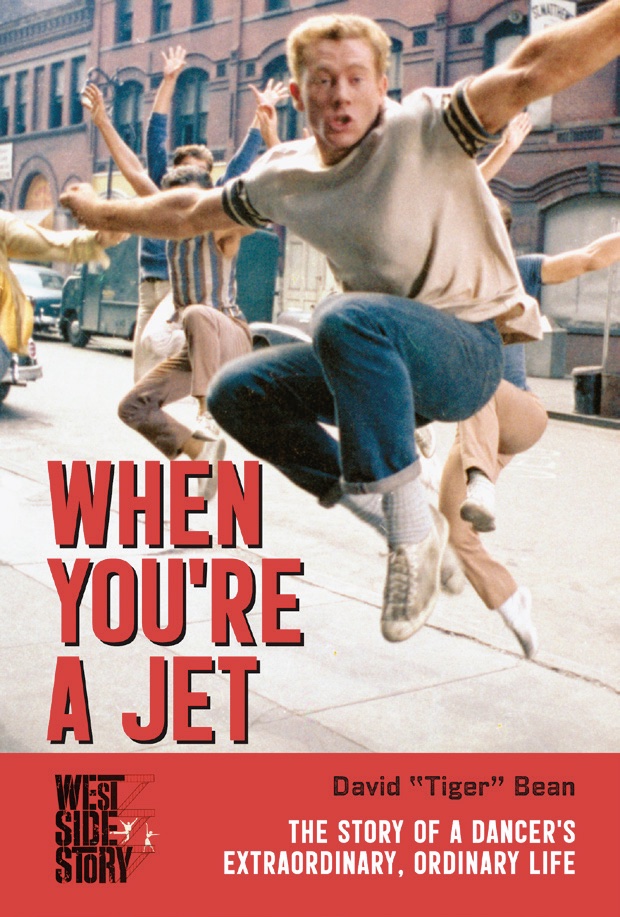

David Bean has been a teenage gangster, a lost boy, a farmer, and an author—the first two on stage and screen, the latter two in real life. Real life and the actor’s life flow together in his 2021 memoir, the subtitle of which is apt: “The Story of a Dancer’s Extraordinary, Ordinary Life.”

The title of his book, “When You’re a Jet,” gives away the gangster identity. Bean played Tiger, one of the Jets in the 1961 film of “West Side Story,” as well as other Jet roles in the London and British touring productions of the celebrated musical. As his biggest claim to fame, the movie role occupies the biggest chunk of the book. In an interview, Bean explained why he believes “West Side Story” was one of the most important musicals of the 20th century: “The genius of the men who created ‘West Side Story’ will never be equaled. The passion of Leonard Bernstein’s music, the passion that [choreographer] Jerry Robbins instilled in each of us to tell the story in dance, and the lyrics of Stephen Sondheim that were real and effortless to perform.”

Bean spoke from his home in Clifton Corners in upstate New York, where, at 83, he lives the placid life of a farmer, doubling as an assistant at his daughter’s place of business, the Jeanie Bean & Family Deli & Café. After the 1970’s and leaving show business, Bean and his wife explored a number of post-dance businesses, including real estate sales, art restoration, construction, picture framing, and, most prominently, farming and the restaurant business.

It’s an amazing contrast to the visceral, dynamic, peripatetic life of a Broadway and Hollywood dancer-actor that he led in his younger years. In those halcyon days, he met and rubbed shoulders with the likes of Marlon Brando, Marilyn Monroe, and Richard Nixon. Today, he supervises the frozen food selections at his daughter’s deli. The ordinary indeed meets the extraordinary in the life of David Bean.

Starting Out

“When You’re a Jet” is a time capsule of what it was like to work as a dancer in theater and film during the 1950s and ’60s. Bean entered that world as a 14-year-old when he won an audition to play one of the “Lost Boys” in the 1954 Broadway musical adaptation of “Peter Pan.” Its star was Broadway legend Mary Martin, but it was two men associated with “Peter Pan” who became important figures in Bean’s life. One was the choreographer Jerome “Jerry” Robbins, the other was actor Cyril Ritchard.

Robbins was one of the most important dance creators in Broadway history. As of 1954, his biggest credit was the choreography for Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “The King and I.” He had also choreographed ballets, including “Fancy Free,” to music by Leonard Bernstein. With “Peter Pan,” he entered the challenging arena of creating dances for characters who flew and whose numbers included seven young teenage boys. Bean came to admire Robbins as an exemplar of what he calls “the 180 rule”—an attitude that demands 180 percent from oneself. Bean explains in the book: “As a young boy, whenever Dad would offer me an important job, I would eagerly accept. … Before he would tell me what the job was, Dad would typically remind me, ‘Now this job is really important, and I know you’ll give me 100 percent.’”

Bean offered to give 125 percent, and his dad, nicknamed “Beanie,” would come back with 150 percent. Bean came back with “I’ll give you 180 percent!” and the number stuck. The “180 percent rule” became a lifelong motto for the younger Bean. “To this day, my wife Jean and I credit our ‘extraordinary, ordinary life’ in good measure to living out the 180 percent rule.”

Robbins demanded the same extreme dedication from his dancers. The choreographer was known throughout his life as a difficult taskmaster who could, when the occasion called for it, grow red with anger at incompetent performers. Bean saw only the positive side of Robbins, whose laugh he recalls was a “delightful giggle,” save one memorable incident. Bean had messed up a line in a dress rehearsal for an invited audience, and instead of letting it go had grimaced in self-deprecation in full view of the crowd. Bean recalled: “Jerry came backstage and I thought he was going to freakin’ kill me. He said, ‘If you ever do that again, I’m going to throw you in the pit.’” Needless to say, Bean never did that again.

Theater Adventures

Cyril Ritchard played Captain Hook in “Peter Pan” alongside Bean’s “Lost Boy” role, shaping that part into an iconic portrayal that captured the imagination of millions on stage and in two television broadcasts. Ritchard became a “theater father” to young Bean during the run of “Peter Pan,” establishing a lifelong friendship both with Bean and his family. While “Peter Pan” was on Broadway, 1954 and 1955, Ritchard hired the elder Bean as his backstage dresser—the man responsible before each show for making Captain Hook look lovably scary.

“Cyril became my theater father,” Bean said. An Australian actor born to wealth, Ritchard projected a breezily aristocratic air, contrasted with Bean’s all-American brashness. But they had something deeper in common, albeit expressed differently: Ritchard boasted the Latin motto, “Optimum Semper,” translated as “Only the Best,” an echo of Bean’s “180 percent.”

When Ritchard’s wife died in August 1955, the actor decided to leave New York for Los Angeles. By that time, “Peter Pan” had closed, and Bean had relocated back to California. Ritchard opted to drive from New York to LA in his 1941 Chrysler but didn’t wish to do so alone. So Bean, now 16, flew to New York to join his theatrical father in the coast-to-coast drive. Therein lies one of the funniest stories in Bean’s book.

Most of the drive was uneventful. Somehow, they found a Catholic church every morning in order that Ritchard, a daily communicant in the Catholic faith, could attend mass. Then, somewhere west of Phoenix, a tire blew. No big deal at first. Ritchard had had the spare checked out before hitting the road and Bean was, like his (non-theatrical) dad, a natural mechanic.

“Mechanically I’m pretty good, so when that tire blew, I had the car jacked up and the tire off in about 10 minutes,” Bean recalls. But when he pulled the spare from the trunk, Bean found that one of the lug nuts securing the spare had been tightened with a pneumatic wrench.

“I tried and tried with the tire iron, but it was clear that lug nut wasn’t coming off manually.” Bean left Ritchard in the car and hitched to the nearest town to hire a mechanic to drive him back with what should have been a truck full of tools—except that the mechanic forgot to bring his tool box. Quoting from Bean’s book:

“In the front seat of his truck, he found a hammer and chisel. ‘I can knock those nuts off with the chisel and you’ll be off and running.’ He climbed into the trunk with his hammer and chisel. Placing the chisel behind the base of the lug nut, he swung his hammer as hard as he could. The hammer hit the tire and bounced back like a shot, hitting our rescuer in the forehead, knocking him out cold! There we were, in the middle of the desert with a disabled vehicle on the side of the road and a disabled mechanic out cold in our trunk.”

After a tense interval, the mechanic came to. Ritchard had until now sat gallantly in the car, sweating in the 105-degree heat but with his iconic cravat still around his neck. In an act of genuine image-sacrifice, Ritchard removed the cravat to help staunch the mechanic’s bleeding. At length, the plan was launched to pile into the mechanic’s truck and drive back to his garage, spend the night at a motel, and then head back to the Chrysler with a completely new spare. Such were the ordinary trials of an extraordinary life.

While Bean was finishing high school in California, his old boss Jerry Robbins was creating a masterpiece in New York. “West Side Story,” conceived and choreographed by Robbins as a contemporary take on “Romeo and Juliet,” opened in 1957 and sent shock waves through the theater world. Here was a musical that addressed gang violence and ethnic division while radiating hope through athletic dance and a soaring score of songs such as “Somewhere” and “Maria.” When a London production was announced, Bean auditioned and was cast as one of the “Jets,” the Anglo rival gang to the Puerto Rican “Sharks.” Thus began several years of being a Jet, as Bean was cast as “Big Deal” in the London production in 1958, as “Tiger” in the Oscar-winning 1961 film, and as “Action” in the British tour of the early ’60s. In the film, Bean can be seen threatening the Bernardo character with his fist in the Prologue and pretending to be Officer Krupke while the other Jets sing to him in “Gee, Officer Krupke.”

Loving Life

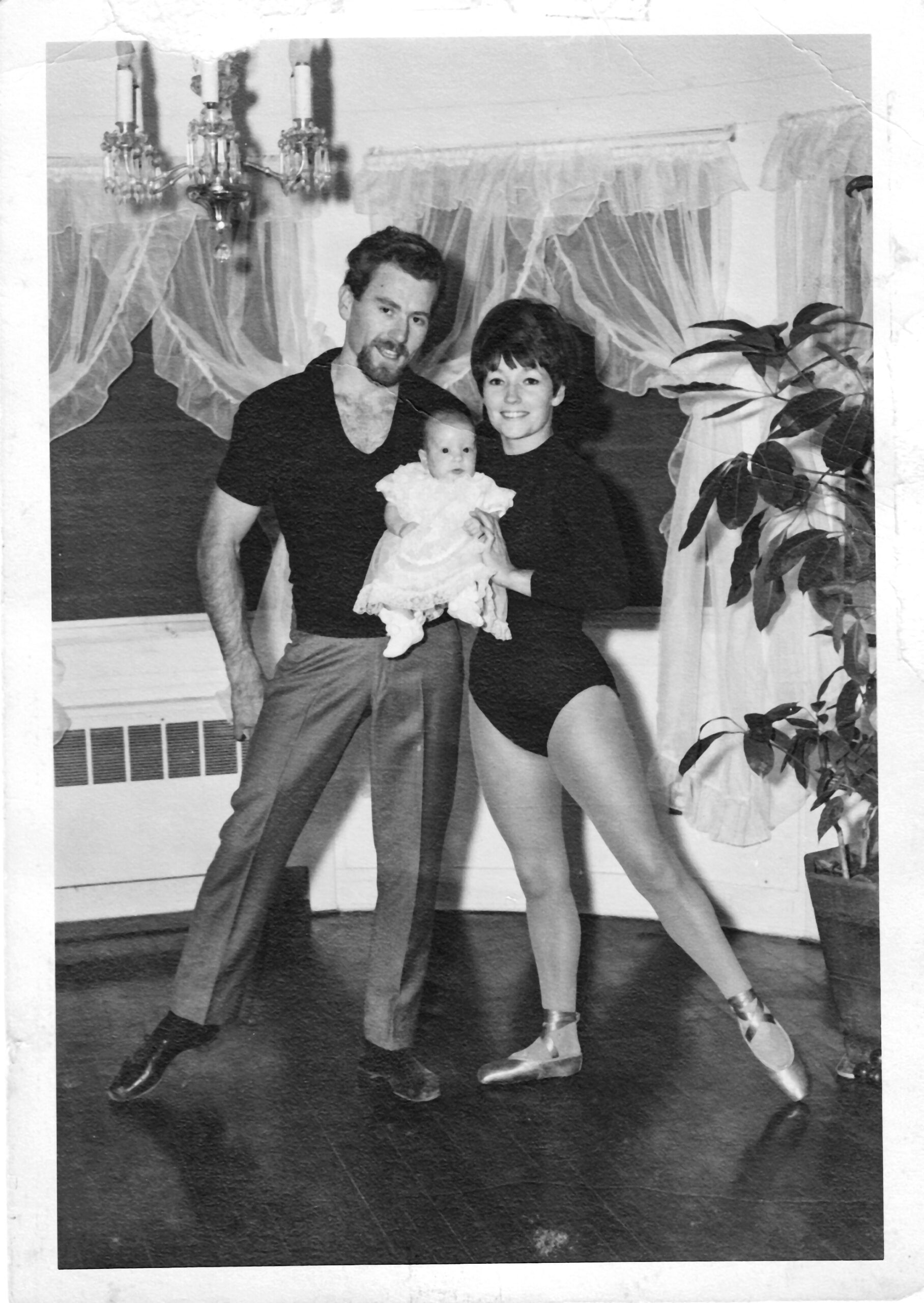

During the London production, Bean met his match: a slender young English dancer named Jean. They enjoyed what Hollywood calls “a cute meet.”

“We danced opposite each other in the ‘Dance at the Gym,’ and she made a wrong move, causing me to twist my ankle. I didn’t talk to her for six weeks.”

When six weeks were up, the romance began. Almost as soon as it started, Bean was called back to America to perform in the film. Their love survived a year of long-distance, and they went on to become a married couple and the parents of a daughter, Jennifer.

During the London run, Bean also made a lifelong friend in George Chakiris, who would go on to win an Oscar for his portrayal of Bernardo in the movie. In London, however, Chakiris played one of the Jets. This had made it possible for him and Bean to become friends. If one of them had been a Shark, it wouldn’t have happened, for Robbins imposed a strict rule that kept Jets and Sharks from seeing each other socially. He was serious about it and promised that any Jet who palled around with a Shark (or vice-versa) would be fined. It was part of Robbins’s method-acting approach to creating emotional tension between the gangs. That didn’t affect Chakiris and Bean in London, but when Chakiris was cast as head Shark Bernardo in the movie, it meant that these two good friends had to stay apart.

One day Chakiris phoned Bean and said, “You have to come over and have spaghetti with me and Rita Moreno (who was playing Bernardo’s girl Anita) and her boyfriend.” After weighing the odds of getting caught fraternizing with “the enemy,” Bean showed up for the spaghetti, and he met Moreno’s boyfriend, an actor by the name of Marlon Brando. (He wasn’t caught.)

Bean’s association with “West Side Story” didn’t stop with the British tour. In 2019, Steven Spielberg invited him to make a cameo appearance in Spielberg’s remake. Bean can be seen in one of the storefronts during the “America” number.

Bean wrote his book to savor the past and speak to the future. “The values we were brought up with by our parents were gold. It was a golden time,” he said. And to today’s young, he advised: “If you have a passion for something and you put 180 percent into that passion, I guarantee your success.”

From Sept. Issue, Volume 3