Truesdale Marshall, in Henry Blake Fuller’s 1895 novel, “With the Procession,” had this to say about Chicago: A “hideous monster, a piteous, floundering monster too. It almost called for tears. Nowhere a more tireless activity, yet nowhere a result so pitifully grotesque, gruesome, appalling.” This was the assessment of the great city that had risen so rapidly in the plains of America’s Midwest. The young nation had barely survived its civil war just decades before. Chicago was still recovering from its great fire. Railroads rushed to cross and crisscross the fruited plain, building quickly. There was no time for building beautiful arched bridges. Wooden trestles were thrown up in a matter of weeks. Track was measured in miles laid per day. “Hell on Wheels” was the order of the day. Midwestern cities were ugly, smelly, and chaotic.

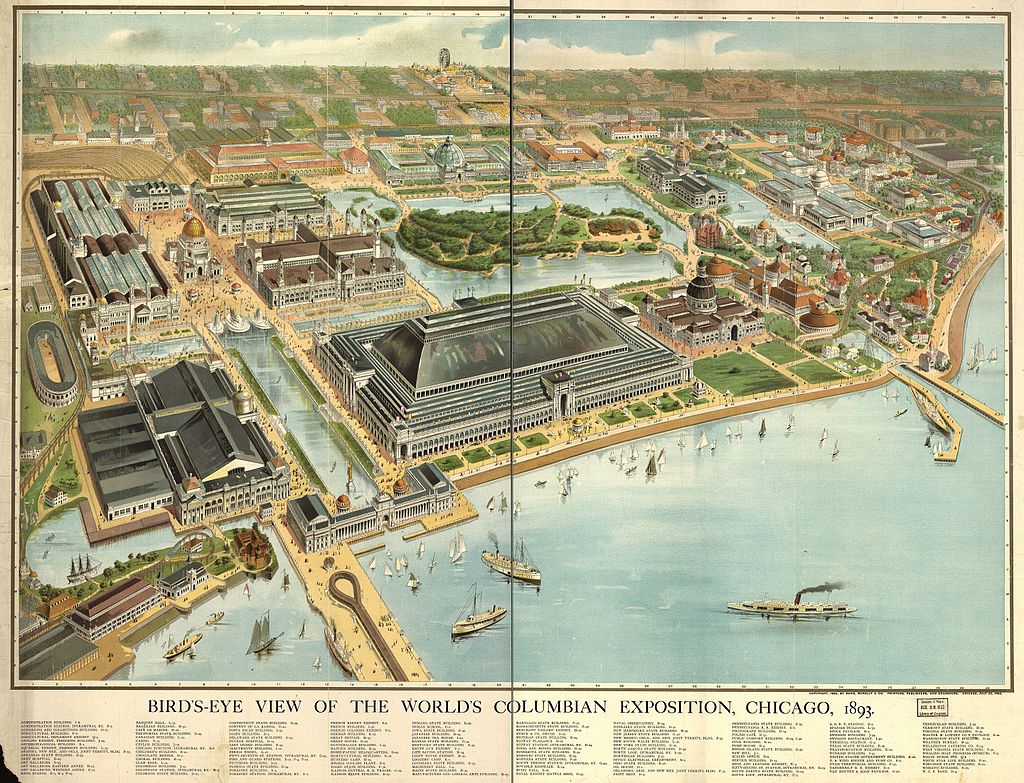

But then, in the summer of 1893, a gleaming city appeared on the shores of Lake Michigan, something that didn’t seem to belong to this boisterous time. It only stood for a brief season, but it would change the course of a nation’s development. Massive Classical buildings rose majestically above a series of great lagoons. Beauty rose from the chaos of unbridled growth as a swamp along the shore of Lake Michigan became the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition—the Chicago World’s Fair.

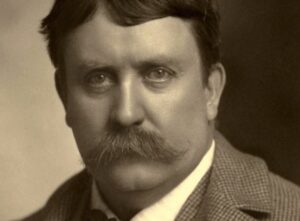

It was inspired by the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris and was conceived to honor the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America. Chicago had beat out established cities like New York and now set to work to build a great international fair in the heartland of America. Daniel Hudson Burnham, of Burnham and Root, was selected as Director of Works for the fair. He was an accomplished architect and urban planner and a strong advocate of the Beaux-Arts movement. He would go on to design the magnificent Union Station of Washington, D.C. Now, he had a fair to create.

Enlisting some of the finest minds in architecture, Burnham struggled to create a unique site for his fair. Frederick Law Olmsted, the great landscape designer, envisioned a series of lagoons and canals, creating a modern-day Venice. The signature building of the fair, the Administration Building, was awarded to Richard Morris Hunt, a fine Beaux-Arts architect who had designed the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Hunt had done numerous commissions for the Vanderbilt family, including working with Frederick Law Olmsted to create Biltmore Estate, the largest private home in America.

Hunt’s rendered elevation for the Administration Building is a beautiful watercolor in the finest Beaux-Arts manner, rich in layers of Classical detail. Burnham, Hunt, and Olmsted clearly laid forth a vision for something timeless, a vision of what a city should be, but time was of the essence. An entire city would have to be built in less than two years. It would already open a year late for the 400th anniversary celebration. It was also temporary. The fair would only operate for six months and then be torn down, so the builders did not use carved stone at all. Instead, they built an enormous stage set! The large buildings of the Court of Honor were hastily built on steel and wood frameworks that were covered with lath and a fibrous plaster-cement mixture called “staff.” Details were molded out of plaster.

Each building would need to be painted to protect it from the elements. Brushing would take too much time, so the builders developed an efficient method of spray-painting everything white. The result was a series of huge buildings that were bright in the summer sun. The press dubbed it the “White City.” Black-and-white photographs of the fair add to this impression. Though George Westinghouse’s electric illumination of the fair included colored lights, the impression guests received by day, and that of newspaper readers, was monochromatic. The technology that would propel America into the 20th century was proudly displayed on a Neoclassical stage. Over 27 million visitors would come to the fair.

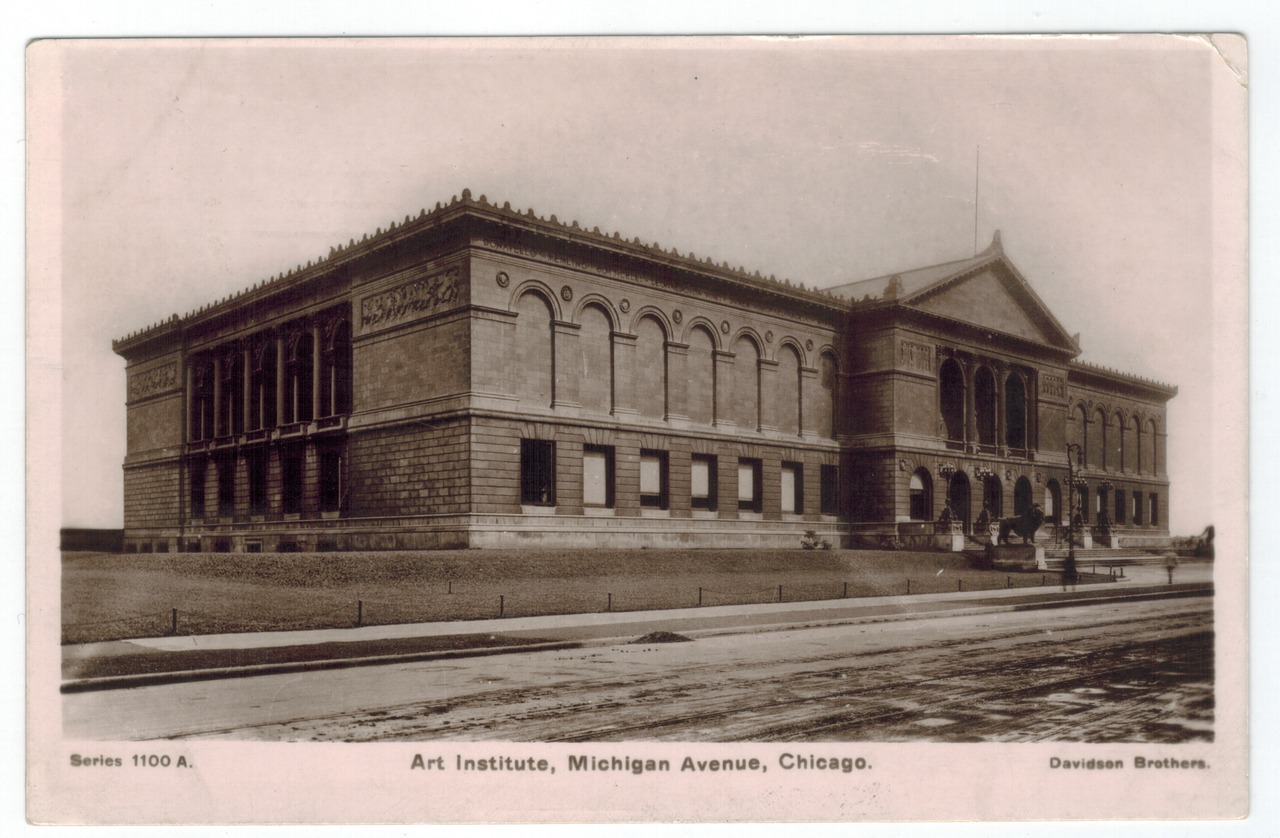

There were some who wished that the fair’s Classical architecture could be preserved, but that was not possible. The staff-covered buildings were simply not durable enough. They were also firetraps. During the fair, the innovative Cold Storage Building had burned to the ground, claiming 17 lives. The Peristyle, a massive colonnade facing Lake Michigan, burned down right after the fair, killing two more people. Only the Palace of Fine Arts, built more substantially to meet insurance requirements for the artwork displayed there, would survive. Today, it houses the Field Museum, but it has been substantially rebuilt. The World Congress Building, built just outside the fairgrounds, remains today and houses the Art Institute of Chicago. It was built for the fair but was not actually an exhibition building. The Pabst (beer) Pavilion, the Pavilion of Norway, and a few state pavilions were moved elsewhere.

The Beaux-Arts Classicism the fair inspired would endure, however, as a series of international expositions continuing into the early 20th century and built in the same theme. San Francisco, Atlanta, Nashville, Omaha, Buffalo, Charleston, St. Louis, Portland, Seattle, and even little Jamestown, Virginia, would host fairs. The resurgence of Classicism would inspire many important civic buildings and institutions, ushering in a new wave of American architecture. But already, there was a disagreement over the future of America’s public architecture. Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building at the 1893 fair was a substantial departure from Classical forms. Sullivan and his apprentice, Frank Lloyd Wright, would seek to create a distinctive American architecture apart from European Classical forms. Wright’s work would find inspiration in the Chicago fair’s Japanese Pavilion.

Daniel Burnham went on to lay out new urban planning for Chicago and would go on to serve with Charles McKim (of McKim, Mead, and White), Fredrick Law Olmsted, and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in creating the 1901 McMillan Plan to redesign the monumental core of Washington, D.C. The plan would define the National Mall we know today, a great avenue and green-space flanked by classical museums. In smaller cities and towns across the nation, Neoclassical courthouses and banks would also rise to underscore a new sense of national identity.

Bob Kirchman is an architectural illustrator who lives in Augusta County, Virginia, with his wife, Pam. He teaches studio art (with a good deal of art history thrown in) to students in the Augusta Christian Educators Homeschool Coop. Kirchman is an avid hiker and loves exploring the hidden wonders of the Blue Ridge Mountains.