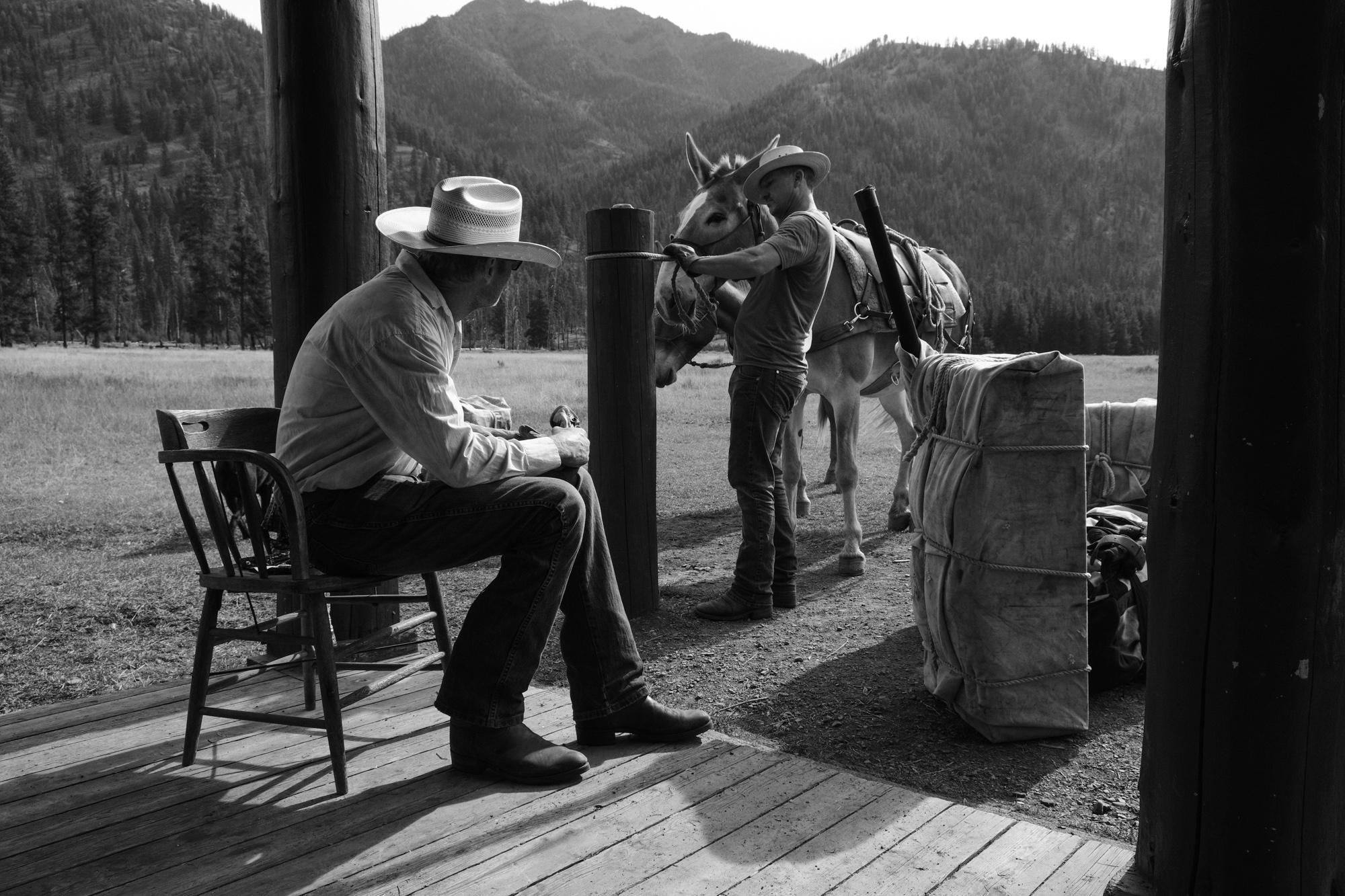

Out in the roughly 112 million acres of land that are designated as “wilderness areas” by the federal Wilderness Act of 1964, no motorized vehicles or “mechanical transport” are allowed to operate—not even a wheelbarrow. That’s where mule packer Chris Eyer comes in. Together with his pack of 10 to 15 hardworking animals, he helps to transport supplies for the U.S. Forest Service and outdoor guides who bring people out on wilderness trips. It was a lifelong dream: When he was about 14, he went on a mountaineering school trip to the Sierras in California, and he spotted a man with a pack of mules. That moment was seared into his mind and sparked a desire to one day embrace the Wild West archetype.

Along the way, Eyer served in the Marine Corps during the first Gulf War (“I had a strong sense of garden variety patriotism and a real love for freedom”), went to university, started an electrical contracting company, and began crafting saddles. The mule packing is mostly a volunteering endeavor born out of the love for the outdoors. He lives in a pocket of wilderness in Ovando, Montana, nestled in the northern Rocky Mountains, known as the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex (“I live in a spot where I can ride out my front door and go all the way to Canada”). Today, he sits on the board of directors for a foundation that maintains the wilderness complex and runs programs that bring people to explore the area.

Eyer spoke to American Essence about what mule packing entails and the deeper meaning behind connecting with nature.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

American Essence: What is a typical day like for you?

Chris Eyer: I would wake up at 5 a.m. I would have all of my loads already made. So everything would be all put together and wrapped up in what we call manties [tarps]. I make coffee and start to wrangle all my stocks, get them loaded up into the trailer, and I’d head to the trailhead. I drive up there, unload, and then I go through a process of brushing everyone, making sure everyone is sound and looking good, put pads on them, saddle them all, get them all ready to go. I take these heavy loads, which are usually about 75 to 90 pounds per side, so anywhere from 150 to 180 pounds per animal, which for them is really not heavy. We always keep it to less than 20 percent of their body weight. If everything goes really smoothly, I’ll be on the trail by 9 a.m. A typical day for me would be riding anywhere from 18 to 25 miles, at which point I would stop and drop all the loads. And then I would take all the saddles off. Then I would start the process of turning my stock loose for the night, so that they can graze and water all night unimpeded. I’m normally in bed asleep by 8:15. And then I wake up in the morning and do it all again, whether I come out empty or move heavy things to the next destination.

American Essence: Why do you do what you do?

Mr. Eyer: For most people who take part in this wilderness area, they’re highly transformative [experiences]. Facilitating that is something I’m really interested in. Being back in a place where you are no longer on the top of the food chain, you’re traveling through areas full of grizzly bears and wolves and all sorts of different hazards—that’s actually an experience that’s more accurate to who we are as humans. Staying warm, staying hydrated, being fed, doing some work—that’s actually a very root experience for humanity. And I think it’s something that in this world we currently live in, where we’re just absolutely laden with technology, and we have all this information at our fingertips—to be able to come off the top of the food chain, to be able to go into our public lands, that’s just a really important salve for the postmodern mind. It’s allowing yourself to take part in the moment-to-moment change that’s happening around you, and not in a way that’s resisting it.

American Essence: What are the dramatic transformations you’ve seen in people?

Mr. Eyer: When you can watch people, especially people who are newer to the wilderness, develop a new relationship with themselves, and in particular, develop a new relationship with what it means to be afraid. We all have certain kinds of fears and anxieties: It might be about your job. It might be about your children, your future, your past, whatever it may be. But when you get down to the root of that emotion—which is easier to do when you are in the wilderness—you realize that all these different fears that you experience on a day-to-day basis are actually masks.

When you really are able to let go, you see yourself nested in a system, an ecosystem of relationships of which you are a part. In other words, you’re not back there dominating, or taking control of the wilderness, you’re actually taking part in the wilderness. You’ll begin to see that if it’s true that you are nested in a web of relationships, that to act any other way but compassionately towards all of the life that we’re surrounded by—would just be to act self-destructively.

Many people return [home] and talk about how they engage with work differently, they engage with their family differently, they see things for what’s really important: sustenance, but also community, connection, and being able to rely on individuals in the communities we’re involved in, wherever that might be.

American Essence: What’s the most hairy situation you’ve been in while mule packing?

Mr. Eyer: I can remember a pack trip I went on where I was leaving camp, it was in October, and there was a light snow. And earlier that morning, we’d seen one of the largest grizzly bears I’ve ever seen, he skirted the boundaries of our camp. And then a couple hours later, when we were leaving, he popped out of these willow bushes and spooked the whole pack string, and the whole pack string took off at a full gallop. I ended up holding my horse, but off of him, about 10 to 15 feet away from this giant grizzly bear, face to face. Thankfully, he wandered into camp, and was interested in exploring whether or not we’ve left any food behind and was not interested in attacking me. There’s just countless stories like that.

From April Issue, Volume 3